•#1a: Film Series: Program Questions in Scenes

“Climb Up the Family Tree and Eat Some Fruits”

This week I watched “RADICCHIO WEEK: Davide Zimolo + his Nonna, Cooking Demo,” a recording of a live streamed event released as a part of the Culinary Breeding Network’s Winter Vegetable Sagra on Dec 8, 2020. I titled my scene “Climb Up the Family Tree and Eat Some Fruits” (10:46 – 16:39) to explore the program questions: “How can terroir/meroir best be understood, represented, shared?” What disciplines, practices or media are needed and why for knowing and communicating aspects of terroir/meroir?,” and “Where and how do people raise the foods we are highlighting, what factors influence the quality of these foods, especially their flavor?, and how are these foods processed, transformed and stored from farm to table?” I will call attention to the intimacy of the interview between grandparents and grandchild and the theme of generational knowledge, which is at the heart of terroir. Additionally, I will mention Nonna and Nonno’s obvious pride in being from farming families and how their traditional foodways are intimately tied to the agricultural, seasonal, and cultural knowledge they possess. I will also discuss their seeming mix of joy and anguish when discussing their childhood food memories, punctuated by the repeated mention of hunger.

My scene begins in the home of Davide Zimolo’s grandparents, as he sets out to cook two simple traditional dishes utilizing the traditional winter vegetable radicchio. Luigina Prataviera and Guido Mazzolin, Nonna and Nonno respectively, are seated in their simple, white kitchen at a small table adorned only with a needlework tablecloth. After encouraging his grandparents to introduce themselves, Davide begins his interview with a deceptively simple question: “Both of you are from farming families, right?” Nonno responds, “Both farmers, and proud to have been farmers.”

Nonna goes on to discuss growing up on a farm in Veneto, her parents’ labors and what they grew; she mentions of her family’s land, tractor, and barn, along with a story about cows pulling tanks of copper spray her mother would use to treat their vineyards, presenting a picture of agriculture with limited mechanization and heavy animal integration. She goes on to list all the agricultural products they raised: six cows for milk and cheese, pigs for sausages and cured meats, chickens, rabbits, corn, vineyards, and a large garden featuring a variety of vegetables, notably brassicas and radicchio; she specifically remembers her family eating two types of radicchio, one small and eaten with the roots and one larger and lighter which was used for salads. Nonno interrupts here, driving home a point of wisdom, “Radicchio was never missing from a winter garden.”

Davide then asks his grandparents, “What did you eat when you were kids?” His grandfather jokes that they were given plain bread with nothing on it. Nonna describes a slightly more believable diet, heavy on dishes like bean soup and pasta with chicken livers, along with garden greens, foraged fruits, and carefully preserved meats and cheeses: classic cucina povera. She fondly reminisces about the sausages and cured meats her father made himself: cotechini, blood sausages, salami, and figadei, a liver-sausage which is no longer common. She goes on to describe taking their cows’ milk to the local dairy and coming home with eight or ten blocks of cheese which would be kept and used throughout the entire year. “That’s what we ate in Veneto, those were our traditions.” Nonno recalls being hungry after meals growing up and being told to forage for fruits: “When we were done eating lunch, the grandma would tell us to climb up the fig tree and eat some fruits.” Nonna adds, “Because the kids were still hungry.” She jokes that they had better start preparing the risotto if they plan to have lunch, and as the butter melts in preparation for the risotto dish, Nonna prepares coffee. Holding small cups of espresso, Davide and his grandparents continue discussing the finer points of a good bean soup.

Nonna describes using scorseghe or “scors,” a piece of pig’s skin with no fat and the hair removed, to create a flavorful broth. Nonno face twists in a half smile, half grimace. “I always had to eat the scors; my grandma would leave it for me. When we came home from school, we were hungry. The other kids would get a slice of cotechino, and I got the scors, but it still had the hair and I had to remove it before eating. It was hard to remove it, but since it boiled in the soup it was much easier.” Nonna leans over conspiratorially, grinning from ear to ear, and says, “Sometimes I would go and steal a piece of salami from the cellar. I was crazy about them. They used to hang the salami up on a pole in the cellar. I would take a chair so I could reach them and take a piece. We were supposed to save the salami for the whole year, but I would go and steal them anyway. I was hungry!”

As Nonna and Nonno discuss their traditional foodways, pieces of knowledge concerning their production is also passed along. A discussion of farm-raised pigs not only results in a mouthwatering list of pork preparations, but also discussions surrounding husbandry, slaughter, processing, preservation, and storage as well. Seasonality and food preservation are linked directly to memories of their childhood meals; growing radicchio in the winter garden, the fall harvest and the slaughter of pigs, and spring cheese making are each discussed in turn, as well as the yearlong preservation and storage of many different foods in cellars. For Nonna and Nonno, eating and preparing traditional foods is meshed with the regional agricultural and cultural knowledge they began learning as children from their own parents and grandparents; that generational knowledge is the lifeblood of regional terroir, and by propagating Veneto’s traditional foodways as well as practicing them, Nonna and Nonno are keeping alive the lessons of their ancestors and creating a link to those lessons for their descendants (and me).

Though the foods they describe sound rich and flavorful, Nonna and Nonno also admit that they were often hungry as children. Whether caused by lack of abundance or the growth spurts of growing bodies, they mention three times the hunger they felt growing up. The “cure” for hunger prescribed by Nonno’s Nonna was to forage the land, telling her grandchildren to “climb up the fig tree and eat some fruits.” She was encouraging them to learn, live, and trust their regional terroir to sustain them; after teaching which fruits could be eaten, she insisted they put it to practice, guaranteeing that they could feed themselves independently if necessary.

Davide’s two simple questions inspired some extraordinarily complex answers. I appreciated the generational aspect of the conversation especially, in which the knowledge, skills, and habits of Davide’s grandparent’s grandparents are being passed to him in a five-link-long generational chain, a family tree which he might climb and find fruits. I found the interview particularly effective because, as a viewer, I was drawn into this family’s history along with Davide; through their memories, reminiscences, and stories, I was being included in an exchange of generational knowledge. And, like being passed a secret family recipe, generational knowledge of terroir comes with the implied dual imperatives to protect and preserve the information for future generations: a pleasure, responsibility, and burden. I’ll share how this scene compelled my learning surrounding the traditional seasonal foodways of Veneto in order for my audience to better understand the role of generational knowledge in relation to cultural terroir.

•#1b: (un)Natural Histories

Image by Sarah Dyer.

Image by Sarah Dyer.

Where are chicories native? What environmental conditions are ideal for growing chicories? When should you plant chicories to get the hoped-for-harvest? How are new varieties developed? How are seed varieties maintained to keep the variety looking and tasting the same?

Chicory, or Cichorium intybus, is native to Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia and was introduced to the US in the late 19th century. Italy, Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands cultivate chicory extensively, though interest in the united states is on the rise. Chicories exist in four basic forms: root chicory, forage chicory, forced chicory, and leaf chicory. The cultivation of radicchio, or red chicory, dates to the first half of the 16th century in the Venetian territories of Northeast Italy. After spreading to nearby territories, the original types differentiated into well-defined biotypes.

Commercial seed is mainly utilized outside the typical area of origin, and many commercial varieties are open pollinated populations derived through selection from the original genetic pool. Both synthetic and hybrid varieties have been put on the market and have been favorably adopted largely for out-of-season production. When saving seeds from radicchio, on must be aware of cross-pollination, which can lead to a wild mix of varieties (not necessarily a bad thing, but not great if you want to keep traditional characteristics intact. In Italy, on farm seed saving is normal. Because radicchio is open-pollinated, cultivating varieties is always about corralling plants to cross the way you want them to. Constant varietal maintenance and selection is required based on environmental constraints.

To produce blanched heads on Belgian endive, dig the roots out before a hard freeze. Cut off the tops about two inches above the crown, or top, of the root; store the roots in a cool place. In winter, force the roots in a cool, dark room by planting them in moist sand. Keep the emerging shoots covered with seven or eight inches of sawdust and water the plant occasionally. In three to four weeks, when new shoots emerge, cut the heads from the root. An easier and less expensive way to blanch the heads is to harvest by hand. Break or cut the heads just above the root, wash and trim them, and pack them into lightproof cardboard boxes. They must not be exposed to light, except for short periods, as even a small amount causes the outer leaves to turn yellow or green, making them bitter and impairing their quality. There are three ways to force radicchio to form a head: (1) cut the leaves off to within 1 inch of the crown 2 to 3 weeks before the first frost, and then dig the roots an store them in a burlap bag in a cool dark place (45 degrees to 55 degrees F) where they will produce a second growth of pale red heads; (2) leave the plants in the ground and cover them with straw or another mulch; or (3) leave the plants in the ground and let the frost kill the outer green leaves. Peel back the dead outer leaves and you will find the red head inside.

•#1c: Regenerative Agriculture

Why are chicories a good choice for diversifying winter vegetable production in the PNW? What soil and water conditions are well suited to growing chicories, paying special attention to our patterns of winter precipitation, shade, and frost? How can you time seasonal production to impact flavor, such as frost and sweetness? What pest and disease issues should chicory growers be aware of, and how might we manage when and how we grow chicories to minimize the buildup of pests and diseases?

The PNW mirrors the climate of Veneto, Italy, which is the native area for radicchio, in that it is rather cool and damp. Soil coverage = soil health! Winter chicories help keep soil covered during a season when many things won’t grow. One should be aware of coverage options after harvesting chicories, as a winter crop harvest can leave holes in your plantings. It’s important to consider cover crops and interplantings for winter chicories, and a farmer should consider establishing a good rotation scheme for chicories, interplantings and cover crops. Intercropping winter cruciferous vegetables or brassicas or broadcast planting clover and winter legumes could be useful. Keeping soil covered and productive during the rainy season can save the topsoil. Radicchios reduce the monoculture of PNW brassicas, “breaking the green bridge” (monocultures can lead to pests and disease in brassica crops). Radicchio and chicories have added value because (1) they give farmers another winter crop and therefore income stream and (2) because they are unusual and add color to otherwise dull winter brassicas. Radicchios are hearty and can be stored for some period, extending the farmers ability to sell the crop.

Chicory is a cool season crop and is best grown in fall and winter in warm winter regions and in spring and early summer for cold winter regions. Chicory likes temperatures between 45 and 75 degrees. It is best planted in fertile and well drained soils that are rich in organic matter, and in the full sun. It is suggested that growers apply organic mulches such as grass clippings, straw, and newspapers to help cool the soil during high temperatures, reduce water stress, and control weeds which will out-compete radicchio plantings and must be controlled. Chicories should be cultivated shallowly to avoid root damage and ensure uninterrupted plant growth. It must be planted so that it is established before too much rain or frost arrives (to accomplish this one might have to remove a summer crop.) It prefers soils with a pH of 6.5 to 7.2. It is best to keep the plants moist to prevent the development of bitterness, chicory usually requires 1 to 2 inches of water per week depending on the climate and soil growing conditions (in the PNW, that could be 1” or less). Chicory seeds’ ideal germination temperature (60-75°F) is well suited to early fall planting in the PNW, and the maturity date coincidences well with the typical first frost in our region typically occurring in late October. For example, if you plant chicory seeds on September 1st, they will mature around November 15-25, roughly 3-4 weeks after the first frost. To reduce bitterness of the harvested crop, it must be kept cool but not extremely cold, and moist but not saturated. This also suits the typical fall/winter PNW climate, which is a nearly constant light rain in about 40-60°F.

Aspect of a slope determines whether a slope faces predominantly toward the midday sun or away from it. The steepness of a slope in turn governs the relationship according to the sine of the sum angle above the horizon and that of a slope facing it, or of the difference in angles where the slope is facing away. Winter chicories should therefore be planted on the southern side of a slope to receive the most sun and greatest warmth during cold months. In summer, chicories might fare better on the northern slope, where shade would help keep radicchio cool. Cool temperatures prevent stress on the plants, which can reduce their bitterness and increase their biomass. Cooler temps will produce sweeter tasting chicory; cooler temps will produce sweeter tasting chicory. You want to make sure you soil is loose, well drained, and moist, but not wet- make sure to water the base of the plant and not is foliage. Chicory can withstand light frosts, but heavy freezes can cause damage to the taproot, if there is a worry about deep freezes, it is best to plant the winter chicory in a raised bed for warmth and extra drainage.

Downy mildew, anthracnose, fusarium wilt, Septoria blight, white mold, bacterial soft rot, sclerotinia cottony rot, tip burn, damping-off and bottom rot are all diseases, fungal infections, pathogens and parasites which can affect chicories. Micro-pests of chicories include slugs, snails, aphids, darkling beetles, flea beetles, leaf miners, loopers, and thrips are all insect predators of chicories. To deter slugs and snails, practice good garden sanitation by removing garden trash, weeds and plant debris to promote good air circulation and reduce moist habitat for slugs and snails; handpick slugs at night to decrease population; spread wood ashes or eggshells around plants; attract them by leaving out organic matter such as lettuce or grapefruit skins, destroy any found feeding on lure; sink shallow dishes filled with beer into the soil to attract and drown them. Macro-pests of cultivated radicchios are deer and rabbits who eat the leaves, and voles who eat the plant from the taproot upward. Fencing can help deter larger pests, as can things like shiny ribbons tied around the perimeter of the garden, rubber snakes, and predator (coyote or fox) urine. Insect pests may be deterred in several ways. Introducing insect predators, controlling weeds, removing plant debris, promoting good air circulation, rotating crops, creating well-drained soils and raised beds interplanting with other greens, and watering in the morning can all help reduce insect issues with radicchio. Deterrents for fungal infections, pathogens and parasites which can affect chicories include planting seed under optimal conditions for quick emergence and vigorous growth, using sterile soil or potting mix to start seeds, disinfecting any tools and equipment that might be used, managing irrigation to reduce periods of high humidity, planting rotations using non-susceptible crops such as grass or grains, and encouraging maximum air movement between rows.

•#1d: Case Study Tasting Research: Radicchio

Content by Macka B.

From the perspective of a consumer, what is your opinion, solution, and/or concern about having access to local vegetables throughout the winter months?

Access to seasonally appropriate produce is important to me as a consumer because I feel it is one way that I can contribute to healthier local food systems. Winter vegetable subscription boxes might be a fun way to get food to people; if the farmer/co-op supplied recipes along with the boxes it would ensure that people know how to use the produce, and I think they would be more likely to buy it in the future. I am also in love with events like the Winter Vegetable Sagra, as they represent a rare opportunity for breeders, farmers, and chefs to meet and evaluate input from consumers, creating relationships with seasonal foods that consumers might otherwise not know about or know how to utilize.

From the perspective from a grower/farmer, what is your opinion, solution, and/or concern about having access to local vegetables throughout the winter months?

As a farmer, winter vegetables represent a continuous value stream through a time of the year that is generally not productive. Covered soil is happy soil, and planting winter crops can help to prevent pest, disease and erosion issues and also improve the quality of your soil for the following spring. Growing cover crops in the winter makes your soil healthier and increases fertility. More specifically in the PNW, growing diverse winter vegetables can “break the green bridge” when it comes to brassica.

Do you think it is always feasible to only shop for vegetables that are in season for your local region?

This is a hard question because feasibility is relative; as with everything else, money buys privilege. If you have enough time and money, anything is feasible. At its heart, this question is about food justice: who has access to what and at what cost? For me, it is not feasible to exclusively buy locally sourced fruits and vegetables, but I do make an effort. I specifically rely on what might be considered luxury products, specifically citrus and avocados. I do try to shop and forage locally and freeze that produce to use for the rest of the year, offsetting my need to buy veggies out of season.

Having watched, listened, and read about radicchio over the last two quarters, what recipes, meals, and/or products are you excited to try, or have tried? Were they a success?

This weekend I’m planning on preparing radicchio (and possibly endive) in a few ways. Grace, Ali and I are planning a small dinner party, and we are hoping to utilize some portion of every one of our taste studies from winter quarter. I am thinking of two radicchio dishes: a salad and a risotto.

I want to make a Caesar salad built from frisee, with crispy polenta croutons. The anchovies, olive oil and lemon in a Caesar dressing should complement any bitterness in the frisee perfectly, and the frisee is sturdy enough to stand-up to the heavy dressing. The warm, crispy polenta croutons will complement the buttery frisee perfectly.

I’m also excited to try making a radicchio risotto. Instead of wine, I will be deglazing the Arborio rice with an incredibly smoky Lapsang souchong tea. I will also be utilizing seaweed in the vegetable stock I’ll be using in the dish. I think I will use a head of the Forced Treviso Tardivo for the radicchio addition.

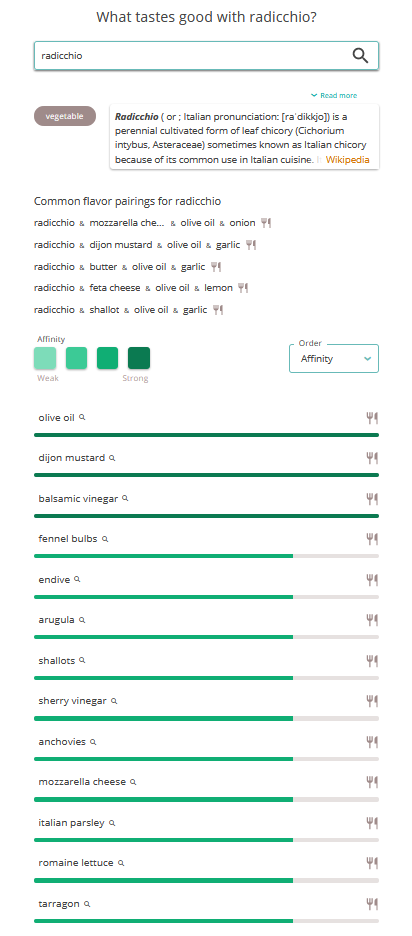

Now that we have been exposed to many different foods and drinks, and have a deeper understanding of our own perception of flavors, how would you ‘build your lexicon’ in relation to the flavor complex of radicchio? What categories and/or words might you use? Use the CBN’s Winter Squash Flavor Wheel (squash wheel) for inspiration.

I was surprised at the fatty, nutty, almost buttery taste of the frisee; I still have a fairly limited experience with radicchio, so my first objective will be continuing to taste as much as I can. I will also continue cooking with it, as it seems universally agreed that cooking radicchio completely changes its flavor profile. I will also continue to pair radicchio with other foods; over and over I have heard radicchio described as an ensemble vegetable. Perfectly explained in this quote from the article “The Age of Radicchio Is Upon Us” by Leah Koenig, quoting Raquel Pelzel, author of the recently published cookbook Umami Bomb, “Serving radicchio is about partnering it with the right sidekicks. Like the juicy tanginess of citrus…a sharp and salty hit from shaved parm, or the funk of blue cheese. Radicchio is more about the composition than the singular.”

•#1e: Stuckey’s Taste Book Experiments

•#1f: Sustainable Entrepreneurship

•#1g: Climate and Resilience Event Series/Seminar

•#1h: Foodoir: Your Story of Tasting Place

For Samin Nosrat, it’s all about the details, ensuring that every bite is perfect—even when making a simple salad.

Created by Food & Wine, December 12, 2018.

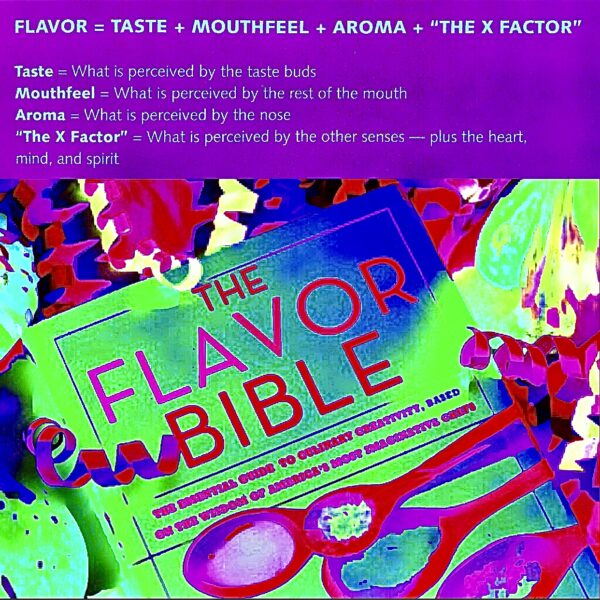

The Flavor Equation, Kulinarian, Pairings and Affinities

The Flavor Equation

Flavor = Taste + Mouthfeel + Aroma + The X Factor

Taste: What is perceived by the taste buds.

Mouthfeel: What is perceived by the rest of the mouth.

Aroma: What is perceived by the nose.

The X Factor: What is perceived by the other senses — plus the heart, mind and spirit.

Leave a Reply