•#4a: Film Series: Program Questions in Scenes

“The Animated Clam”

Animations by Mat Sesti

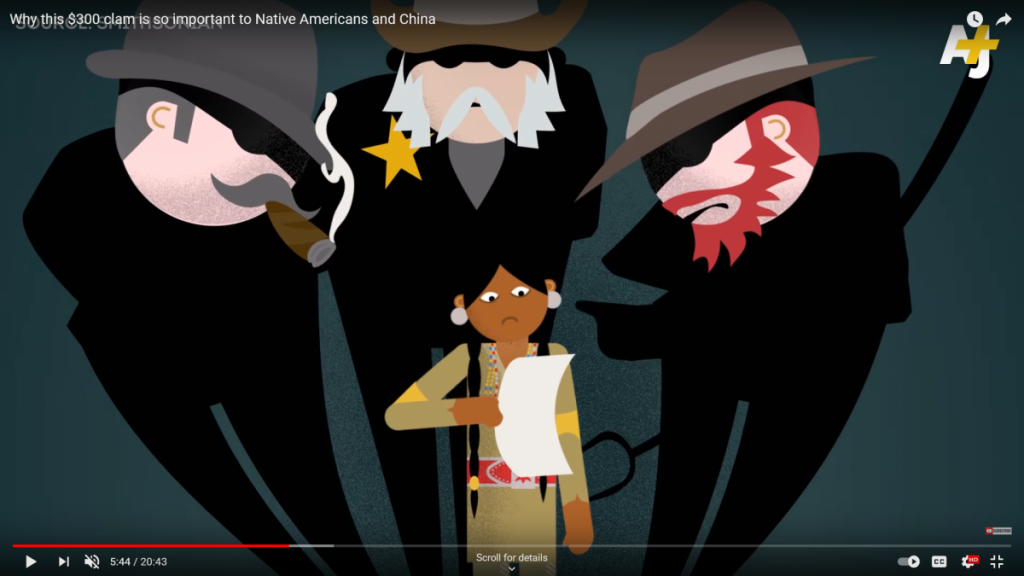

I titled my scene from the Al Jazeera short film Why this $300 clam is so important to Native Americans and China, “The Animated Clam” (5:30 – 8:12) to explore the program question “What representations of terroir/meroir are most compelling and why? What blueprint (model) best enables you to articulate what and how you’re learning about your sense of taste of place in relation to rapid sensory evaluation, history, nature, and culture?” I will call my audience’s attention to the use of animation as the medium for the scene and why it is both useful and effective, discuss the use of symbols to convey information and emotion, talk about the choice to personify some “characters” within the animation while leaving others true to life, and applaud the film makers choice to incorporate sections of live footage between animated portions of the scene, creating visual metaphors to underline the complex concepts.

I’ll share how this scene generally compelled my learning surrounding food sovereignty and the history of indigenous land and water rights, and specifically how the use of animation in the scene was successful, in order for my audience to understand how multiple techniques, communication styles, and narrative strategies are successfully incorporated into the production, providing a richer and more thorough treatment of the subject than live action footage alone.

The choice to use animation as the medium for this scene was extremely effective for several reasons; foremostly, the use of animation allows the film makers to explore a complex idea like indigenous food sovereignty and the historical ramifications of treaty rights in a simplified, easy to understand way. Furthermore, animation is used in my scene to portray an undocumentable event because cameras didn’t exist during some of the time periods being covered; through animation we can “see” what happened as opposed to being told what happened using an interview or reenactment. The scene begins with a flood of white colonizers to indigenous land in the Pacific Northwest, and from the first moment the animators utilize both basic and complex symbols to communicate.

For example, 5:44 in the scene presents three white men wearing black looming over an indigenous man; the white characters continue to grow and loom heavier as time passes, obviously putting-out a threatening vibe. However, if one continues looking closer at the primary symbol of the looming men, other deeper elements begin to become apparent. One man is holding a club/pitchfork behind his back, reinforcing the threat of violence which these men pose while simultaneously adding the idea of agriculture to the conversation. Another of the men wears a sheriff’s badge, representing the law. The final man smokes a cigar, symbolic of colonialism, wealth, and the relationship of the US government to indigenous people, some of whom find tobacco to be highly spiritual. The use of facial expression in the animation is a simple visual that has great impact.

The first visual component of the scene is the frowning face of a white settler; throughout the scene, watching the often-exaggerated facial expressions of the characters connects the physical world and the world of abstract symbols. The scene goes on to show the Treaty of Medicine Creek, the year 1854, and then a reservation literally springing-up from the ground to surround the indigenous characters; this part of the scene illustrates another benefit of animation: the ability to exaggerate. Here, the film maker doesn’t think we need to hear how reservations were established, but instead provides us with a simple visual narrative in which we can see that they appeared fast and are small, constrictive, and unhappy. The personification of the US government as a giant hand and arm wearing an Uncle Sam costume is an interesting choice and influences the viewer to see the government as a giant who might crush the first peoples if it chose. The dismissive gesture that the hand gives as it drops the money further mirrors the dismissiveness of the government.

We next see an indigenous fisherman utilizing traditional salmon fishing tools like the fishing spear and nets. This is shown in contrast to white fishermen with poles; again, we see the white character smoking tobacco, bastardizing an indigenous spiritual practice. We also see here the only reference to the environmental degradation caused-by deforestation and pollution, which I wish had been more thoroughly explored in connection to the other forms of colonial oppression visited on first peoples concerning fishing rights and food sovereignty. The scene shifts again to indigenous fishers on their reservation land being admonished by another “long arm of the law”, this time Washington State in a gray suit, who jails them. Notice that the jail demolishes the reservation, symbolic of the damage to the culture and way of life of indigenous peoples.

In a brilliant action by the film makers, they chose to embed historical live footage of the “Fish Wars” within the animated section of the film. The live footage is evocative, stirring the emotions, and an animated version of the police beatings and arrests would not have had such an impact. In fact, by sandwiching the inflammatory footage between animations, the live footage is possibly even more impactful than if it had been shown in a string of other live scenes because the rawness, grittiness and brutality of them are contrasted so heavily by the clean, bright animation.

The next portion of my scene again personifies the US federal government and Washington State; The United States is literally embodied by the capitol building, stepping across the map to confront Washington. Again, easily recognizable symbols such as the hammer and gavel and scales are introduced to inform the narration about pertinent court cases, such as the 1974 Boldt Decision and the 1994 Rafeedie Decision, which produced the 50/50 rulings which are animated directly after. It is interesting to note that personification within the animation only extends to government bodies and institutions and bypasses people and creatures entirely. The geoduck, possibly the most animatable creature on the planet, is shown true to life. In a way this makes the federal government (shown as a walking capitol building with Groucho Marx eyebrows) funnier looking than the geoduck, which is absurdist and thought provoking. I also applaud the animators for being respectful of indigenous dress, never creating a caricature of indigenous people and culture; within a medium like animation, which can and somewhat is expected to present exaggerated characters and scenarios, the choice to treat indigenous culture with sense of realism is refreshing.

“Blue Sky, Blue Water, Blue Women”

Produced by Cable News Network (CNN), In Marketplace Africa (Atlanta, GA: Cable News Network (CNN), 2019), 11 minutes

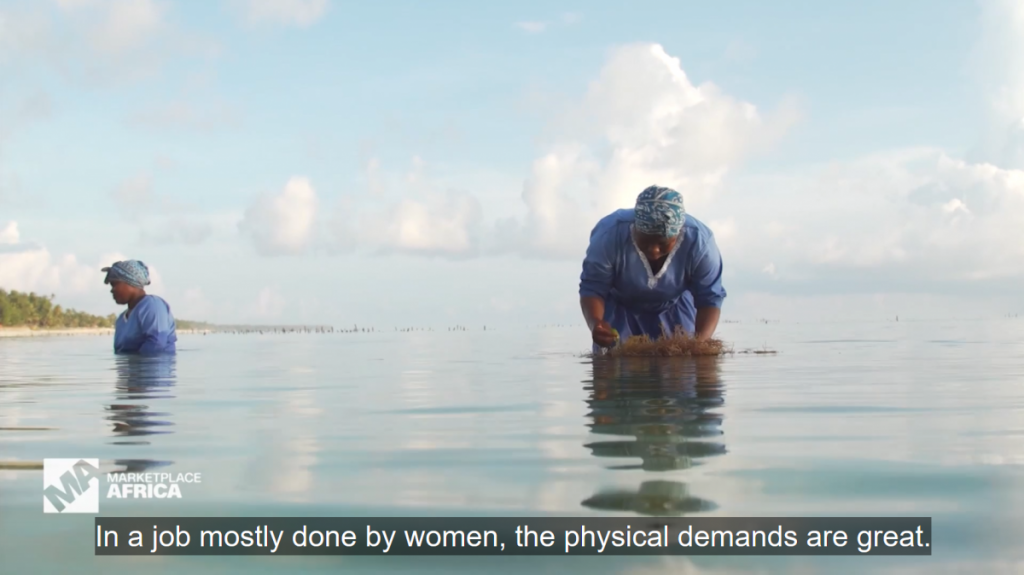

I titled my scene from the CNN Marketplace Africa report Zanzibar’s Female Seaweed Farmers, “Blue Sky, Blue Water, Blue Women” (1:25 – 5:29) to explore the program questions “What blueprint (model) best enables you to articulate what and how you’re learning about your sense of taste of place in relation to rapid sensory evaluation, history, nature, and culture?” and “Where and how do people raise the foods we are highlighting?” I will call my audience’s attention to the Seaweed Centre’s mixed purpose of tourism and mariculture, the uniform blue dresses of the women juxtaposed against the colorful, patterned kangas of the other farmers and the CEO’s contrasting outfit, and the phrase “It’s such a beautiful place, with such beautiful ingredients.”

My scene begins with a brief shot of women seaweed farmers in Zanzibar wearing extremely colorful, patterned kangas, or traditional dresses. The scene shifts to the Seaweed Centre and Mariam Mgoile explaining the hard work involved with seaweed farming. It is immediately noticeable that the women of the Seaweed Centre are uniformed in solid blue dresses of a western style, in contrast to the other seaweed farmers bright and patterned garments. The next shot shows us the women of the Seaweed Centre wading in the ocean. The blue dresses blend-in with the sky and sea, visually blending the women into the surroundings. The narrator punctuates the scene of the blue-clad women working, explaining that work for women in Paje is scarce, and that the jobs are generally limited to tourism and seaweed farming; Mariam appears again, telling the audience that she was a boutique sales lady before coming to work for the Centre. At this point in my scene, it was becoming apparent that the Seaweed Centre functioned as something between agriculture and tourism; the uniforms of the women are meant to appeal to tourists and the Western gaze. The women become idealized and pastoralized, their blue dresses blending into the background.

The CEO, Klaartje Schade, is interviewed next, explaining the Centre’s employment of women as a means to provide a better income and an easier living by working 95% of the time in company’s production rooms rather than the sea farms. As the CEO walks across the production floor in a bright coral, European style dress, the juxtaposition of clothing is once again front and center. The European owner is set apart by her style of dress, standing in contrast to her uniformed employees. I was once again struck by the women’s uniforms and the seeming modern colonialism at play, and reminded of the purpose of uniforms: signaling who is the consumer and who is there to serve/entertain/help/etc.

Shots of women harvesting seaweed are followed by shots of workers on the production floor making soap; the narrator goes on to explain that 50 kg of dry seaweed is worth about $20, while the women of the Centre create soap and beauty products which sell for $5-$10 per item, and are exported to Europe and the US, as well as being purveyed by boutiques and luxury eco-hotels in Africa. The women are being paid a higher wage for their work, but they are providing the double labor of farmer and tourist attraction. The final words spoken by Schade, “It’s such a beautiful place, with such beautiful ingredients”, echoed at the end of my scene, assigning value to the land and the ingredients but not the women. I was left grappling with a sense of neocolonialism that was presented through the story of clothing, whose ending is directly focused on what can be taken as opposed to given back in the community.

The crop that put women on top in Zanzibar

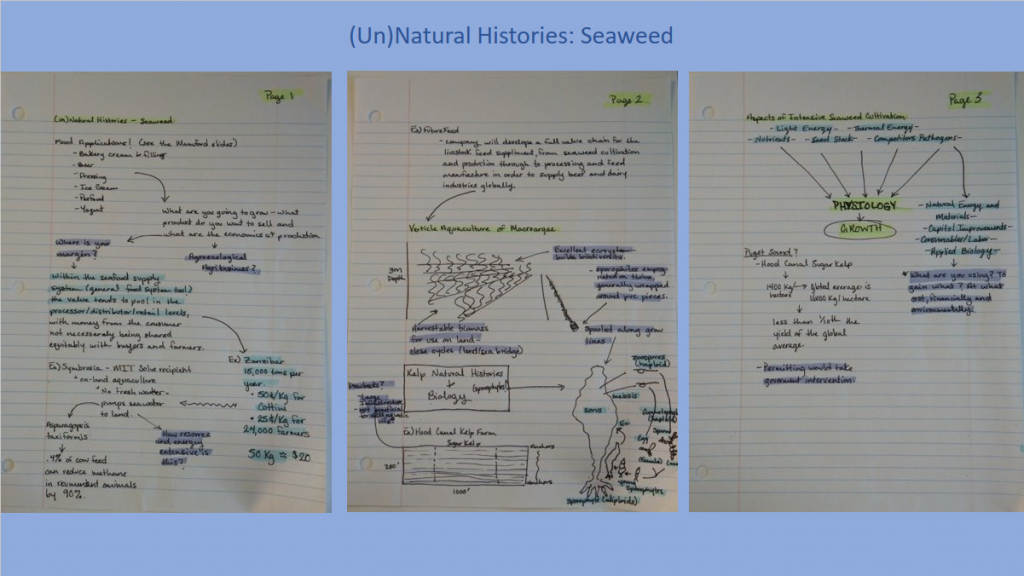

•#4b: (un)Natural Histories

•#4c: Regenerative Agriculture

What impact did the Bolt decision and associated court cases have for Native American rights and access to marine resources in the state of Washington?

1974 Boldt Decision and the 1994 Rafeedie Decision guarantee that half of all harvestable fish and shellfish in the state of Washington belongs to Native American communities, providing a guarantee that indigenous peoples will be able to fish their traditional waters and beaches.

Describe the life cycle of the geoduck (from one adult generation to the next adult generation).

Geoducks are broadcast spawners, which means that reproduction isn’t based on being able recognize members of the opposite sex. They are also dribble spawners, meaning that eggs and sperm are released several times over the spawning season, typically late winter to early summer, with the greatest activity in May and June. Mature males release millions of free-swimming sperm; the triggered by rising water temps and other environmental cues. The presence of sperm in the water stimulates mature females to begin spawning, releasing up to 5 million eggs at a time. Females can release up to 10 batches of eggs a season.

In its first phase of metamorphosis, the geoduck is a trochophore: a larva barely visible to the naked eye. It begins to acquire accessory organs (velum) that is a parachute appendage used for swimming. After the larva’s shell forms it enters the pro-dissoconch stage. In the dissoconch stage, the geoduck loses its velum and sprouts a set of spines on the outer edge of the shell. It drops from the upper water column to settle on the seafloor and by the end of the second year it will reach full adult size and a depth of around 3 feet.

How can farming geoducks in the Salish Sea improve water quality by removing excess nitrogen from the water?

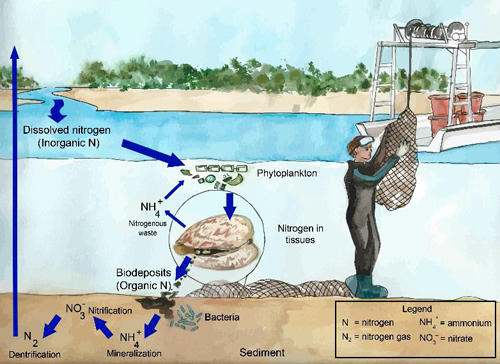

Image by University of Florida IFAS research and extension faculty.

Filter feeders like geoducks (and other bivalves) remove nitrogen and phosphorus from the water column, and these nutrients may ultimately be removed from the ecosystem via harvest of cultured bivalves. Clams do not absorb nitrogen directly from their environment, rather they feed on naturally-occurring phytoplankton, which use dissolved inorganic nitrogen, available in the water, to grow. Thus, clams incorporate nitrogen from their food into their tissues and shells. When clams are harvested, the accumulated nitrogen is removed from the water. Clams also play an important role in the cycling of nutrients, including nitrogen. For example, clams release nitrogenous waste (urine) that can be used by phytoplankton as a source of nitrogen. In addition, some of the nitrogen filtered from the water by clams is deposited to the sediment as feces and pseudofeces (rejected food particles). These biodeposits are decomposed by bacteria, which transform the nitrogen to a variety of other forms, including ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3-), and nitrogen gas (N2). Because of this nutrient removal ability, bivalve aquaculture can improve water quality and mitigate eutrophication pressure in coastal systems like the Salish Sea if the ecological carrying capacity is not exceeded.

As a climate change mitigation strategy, do you think it is reasonable to claim that geoduck aquaculture releases less carbon dioxide per kg of animal protein than the same quantity of protein derived from land-raised livestock. Why or why not (justify your answer)?

Yes, it is reasonable to claim that geoduck release less carbon dioxide compared to land raised livestock. Geoduck do not release the same methane gas as cows do. They also filter the water consuming phytoplankton, trapping that carbon that would eventually be release back into the water ways when the phytoplankton decompose.

Why is plastic used in current geoduck farming methods, and can you imagine an alternate strategy to avoid plastic use in the Salish Sea?

Photography by KBCS 91.3 Community Radio/Flickr.

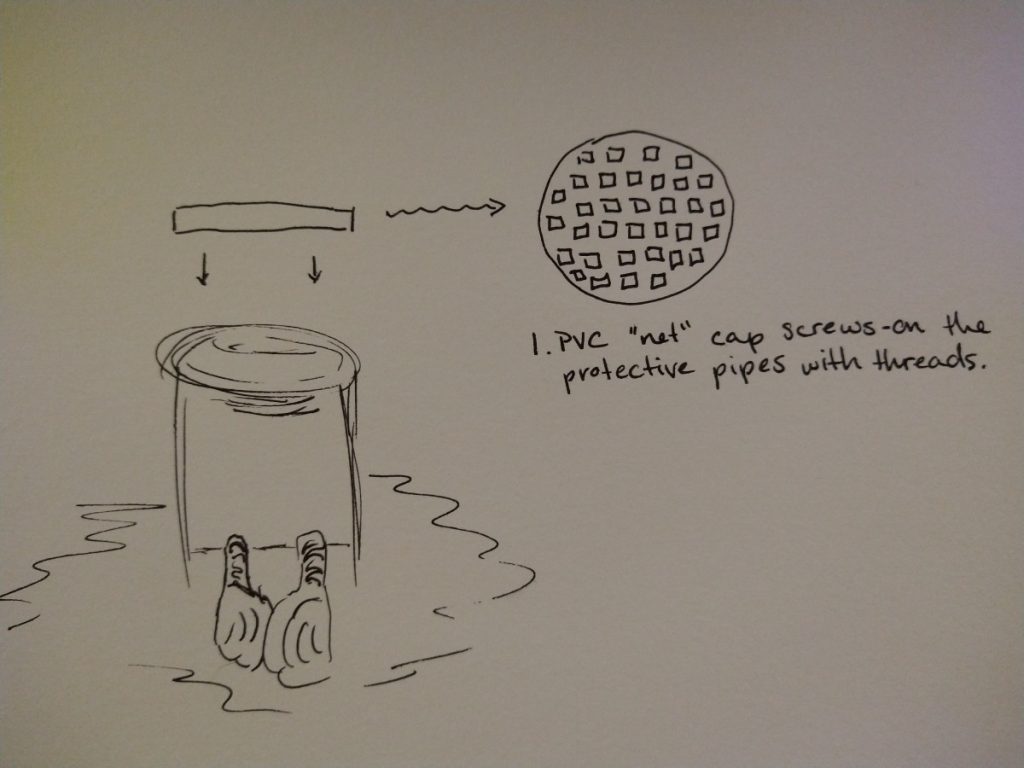

Four to five juvenile geoducks are planted inside PVC tubes that are “wiggled” into the sandy substrate along the intertidal zone during low tide. The plastic tubes are covered with a mesh net to protect the clams from predators. The tubes also serve to retain seawater at low tide, which prevents dehydration of the clams. After one to two growing seasons when the juvenile geoducks have burrowed themselves deep enough into the substrate to be out of reach of predators, the PVC tubes are removed. When geoducks are planted in the subtidal bed, the area is covered with netting to protect the clams from predators (PVC tubes are not stable in subtidal beds due to strong currents).

To reduce the amount of plastic lost in the Salish Sea, particularly the small net covers for the PVC pipes used to protect young geoducks in the first two years, I thought that utilizing a permanent PVC “net”-cap could be effective. I also thought that using a larger net secured over the entire geoduck bed might be more stable than using separate netting for each pipe.

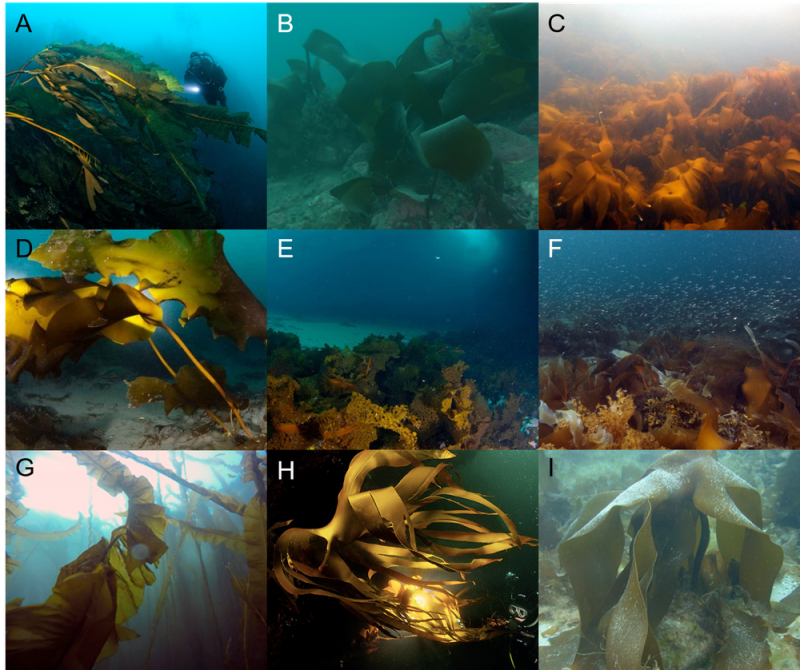

Describe the generalized life cycle of a kelp species (from one diploid generation to the next diploid generation).

Kelp reproduces by means of spores. Kelp has two life cycles: diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte. The haploid starts when the mature kelp releases spores; these spores then germinate to become male or female gametophytes. Sexual reproduction starts the beginning of the diploid stage where they will develop into a mature kelp.

How can farming seaweed in the Salish Sea improve water quality by removing excess nitrogen from the water?

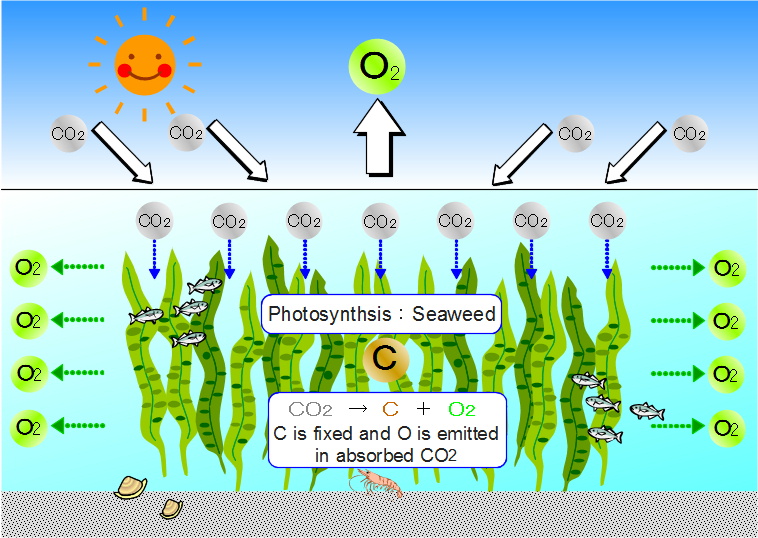

Some cultivated seaweeds have very high productivity and could absorb large quantities of N, P, CO2, produce large amount of O2 and have excellent effect on decreasing eutrophication in the Salish Sea. That seaweed can then be harvested for human consumption, fertilizer, and animal feeds.

Describe how carbon dioxide emissions are causing ocean acidification.

Photography from Sea Doc Society.

When CO2 is absorbed into the water, H2O attaches to that CO2 to form carbonic acid H2CO3 which then breaks down H+ and bicarbonate HCO3-,causing the decrease of pH. This is represented with this chemical reaction:

CO2 + H2O -> (H+) + (HCO3-).

Given acidifying ocean waters, describe how growing seaweed near shellfish can improve the ability of shellfish to create their calcium carbonate shells.

The metabolic activity of macroalgae, photosynthesis and respiration, result in strong diurnal pH fluctuations. This suggests that calcifying organisms that inhabit these ecosystems are adapted to this fluctuating pH environment. Seaweed dominated environments may have the potential to act as an ocean acidification buffering system in the form of a photosynthetic footprint, by reducing excess of CO2 and increasing the seawater pH. This can support calcification and other threatened physiological processes of calcifying organisms under a reduced pH environment. The degree of ocean acidification buffering capacity caused by the metabolic activity of macroalgae might depend on community structure and hydrodynamic conditions, creating site-specific responses.

Image by Japan Water Guard.

To scale up seaweed aquaculture as a blue carbon strategy for climate mitigation, describe some of the research, regulatory and/or market issues that need to be addressed to facilitate scaling up ocean production.

Promoting seaweed aquaculture as a component of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies requires that all four dimensions of the social-ecological system that supports seaweed aquaculture be addressed: (1) biological productivity to enhance carbon capture, (2) environment constraints to the expansion of seaweed aquaculture, (3) policy tools that enable seaweed aquaculture, and (4) manage societal preferences and markets demands for seaweed products. Maintaining a market price that encourages seaweed farmers to engage and implement design improvements to maximize climate services delivered by the farm requires that markets diversify to increase the demand for seaweed products. Subsidizing farmers, either directly or indirectly through tax abatement, for farms credited as blue carbon seaweed farms may further increase engagement with this strategy. While the contribution of seaweed aquaculture to climate change mitigation and adaptation will remain globally modest, it may be substantial in developing coastal nations and will provide add-on value to the societal benefits derived from seaweed aquaculture.

To scale up the use of seaweed used in cattle feed as a strategy to reduce bovine methane emissions, describe some of the research, regulatory and/or market issues for:

- Seaweed production

To supply the volumes of seaweed that would be needed by the beef and dairy industries, strategies that enable the efficient and sustainable production of seaweeds of consistent quality need to be developed through aquaculture. The first challenge will be to identify the ideal cultivars, or blends thereof, that possess both the qualities desired by end-users (i.e., potent methane reduction, safety, palatability, etc.) as well as the ability to be cultivated at scale. In addition, there is a need to understand how location, season, breeding, processing and other factors impact quality and consistency of the end-product. In many countries, a consistent, streamlined, inter-state policy framework for seaweed production is needed to provide regulatory certainty and encourage investment and industry expansion. Policy researchers, ecologists, and regulatory agencies, in collaboration with seaweed farmers, must also consider social license to operate, particularly in nearshore environments where coastal landowners may perceive seaweed farming as an activity that would negatively impact property values.

- Animal Feed Production

Large-scale animal feeding operations and feed manufacturers require consistent volume, quality and safety of raw materials. In addition, new feed ingredients must not displace critical protein, carbohydrates, minerals, and other nutrients in the diet. Therefore, it is likely that seaweeds would need to be used as feed additives, which are generally defined as <1% of the dry matter intake (DMI) of an animal’s diet. Even as a feed additive, supplying the livestock industry with sufficient seaweed may be a challenge. The estimated 3–3.4 MMT of dried seaweed required per year would represent over half of all seaweed currently produced globally. Supplying the global herd −1.4 billion cattle—would not be feasible, however it is presumed that widespread use of methane mitigants in smallholder or subsistence production systems is unlikely to occur due to cost and other limitations.

In addition to quality control issues related to the consistency and activity of seaweed raw materials, producers will need to determine best methods for drying or otherwise reducing the large amounts of water contained in fresh seaweed, as the wet weight would present a major challenge to transporting seaweed from production sites to processing facilities. Feed manufacturers will need to consider any special encapsulation or protective methods that might be needed for delivery and to increase shelf life, in addition to the by-products that will be produced and how to reuse waste materials.

One of the greatest challenges feed manufacturers face in developing seaweed-based feed ingredients is compliance with industry regulations. Animal feed ingredients are highly regulated in many countries, with approval processes like foods for human consumption. In the U.S., feeds must typically meet animal and human safety standards, with thorough documentation of supporting data and methods used to obtain it, as well as detailed descriptions of the manufacturing process, toxicology of any potentially harmful substances in the ingredient, proof of consistent manufacturing, and a proposed legal definition for the ingredient.

In addition, feed manufacturers must find ways to produce seaweed-based feed ingredients that are compatible with the feed manufacturing and handling systems used by the industry today. For example, seaweed products for the animal feed industry need to be in dry form for inclusion into mixed feed ingredients, have concentrated active compounds to allow for low inclusion rates, have sustained activity over time to meet reasonable shelf life requirements of the ingredient alone and in mixed feeds, be able to withstand transportation and processing such as pelleting or extrusion, be palatable to animals, have a known and consistent nutrient profile, and be cost effective for the feed manufacturers and their customers.

Finally, since quality and effectiveness of a seaweed product may be modified during the feed production, storage and mixing processes, the efficacy, safety, and stability of the final formulation must be evaluated prior to commercial application.

- Livestock Production

Both short- and long-term animal trials are needed to comprehensively evaluate the use of seaweed in cattle production. Short-term studies should determine which seaweed species have the greatest potential to reduce methane. These studies should also evaluate impacts on animal productivity (e.g., beef and milk production), feed intake, animal health, product quality, active compound residue in edible food products and potential changes in manure composition. Further, as both polymeric and simple carbohydrates in seaweed are very different from land-grown feed, studies on the digestibility and energy value of these carbohydrates for cattle production is required. Longer-term animal trials are also needed to further evaluate the effects of selected seaweeds on methane emissions, productivity, health, product quality, digestibility of nutrients, active compound residues in manure, and manure GHG emissions. Feeding approaches for seaweed products will need to accommodate differing production systems, as effects may be influenced by breed, diet, climate, geography, and other variables. Development of a commercial seaweed feed product must include mitigation of any safety or environmental hazards, including the presence of halogenated compounds.

Since our knowledge of the microbiome and its contribution to animal health is still in its infancy, metagenomic studies are imperative to understanding how certain seaweeds impact the rumen microbiome and whether these effects could be manipulated to benefit animal health and productivity, as well as the environment.

For livestock producers, it is also important to evaluate the economic benefits of any future seaweed product. Even if regulations mandate the use of seaweed or other products to reduce methane emissions, farmers’ financial burden could increase if animal performance is not improved simultaneously (e.g., improved productivity, efficiency, health, or product quality). The value of the improvement must therefore be enough to cover the cost of the product or additional incentive programs will need to be established to achieve widespread adoption.

•#4d: Case Study Tasting Research: Seaweed

Meroir of the PNW: Geoduck & Seaweed Tasting

Emily Wilder, seafood influencer and geoduck ambassador, graciously gave her time and energy to our program, presenting an overview of geoduck and seaweed and presenting a tasting of the latter.

Needed:

- 4 mugs or canning jars

- Boiling water (during the 10:45am break)

- A thermos with additional hot water

- Seaweed samples

- Your favorite tea (black, green, or herbal)

- Dinner plans

Geoduck “Tasting”

What does a geoduck taste like?

Geoduck is very sweet and slightly briny.

What is Q?

Q is a springy, chewy texture. Most typically pronounced simply as the English letter “Q”, or the cutesier form “QQ”, some also say tan ya, which brilliantly translates as “rebound teeth.” Mouthfeel of tapioca pearls, gummy worms, or mochi. Geoduck is said to have a high level of Q.

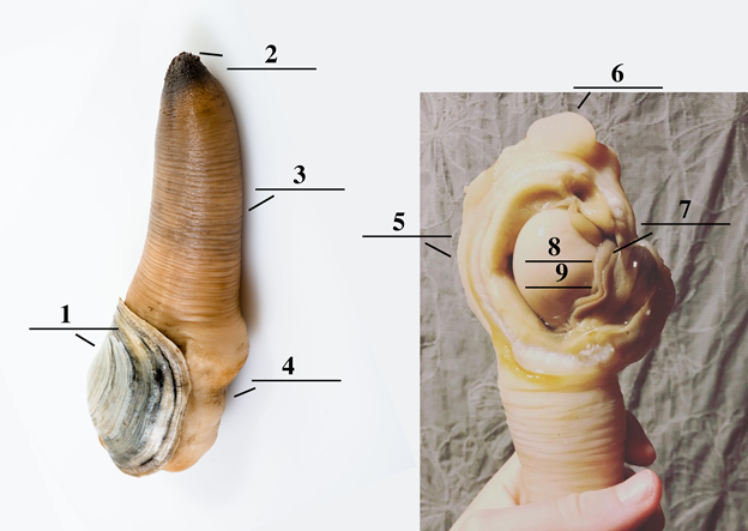

Label the parts of the geoduck:

- Shell

- Tip

- Siphon

- Belly

- Mantle

- Foot

- Gills

- Labial Palps

- Visceral Ball

Seaweed Tasting

Directions:

Please heat up your water, and set up the following 4 cups:

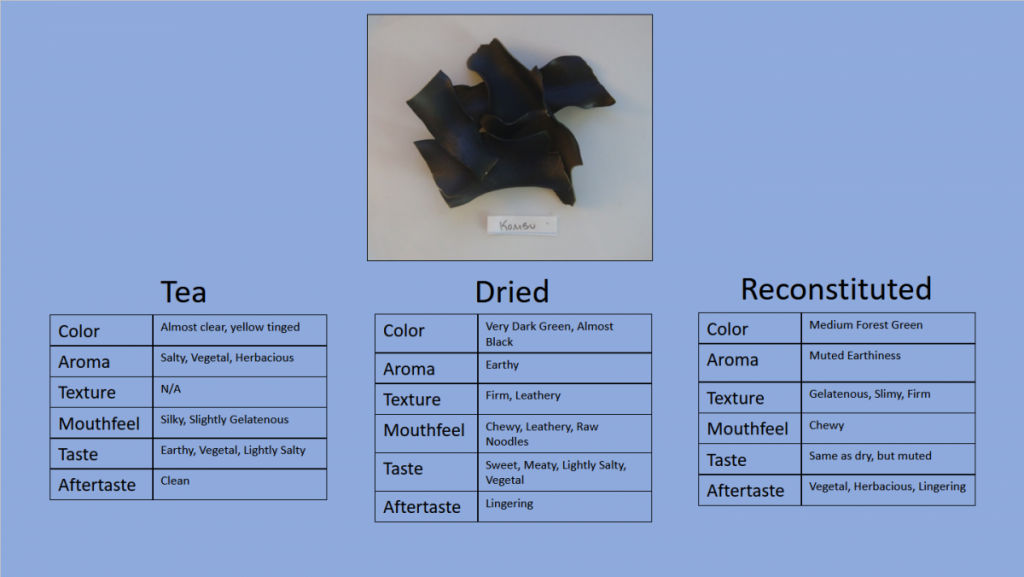

- One piece of kombu (roughly 3”x1”)

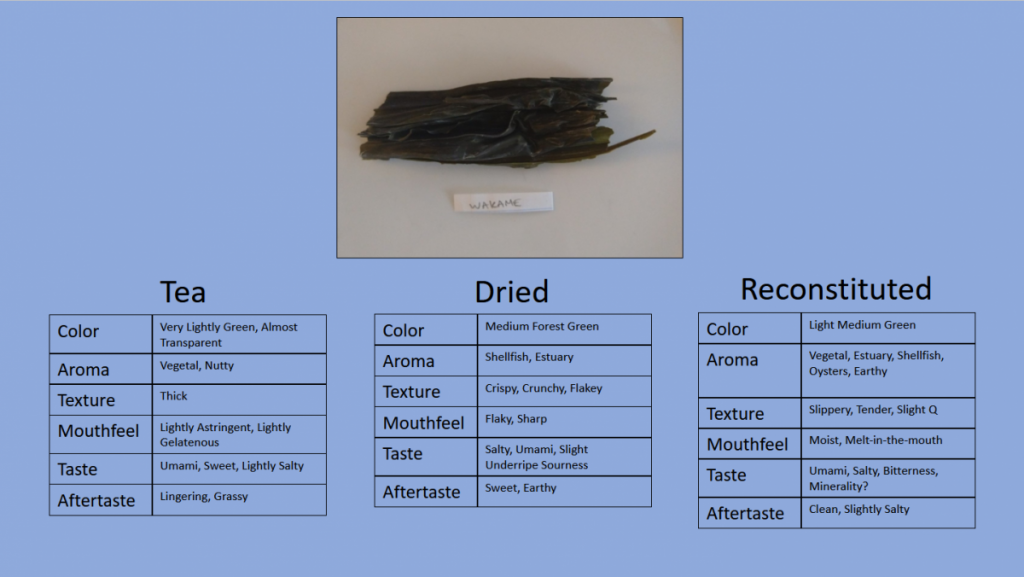

- A couple pieces of wakame (roughly 3”x1”)

- The equivalent amount of sea palm (about 8 pieces)

- Your favorite tea + a piece of wakame

You’ll pour boiling water in each of the seaweed cups and let them steep, but wait to add water to your favorite tea until we start tasting the seaweed, so the tea is not over-steeped (it will be the last thing we taste).

What are the three seaweeds we are tasting today?

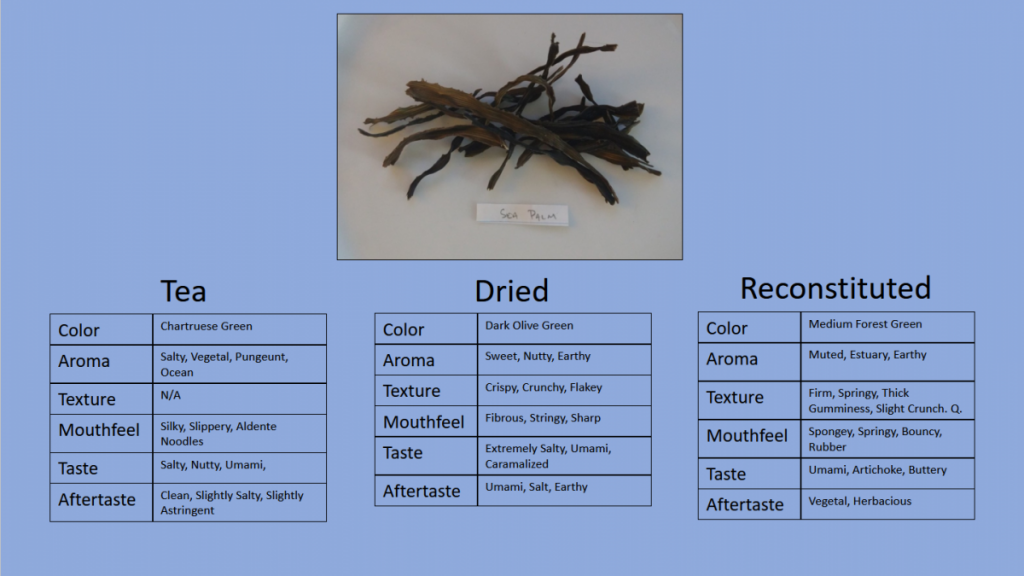

We tasted Sea Palm, Wakame, and Kombu.

Wakame is a species of edible seaweed, a type of marine algae, and a sea vegetable. It is most often served in soups and salads.

Kombu is sold dried or pickled in vinegar or as a dried shred. Kombu is used extensively in Japanese cuisine as one of the three main ingredients to make dashi, a soup stock.

The sea palm is found along the western coast of North America. It is an edible annual, though harvesting is discouraged due to the species’ sensitivity to over-harvesting.

What type of seaweed are they?

All three types of seaweed we tasted are macroalgae, also called kelp.

What are the health benefits of seaweed?

Seaweeds are high in Vitamins C and E, Omega 3’s, Iodine, Iron, Calcium, Riboflavin, and Fiber. In addition they are prebiotic and have enzymes which aid in the digestion of legumes.

What is the biggest threat to the ocean right now?

Ocean Acidification is possibly the most pressing threat to the ocean right now. When CO2 is absorbed into the water, H2O attaches to that CO2 to form carbonic acid H2CO3 which then breaks down H+ and bicarbonate HCO3-, causing the decrease of pH. Even slight changes in pH can be devastating for delicate aquatic ecosystems.

Photography by Sarah Dyer.

Reflection

What were some of your favorite geoduck and or seaweed dishes presented today?

I really loved the sea palm as a dried snack, so that is my favorite overall; I feel like I could eat it everyday! But, I would be excited and willing to try all the recipes and preparation mentioned.

Have you ever eaten geoduck? If yes, please tell the story. How was it prepared? What did you think?

I love to eat fish, shellfish, and basically anything from the ocean, so trying geoduck for the first time was a real treat. In the first week after moving to Olympia, my partner and I cooked seafood paella for his parents as a show of appreciation for letting us stay and become settled before finding an apartment. I LOVED it and it suited the dish perfectly, combined with fresh squid and mussels. I also bathed a few pieces in hot, melted butter to cook them to temperature, which gave the clam a buttered mushroom texture and an indescribably rich taste. One of my favorite seafoods.

What other foods have you eaten that have Q?

Q is one of my favorite textures, and I love boba tea with tapioca, mochi, gummy candies, shellfish, seaweed, tripe, tendon and cooked mushrooms.

Would you order a geoduck shipped to your house? If yes, how much would you be willing to pay for it? If no, why?

I would probably have a geoduck shipped to my home if I didn’t live so close to Taylor’s Shellfish Farm; when given the option of time and space, I would rather pick-out my own geoduck. If I lived further from Western Washington I would consider having a geoduck shipped for $50.

What would you make with geoduck if the sky was the limit?

If geoduck wasn’t as expensive, I would love to make a beautiful, creamy clam chowder. I love New England Clam Chowder (its one of my favorite foods), and I think the geoduck meat would elevate the taste, giving it a richer, sweeter base with large pieces of shellfish. I would also love to try the indigenous way of fire-smoking the clam.

Have you ever eaten seaweed before? If yes, what was your most memorable time? If no, what stopped you from eating it?

I have eaten seaweed before, mostly of the dry, snack variety and as a wrap for sushi. I’ve also had a seaweed salad served with sushi, but after a bad experience involving sun sickness paired with whole baby octopus and seaweed, I’ve been turned-off by seaweed salads.

What tea did you experiment with adding seaweed to today? Did they complement each other, or detract? What kind of tea do you think would pair well?

I used a green tea with a piece of Kombu, and I think that the two suited each other really well. I appreciated the vegetal, umami, almost brothy taste and texture of the mix.

How did you prepare the leftover seaweed? Share recipe details if you want, and Emily might feature it on her website!

I am still holding-on to my seaweed, but I plan to do some hiking over the spring break and will take the seaweed along as a light snack or flavorful broth base that weighs almost nothing. I am excited for the idea of seaweed as a seasoning agent on other foods, so I would like to try crushing the wakame seaweed and mixing it with pepper, tarragon, and lemon peel for a fish or shellfish seasoning. I’m also interested in making pesto with seaweed and figuring out how it pairs with radicchio.

Anytime Meal of Champions: ? Waka Waka May May ? @blueevolution #wakame #seaweed , organic #toasterroasted #sweetpotaters , @3sistersmarket #grassfedbeef , @sanjuanislandseasalt, @sofrabakery #aleppochili flakes, and #butterbutterbutter . #DidYouKnow : Sweet potatoes are super high in beta-carotene (which converts to the essential #vitaminA ), #butt this amazing nutrient is #fatsoluble , so you must #eatitwithfat ! So, add the butter. A little more.

I am so inspired by Emily Wilder’s Instagram! Beautiful food, thoughtfully prepared and presented. With a smile and a wink.

What did you learn from Annie’s research structure and focus? Please share your notes.

I truly enjoyed Annie’s blog, Meroir Sustainability: Seaweeds Through Taste, History, and Climate Change; I particularly liked her section on identification of seaweed, and I was surprised to learn that all kelp is edible. I was so inspired by her ability to pivot after finding that she couldn’t forage, creating a space to succeed when she could have easily become overwhelmed. I appreciate her thesis, tying together taste, natural histories and climate change, and hope to visit her site regularly for updates.

And speaking of foraging seaweed, I couldn’t help thinking of my favorite tiktoker Alexis Nikole, aka BlackForager. I wondered if she had ever posted a seaweed foraging video and was elated to find this excellent video all about Dead Man’s Fingers.

Video by Miss Mina

•#4e: Stuckey’s Taste Book Experiments

The experiments done in this lab are all taken from Barb Stuckey’s book, Taste and adapted from the work of Caleb Poppe.

The Experiment

- “Taste What You’re Missing: Experiencing Mutual Suppression” – Page 192 & 193

Salt is a necessity to nearly all savory meals and many of the sweet desserts that restaurants have to offer. While it is not completely understood what is taking place on a microscopic level as we eat salted foods, it is undeniable that adding salt to most meals only enhances the flavors that the food has to offer. Salt is a necessity to our bodily functions as well; perhaps salted foods taste better to us because we know, on a cellular level, that salt is preservative and necessary.

Sweetness, as well, is an all-too-common aspect of the food we eat. Carbohydrates (starches & sugars) are an integral part of most diets, and our body breaks these down primarily to make glucose, which is a simple sugar that we burn for energy. All of this is to say that, over time, the human body has become well attuned to the presence of sweet, and yet the flavor profile of sweetness is quite complex.

Bitterness is a basic taste that has an altogether different importance than that of salt and sweet. Bitterness is complex and is usually associated with toxic compounds, and because of this, it is believed that humans evolved our palates to have a direct aversion to bitter foods as well as a love/hate attraction to bitter’s intensity.

Having experimented with the 5 basic tastes, the program has a good understanding of the differences of between Salty, Bitter and Sweet compounds. In the following labs, we examined the three of these basic tastes as a whole, rather than individually, in order to gain fresh perspective as to how we enjoy them in our day-to-day lives.

Materials for the lab:

- Bitter Nail Tea

- 4 clean cups

- Spoon

- Boiled water

- Table Salt

- Sugar or Honey

- Palate Cleanser (saltine crackers, lemon water, etc.)

General Questions:

Of the 5 basic tastes, which do you believe your body craves the most?

I have an incredible sweet tooth, and tend to crave it most of all the 5 basic tastes, though salty and umami follow very close behind.

Do you have a specific (or favorite) way to enjoy that basic taste?

My favorite sweet treats are cinnamon rolls or snickerdoodle cookies. Sweet and cinnamon is probably my favorite combination.

Taste What You’re Missing: Experiencing Mutual Suppression – page 192 & 193

Stuckey calls this experiment the “Mutual Suppression of Flavor” because we took a massively bitter tea and attempted to suppress that bitterness with both salt and sugar. When we had all the supplies set up, we placed the bitter nail tea into a single mug and added 16 ounces of boiling water; this tea was poured into our other cups, and we steeped the tea for 15 minutes.

Photography by Sarah Dyer.

With our remaining three cups, we added sugar and salt. In the first cup we added 2 tablespoons of sugar (Sugar Only Cup), in the second cup we added ¼ of a teaspoon of salt (Salt Only Cup), and in the third cup we added 2 tablespoons of sugar AND ¼ of a teaspoon of salt to the cup (Salt & Sugar Cup). Once the tea was done steeping, we added 4 ounces of the tea to each cup and stirred them, leaving 4 ounces of the tea with no sugar or salt added to it. Once the tea was poured and the salt and sugar were dissolved, we tasted each of them, paying attention to how the bitterness changed forms.

Photography by Sarah Dyer.

Experiment Questions:

What was your initial reaction to the bitter nail tea with nothing added to it?

I generally dislike bitter foods, but I LOVED this tea. It was the most complex bitterness that I have ever tasted, and instead of being assaulting, it was bracing and refreshing.

How did the bitterness change between the different cups containing sugar and/or salt?

The sugar intensified the bitterness, and the salt seemed to dull the bitterness. Most surprisingly, the mixture of the two (salt & sugar) tasted even bitterer than the original bitter nail tea.

There seems to be two groups of coffee/tea drinkers: people who enjoy the drink in its unaltered form, and others who like to modify it with fats and sugars. Give different example of a way we humans alter classically bitter foods or drink to make them more palatable.

We add sugar and dairy to cacao to produce chocolate, and we caramelize bitter vegetables like radicchio, or roast them with fat, to draw out their natural sweetness and mellow the bitter flavor profile.

What are your thoughts on regionally/culturally acquired flavor preferences? Do you believe that flavor preference is a learned behavior, instinctual, or a mixture of both? When you taste a flavor, when does its objectivity end and your subjectivity begin?

I think flavor preference is both learned behavior and instinct. If we are fed the same foods from childhood onward, I think we might develop a preference for those foods. However, because taste is a completely subjective ability that is the sum of all parts of a persons food memory, we might lose a taste for a food we love, gain an appreciation for something new, or dislike foods for any number of reasons other than taste: sight, smell, texture, sounds, and memories.

•#4f: Sustainable Entrepreneurship

I’ve begun calling week two of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Futures for Food and Agriculture, “Aldous Huxley on Business”. I mean this with all due respect, alluding to the fact that the lecture this week cracked the doors of my perception a wee bit in relation to business, economy and capital enterprise.

As shared by Tamsin Foucrier.

Sustainable Entrepreneurship

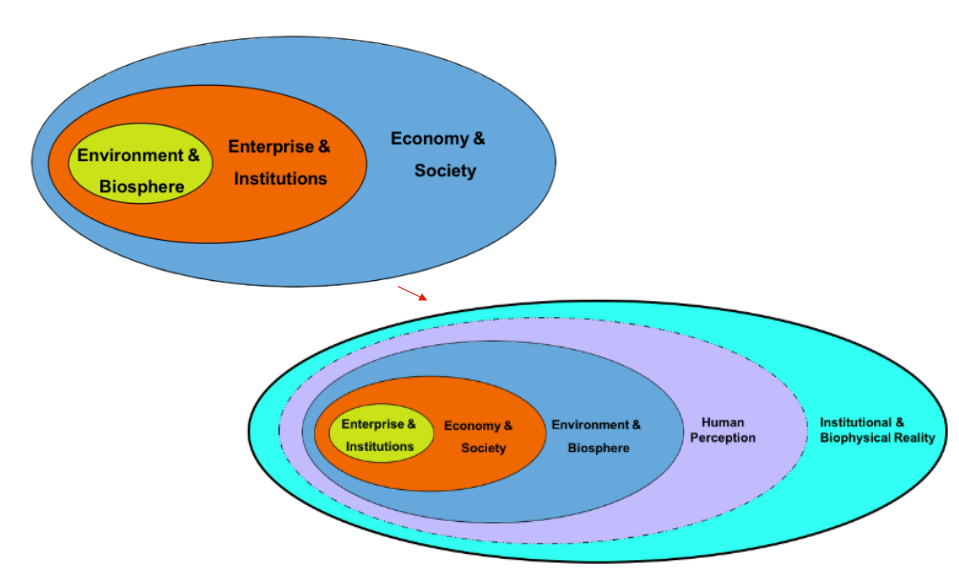

We began with the ‘classic’ model of sustainability, the 3 P’s: Planet. People. Profit. In exploring this concept, we utilized a phenomenal infographic-style short film, which pointed-out the critical flaw at play in the 3 P’s, namely that each circle within the diagram is the same size, which implies equal importance or value. This, of course does not reflect the biophysical realities of our world. Instead, we find ourselves working toward a nested image in which business and society are embedded in nature, as everything exists in nature at some point.

With our newfound understanding of the failures of the 3 P’s approach to sustainability, we began to explore the current reality of our economy. This reality asserts that enterprise and society has control of the environment, a reality in which a tree only has value based on the goods and services it can produce, in which no inherent value exists in the environment and its only value exists in its capacity as a commodity to be bought, sold and traded by the marketplace.

Designed and presented by Sustainability Illustrated via YouTube.

As Tamsin put it, these narratives and assumptions are “baked into our bones”, and so we are challenged to “move beyond ” and reimagine what business can be. This shift involves an understanding that we exist in an environment bigger than ourselves and have developed our economies, societies, enterprises and institutions. We are bound by the limits of our environment and biosphere.

So, bound by the limits of our human perception and our historical assumptions surrounding business, enterprise, and capitalism, we as budding sustainable entrepreneurs might feel quite limited in our ability to innovate and think-through old paradigms. We are left with two ideas to guide and shape our understanding of these models. One: We are governed by biophysical realities which CANNOT be changed by our perception. And two, sustainability in enterprise and business involves reshaping our understanding of how these nested circles relate and interact, how they have done so in the past, and how they might in the future.

Image by Tamsin Foucrier.

In truth, I am cynical of capitalism or any other system that commoditizes the basic needs of people and the environment. If food is a right, if water is a right, if housing is a right: how can we justify talking about markets, premium products or value editions? How can we prop ourselves up on a system that is so broken and that has failed so many? My experiences and assumptions weigh heavily, but I will leave the door of perception open just a crack to let in the hope that a functional, sustainable and equitable system can exist and that I will live to see substantive change in my lifetime.

•#4g: Climate and Resilience Event Series/Seminar

Video created by The Evergreen State College Productions.

As part of the Climate Justice series of events at The Evergreen State College, I had the opportunity to attend the Sámi National Day webinar: Sámi Perspectives on Green Colonialism: Response to Climate Change. The event centered the perspectives and voices of Sámi people in Sápmi who represent activists, scholars, educators, reindeer herders, fishers, and artists. We were all asked to think about the following central question of the event: How can we best support Sámi efforts to ensure that solutions to climate change do not undermine Sámis’ UN-recognized rights to land, language, and culture–all of which are interconnected?

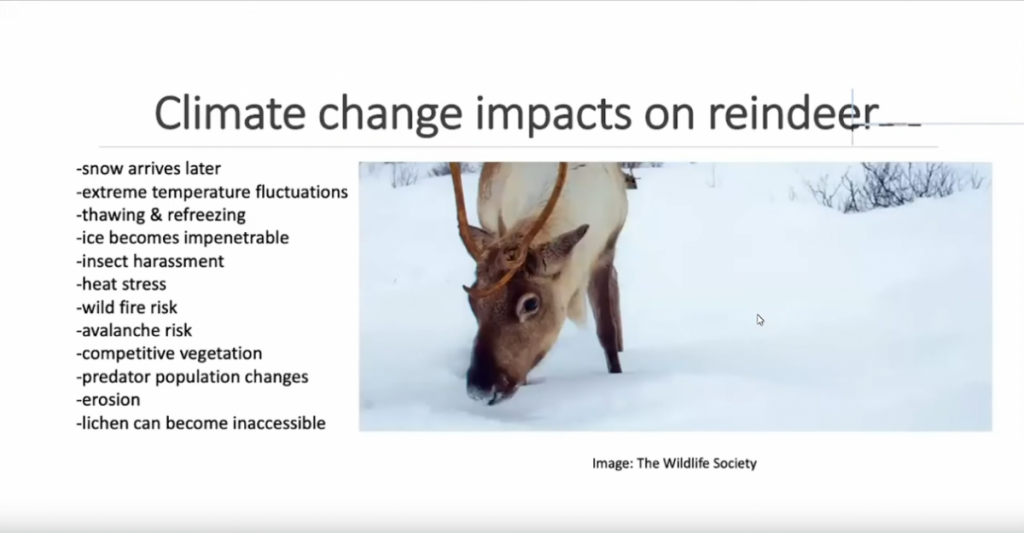

I was especially moved by the conditions facing reindeer herders, briefly described between minute 2:32 – 3:05 by Marja Eloheimo. She says, “While not every Sámi works directly with reindeer the importance of reindeer to Sámi culture can’t be overstated reindeer have always provided food and materials community and relationships and a sense of being in time and place, but nation states have disrupted all of this including migration between summer grazing areas and the plants they contain and winter grazing areas with the all-important lichen.”

She goes on to say, between 5:14 – 5:53, “The impacts of climate change are on top of all of this with temperatures increasing in the arctic two to three times faster than other parts of the world, and these impacts on reindeer are tremendous. You can see many examples here and I’ll just emphasize that in many conditions the snow becomes like ice and like sheet metal and the lichen becomes inaccessible. We’ll hear more about this and other direct impacts of climate change from our guests.”

Video created by The Evergreen State College Productions.

Photo: Brage B. Hansen.

In a later talk with Stefan Mikaelsson, (21:53 – 22:49) who was involved with traditional reindeer husbandry from 1977 to 2005, facilitator Elle Márjá Jensen asks him, “What are reindeer herders in Sweden seeing as far as climate change that’s happening, what do they see?” He answers, “We can see the dangerous diseases and also this kind of parasites are coming north. And we also see that the lichen area is declining or suffering because of the dangerous rain, rainfalls. And the rains are not always so good because they have different kinds of chemicals in them so the area for grazing has obviously diminished. The lichen area has diminished 71% since 1953 and up to today. Not everything is because of climate change, but this is one of the factors that affects the lichen coverage.” Over the last few decades, the warming climate has brought more rain and less snow in some winters. These can cause ice to form on the ground. The ice coats the reindeer’s preferred food and causes them to starve— a potential catastrophe.

The conjunction of this climate event with our study of seaweed, particularly as a possible addition to the ruminant diet, led me to dive deeper into the issues at play surrounding so called rain-on-snow (ROS) events and their impact on Sámi reindeer herds. I began to wonder if abundant seaweed grows in the Arctic, if reindeer could eat seaweed, and if so, could it become a ready source of supplementary feed for Sámi herds during ROS events? The answer was surprising, intriguing, and complicated.

Image via Karen Filbee-Dexter.

It turns out, kelp is prolific along rocky coasts throughout the Arctic. Kelps have adapted to the severe conditions; the cool water species have special strategies to survive freezing temperatures and long periods of darkness, and even grow under sea ice. In regions with cold, nutrient-rich water, they can attain some of the highest rates of primary production of any natural ecosystem on Earth.

So, will the reindeer eat it? In the face of climate change, reindeer are resorting to eating kelp, according to new research. The creatures in question are Svalbard reindeer, a sub-species of wild reindeer. As their name suggests, they’re native to Svalbard, an archipelago about halfway between Norway and the North Pole. Historically, seaweed was not part of the diets of these reindeer, but researchers have determined that, when ground ice is thicker, reindeer make for the coast and the kelp. Conversely, they don’t eat seaweed when they don’t have to.

Photography by Brage B. Hansen

And, the reindeer don’t totally switch diets. “It seems they can’t sustain themselves on seaweed,” biologist Brage Hansen explained in a press release. “They do move back and forth between the shore and the few ice-free vegetation patches every day, so it is obvious that they have to combine it with normal food, whatever they can find.” Despite their apparent ability to digest kelp, the seaweed is taking a toll on the reindeer: diarrhea, which is thought to be caused by the salt content.

If there’s a silver lining, it may be the reindeer’s adaptability in the face of adversity. Not all species are as fortunate. “Although we sometimes observe that populations crash during extremely icy winters, the reindeer are surprisingly adaptive,” Hansen adds. “They have different solutions for new problems like rapid climate change, they have a variety of strategies, and most are able to survive surprisingly hard conditions.” That said, the researchers are yet to examine the effect of the change in diet on the reindeer’s nutritional intake.

So could the Sámi use seaweed as a supplement for their herds during ROS events? Maybe, but there are multiple variables at play which must be resolved. Research would need to be conducted on the impact of kelp on the reindeer’s traditional diet. The salt content of unprocessed seaweed is too high for reindeer to eat reliably; in order to function as more than emergency fodder, kelp would have to be desalinated, which is an expensive, energy intensive, and requires specific equipment. Fore-mostly, while archaeologists have found evidence of the Nordic use of seaweed in the past, particularly in Iceland and Greenland, it does not appear to be a functional part of the Sámi food and fishing culture.

However, at least in wild herds, the reindeer are choosing seaweed on their own. And with some research and technology, using kelp to help feed Sámi reindeer could cut back on expensive grain feed and allow the Sámi people an excellent means of climate adaptation for ROS events that is within their means to harvest.

•#4h: Foodoir: Your Story of Tasting Place

“If food is poetry, is not poetry also food?”

Joyce carol oates

“Take away this pudding. It has no theme.”

Winston churchill

“When you know where your food comes from

you can give something back to those lands & waters,

that rural culture, that migrant harvester,

curer, smoker, poacher, roaster or vinyer.

You can give something back to that soil,

something fecund & fleeting like compost

or something lasting & legal like protection.

We, as humans, have not been given

roots as obvious as those of plants.

The surest way we have to lodge ourselves

within this blessed earth is by knowing

where our food comes from.”

Gary Paul Nabhan, January 2007, ” A Terroir-ist’s Manifesto for Eating in Place”

How to Eat Your Words: Food Poetry

The process of preparing a meal could be compared to the process of writing a poem. Maya Angelou said, “Cooking is like writing poetry… You want the best ingredients. When you’re writing a poem, you hope to have a good vocabulary, and to choose the nouns and pronouns and verbs carefully. The way you put them together will determine how they affect another person. And it’s really because you’ve been careful in the choice of your ingredients and respectful of how they work together. That’s true of all the efforts in life.”

Gathering ingredients is like collecting words, and we might savor a meal as we do a particularly pleasing phrase. The descriptive qualities inherent in poetry make it a compatible partner to food and cooking; and, as food utilizes all of our senses, it serves as the perfect palate for image driven poems.

Quarter Life Crisis

At fifteen I don’t see

thirty on the horizon, a faint glow

veiled by a haze of years. Blind,

I wander open-mouthed in awe

and catch dust in my teeth

more often than not.

By twenty-two I begin to harden

the nacre walls around my troubles. Rising higher,

the dead white sun is caught

in the water; I grasp for the reflection

and come up empty.

Around twenty-five I drown

in questions that rush over me

like rip tides. I surge forward

and then back. Treading water

until the weighted whys pull me below

the surface, so far away

even the light can’t reach me.

Twenty-nine:

I slip my knife between

shell and flesh, and wonder,

lifting a briny shuck to my lips,

if thirty years isn’t a little too long to wait

for pearls, each lustrous orb a hardship

lodged in the throat of an oyster.

Sarah dyer, 2014, Originally published in Wire harp

Poetry Foundation Collection: Poetry and Food

[POETRY] National Poetry Month Food Prompts!

Produced by Button Poetry.

•#4i: Bibliography

@geoduckgal. “Anytime Meal of Champions: ? Waka Waka May May ?”. Pikuki, 2021, https://www.picuki.com/media/2515650325374284485.

“2017-18_shellfish.Pdf.” Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Ajbani, Serena, et al. Why This $300 Clam Is so Important to Native Americans and China. Performance by Yara Elmjouie, YouTube.com, Al Jazeera, 22 Nov. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=IrsPxHbbOqo.

Ash, Lucy. “The Crop That Put Women on Top in Zanzibar.” BBC News, BBC, 2 July 2018, www.bbc.com/news/stories-44688104.

Baurick, Tristan. “Farmed Geoduck’s Sustainability Rating Takes a Hit.” Kitsap Sun, Kitsap Sun, 5 Feb. 2017, www.kitsapsun.com/story/news/local/2017/02/05/farmed-geoducks-sustainability-rating-takes-hit/97410252/.

Bookey, Justin., Atkins, Chet, DJ Krush, Coolbellup Media, and Bottomfeeders. 3 Feet under: Digging Deep for the Geoduck. Seattle, WA: EMFATIK, 2003. Web.

Boyle, Katherine. “The Poetry of Cooking: Maya Angelou, ‘Great Food, All Day Long’.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 4 Mar. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/express/wp/2011/01/05/maya-angelou-great-food-all-day/.

California Academy of Sciences. Demystifying Ocean Acidification and Biodiversity Impacts (Video). Khan Academy, Khan Academy, www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/biodiversity-and-conservation/threats-to-biodiversity/v/ocean-acidification-and-biodiversity-impacts.

Chisholm, Chris. “Eating From The Seashore: Seaweeds & Shellfish of the Salish Sea.” Wolf Camp & School of Natural Science at Blue Skye Farm, 24 Aug. 2020, www.wolfcollege.com/edible-seaweeds-and-shellfish-of-the-salish-sea/.

Cox, Justin. “Ocean Acidification & the Health of the Salish Sea.” SeaDoc Society, SeaDoc Society, 15 Aug. 2020, www.seadocsociety.org/blog/ocean-acidification-amp-the-future-health-of-the-salish-sea.

Cubillo, Alhambra Martínez, et al. “Ecosystem Services of Geoduck Farming in South Puget Sound …” Https://Www.fojo.org/, Aquaculture International, 2018, www.fojo.org/papers/geoduck/Cubillo%20et%20al%20geoduck%20AQINT.pdf.

Danner, Stephanie, and Casson Trenor. Monterey Bay Aquarium, 2008, pp. 1–38, Seafood Watch® Wild Geoduck Report.

Dua the Dietician. “[POETRY] National Poetry Month Food Prompts!” Dua the Dietitian, 5 Apr. 2018, duardn.com/blog/poetry/poetry-national-poetry-month-food-prompts/.

Duarte, Carlos M, et al. “Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation?” The Pathway to Solutions: New Frontiers in Climate Change Adaptation & Mitigation, Frontiers in Marine Science, 12 Apr. 2017, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2017.00100/full?RefID=EM2287_MktPartner_VOCES15.

Fernández, Pamela A., et al. “Co-Culture in Marine Farms: Macroalgae Can Act as Chemical Refuge for Shell-Forming Molluscs under an Ocean Acidification Scenario.” Taylor & Francis, Phycologia, 13 Nov. 2018, www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00318884.2019.1628576.

Filbee-Dexter, Karen. “Underwater Arctic Forests Are Expanding with Rapid Warming.” Phys.org, Phys.org, 14 May 2019, phys.org/news/2019-05-underwater-arctic-forests-rapid.html.

Fisher, Mary Francis Kennedy. The Gastronomical Me. Daunt Books, 2017.

“Fishing and Shellfishing Licenses.” Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, wdfw.wa.gov/licenses/fishing.

Foucrier, Tamsin. “Introduction to Sustainability.” Zoom. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Futures for Food and Agriculture, 17 Jan. 2021, Olympia, The Evergreen State College.

“Geoduck Aquaculture.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 Jan. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoduck_aquaculture.

Gordon, David G. Field Guide to the Geoduck. Sasquatch Books, 1996.

“Green” Clams: Estimating the value of environmental benefits ecosystem services generated by the hard clam aquaculture industry in Florida. University of Florida: Institute of Food and Agricultural Science, Gainesville, Florida. FDACS P-02023 Rev. 11/20.

“Green Colonialism in the Arctic: Introduction.” YouTube, YouTube, 9 Feb. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=lmRjfsG5SMY.

“Green Colonialism in the Arctic: Stefan Mikaelsson.” YouTube, YouTube, 9 Feb. 2021, www.youtube.com/watch?v=EGGA6eTrzJI.

Hansen, Brage Bremset, et al. “Reindeer Turning Maritime: Ice‐Locked Tundra Triggers Changes in Dietary Niche Utilization.” The Ecological Society of America, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 23 Apr. 2019, esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ecs2.2672.

Home, www.oceanacidification.org.uk/.

“How Is Bitter Different From Sweet? It’s All In Your Brain.” Vox Creative, Eater, 2 Feb. 2016, www.eater.com/sponsored/10893890/how-is-bitter-different-from-sweet.

“Introducing HSU’s New Seaweed Farm, a First for California [Video].” Humboldt State Now, 11 Sept. 2020, now.humboldt.edu/news/the-first-seaweed-farm-in-california/.

Jessee, Annie. Merrior Sustainably : Seaweeds through Taste, History and Climate Change, 2021, merrior-seaweed-jessee.squarespace.com/.

Kart, Jeff. “Hawaiian Seaweed Makes Cows 90% Less Gassy – And That’s Good For Climate Change.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 23 Nov. 2020, www.forbes.com/sites/jeffkart/2020/11/21/hawaiian-seaweed-makes-cows-90-less-gassyand-thats-good-for-climate-change/?sh=11721b005c4b.

KBCS 91.3 Community Radio. “Taylor Shellfish Geoduck Farming in the Puget Sound: Geoduck Aquaculture Is Controversial, and Industry Growth with Current Techniques Isn’t Sustainable, University of Washington Scientists Have Reported.” Everything You Need to Know About Geoducks, Eater, 17 July 2016, www.eater.com/2016/7/17/11691958/what-is-geoduck.

Nabhan, Gary. “A Terroir-Ist’s Manifesto for Eating in Place.” Gary Nabhan, 22 Jan. 2007, www.garynabhan.com/news/2007/01/a-terroir-ists-manifesto-for-eating-in-place/.

“New Company Puts Foot on the Gas to Reduce Cows’ Methane.” CSIRO, 21 Aug. 2020, www.csiro.au/en/News/News-releases/2020/New-company-puts-foot-on-the-gas-to-reduce-cows-methane.

Nikole, Alexis. “Spooky Season Means Spooky Seaweed Gathering! ??.” TikTok, 7 Oct. 2020, www.tiktok.com/@alexisnikole/video/6881089830516788486?lang=en.

Oh, Mina, director. COASTAL FORAGING ? Butter Clams, Mussels, Seaweed, Crabs! CATCH & COOK Kelp Soup & Chowder. YouTube, YouTube, 2 July 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=JMa6x1NVKG0.

“Personal Life.” International Churchill Society, 6 May 2009, winstonchurchill.org/resources/reference/frequently-asked-questions/personal-life-faq/.

Pence, Truen, director. How Chef Jacob Harth Harvests and Cooks Wild Seaweed — Deep Dive. Performance by Jacob Harth, YouTube.com, Eater, 24 Oct. 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=urG-vM6jcYg.

“Poetry and Food.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation, www.poetryfoundation.org/collections/145091/poetry-and-food.

Rendlemen, Charity. “Joyce Carol Oates.” lit216 [Licensed for Non-Commercial Use Only] / Joyce Carol Oates, 2016, lit216.pbworks.com/w/page/43621220/Joyce%20Carol%20Oates.

Sammon, Alexander. “Meet the Women Growing the California Seaweed Economy.” Civil Eats, 23 Mar. 2018, civileats.com/2018/03/23/meet-the-women-behind-californias-first-open-water-seaweed-farm/.

“Seaweed Farming Agenda Nov 20, 2019.” Washington Sea Grant, 20 Nov. 2019, wsg.washington.edu/community-outreach/kelp-aquaculture/seaweed-farming-training/seaweed-farming-agenda-nov-20-2019/.

“Seaweed Harvesting: WA – DNR.” WA, Washington State Department of Natural Resources, www.dnr.wa.gov/seaweed.

“Seaweed, Soldiers, and the Fifth Taste: Exploring the Origins of Umami at MOFAD Lab.” Vox Creative, Eater, 30 Nov. 2015, www.eater.com/sponsored/9821538/seaweed-soldiers-and-the-fifth-taste-exploring-the-origins-of-umami.

Smith, Bren. “3D Ocean Farms with Bren Smith of GreenWave.” YouTube, Classy, 11 July 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=jInyeTkpSAE.

Straus, Kristina M, et al. “Effects of Geoduck Aquaculture on the Environment: A …” Marine Aquaculture Extension, Washington Sea Grant, 25 Jan. 2008, www.dnr.wa.gov/Publications/psl_ac_geoduck_lit_review.pdf.

Stuckey, Barb. Taste What You’re Missing: the Passionate Eater’s Guide to Getting More from Every Bite. Free Press, 2012.

The Evergreen State College. “Students of Comparative Eurasian Foodways Feasted on Mussels during Food Lab. Alumna Emily Wilder, ’16, of Taylor Shellfish Farms Stopped by to Give Them an Overview of Shellfish, as Well as Tastings of Oysters and Geoduck. ?#Olywa #Foodie #Pnw #Evergreenstatecollege Pic.twitter.com/PYY6BYqBUz.” Twitter, Twitter, 10 Mar. 2020, twitter.com/evergreenstcol/status/1237390264987054081.

Twohy, Brenna, et al. “Portland Poetry Slam – ‘Choose Your Own Adventure.’” YouTube, Button Poetry, 9 Sept. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=TDnO5hQcCQM.

US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Ocean Today, 8 Dec. 2014, oceantoday.noaa.gov/welcome.html.

Vijn, Sandra, et al. “Key Considerations for the Use of Seaweed to Reduce Enteric Methane Emissions From Cattle.” Frontiers In Veterinary Science, 23 Dec. 2020, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2020.597430/full.

Washington Shellfish Safety Map, Washington State Department of Health, 9 Mar. 2021, fortress.wa.gov/doh/biotoxin/biotoxin.html.

Weinberger, Hannah. “Could Seaweed Be Washington’s next Cash Crop?” Crosscut, Crosscut, 4 Dec. 2019, crosscut.com/2019/12/could-seaweed-be-washingtons-next-cash-crop.

Welch, Craig. “Geoducks, Happy as Clams.” Smithsonian Magazine, Mar. 2009, www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/geoducks-happy-as-clams-52966346/.

Wilder, Emily. “Geoduck_Seaweed Slides.pdf.” 2021.

“Zanzibar’s Female Seaweed Farmers Are Turning Plants into Profits – CNN Video.” CNN, Cable News Network, 17 Apr. 2019, www.cnn.com/videos/world/2019/04/17/marketplace-africa-zanzibar-seaweed-cosmetics-soap-seaweed-centre-vision.cnn.

Leave a Reply