•#1a: Film Series: Program Questions in Scenes

“Open the Bottle and Let it Breathe: The Title Sequence”

Co-Directed and Written by Warwick Ross and David Roach.

I titled my scene from the film Red Obsession, “Open the Bottle and Let it Breathe: The Title Sequence” (0:16 – 2:34) to explore the program question: “How can terroir/meroir best be understood, represented, shared? What disciplines, practices or media are needed and why for knowing and communicating aspects of terroir/meroir?” I’ll call my audience’s attention to these components (things, people, words, music) of my scene: the desolate opening shot, the narrators’ words, the modern aesthetic of the cellar, the music, and the visual special effects.

The opening sequence begins by establishing a wide, uninterrupted horizon shot of a vineyard played at high speed. Light, ethereal music plays. It’s interesting to note that the film Gladiator, starring the narrator Red Obsession, Russell Crowe, used a similar technique throughout. Over this establishing shot, the narrator speaks: “For centuries Bordeaux has commanded an almost mythical status in the world of wine – beguiling kings, emperors and dictators alike. While its survival is dependent on the capricious nature of weather, its prosperity has always been tied to the shifting fortunes of global economies. As powerful nations rise and fall, so does the fate of this place.”

Joss Stone’s slow, sultry version ‘Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ “I Put a Spell on You” plays for the remainder of the credits. The shot shifts to a wine cellar, packed with bottles, which pulls backward along a modern glass walkway, revealing a massive warehouse of wine barrels. The credits reflect in the gleaming glass of the underlit walkway, eventually fading to black before the title of the movie appears in red and white against a black screen. The second half of the opening credits gives the impression, in the best way, of a James Bond film. I’ll share how this scene compelled my learning concerning media and visual representations of terroir for my audience to better understand how the symbolism, music, and visual cues used in this introductory scene set the tone of the movie.

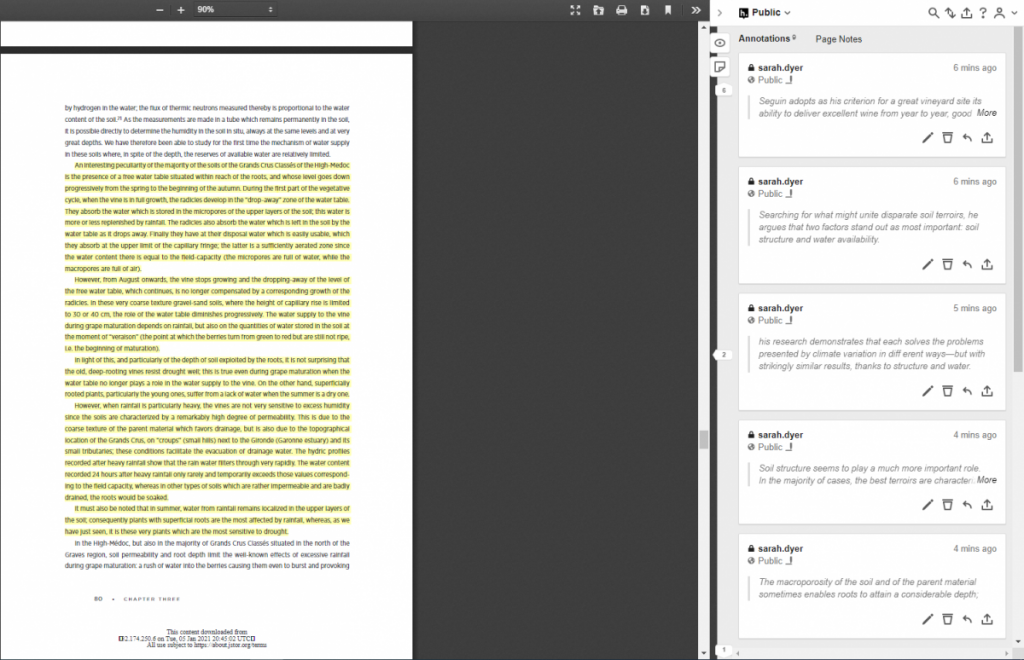

•#1b: (un)Natural Histories

Faculty Librarian Paul McMillan introduced the annotation program Hypothesis.is to the Terroir/Meroir program this quarter, providing a new tool for students to interact with academic resources. We utilized the paper Growing Wine Grapes in Maritime Western Washington, a complete overview and how-to on vineyard management in the PNW. The source is rich, covering everything from site selection and preparation, root stocks and grape varietals, and vineyard establishment and management. I enjoyed working through the document in class; being able to annotate in sync with the lecture allowed me to document my notes quickly and revisit them later, with the added benefit of student and faculty input and discussion. The ability to embed films and links is my favorite feature; being able to associate seemingly disparate or glaringly obvious sources within an annotation allows a tremendous breadth of referential thought for the researcher, expanded ten-fold by the addition of the input of peers.

Image by Sarah Dyer.

Credit: Special Collections, Shields Library, University of California

•#1c: Regenerative Agriculture

Our Week 2 Regenerative Agriculture Workshop focused on wine, including topics ranging the spectrum of terroir: site and climate, soil, vines, grapes, vineyards and wine-making, as well as a Hypothesis.is challenge. I felt that I had to work hard for my answers and research heavily this week, but I also feel more confident and comfortable with this subject matter because I’ve spent so much time with it.

Site and climate

Define site slope: Slope describes the steepness of a hill.

Define site aspect: Aspect describes the direction a hill faces.

Define Macroclimate: Also called regional climate. This is the climate of a region, and the general pattern is described by a central recording station. The macroclimate definition can extend over large or small areas, but typically the scale is tens of kilometers depending on topography and other geographic factors, e.g., distance from lakes or ocean.

Define Mesoclimate: Also called topo or site-climate. The mesoclimate of a particular vineyard will vary from the macroclimate of the region because of differences in elevation, slope, aspect or distance from moderating factors like lakes or oceans. Mesoclimate effects can be very important for the success of the vineyard, especially where climatic conditions are limiting…Vineyards planted at high elevations can lead to cooler conditions for improved table wine quality, compared to the hotter valley floor…Differences in mesoclimate can occur over ten to hundreds of meters, or by up to several kilometers.

Define Microclimate: Microclimate is the climate within and immediately surrounding a plant canopy. Measurements of climate show differences between the within canopy values, and those immediately above it (the so called “ambient” values) …Microclimate differences can occur over a few centimeters…When we consider the climate of a vineyard we are concerned with the macroclimate or mesoclimate. When we consider the climate of or within an individual vine, or part of a vine like a grape cluster, microclimate is appropriate.

Describe what growing degree days measure, how they are measured, and give an example of the GDD for a specific AVA.

Growing Degree Days, or GDD, are a measure of heat accumulation used to predict plant and animal development rates, such as the date that a flower will bloom, an insect will emerge from dormancy, or a crop will reach maturity. GDD are measured through a simple equation:

GDD = Mean Temperature – Base Temperature

Recorded high temperature: 80°F

Recorded low temperature: 60°F

Grape base temperature: 50°F

Mean temperature = 80°F + 60°F/ 2 = 70°F

GDD = 70°F – 50°F = 20

Cumulative GDD is a running total of GDD from April 1 through October 31. For example, the Puget Sound (Mt. Vernon) AVA has 1675 cumulative growing degree days.

Soil

Define soil texture: Texture is defined by the proportions of sand, silt, and clay in the soil.

Define soil structure: Soil structure refers to the grouping of soil particles (sand, silt, clay, organic matter, and fertilizers) into porous compounds. These are called aggregates. Soil structure describes the way soil particles are aggregated. Soil structure affects water and air movement through soil, greatly influencing soil’s ability to sustain life and perform other vital soil functions.

Define soil aggregate: Soil aggregates are groups of soil particles that are bound to each other more strongly than to adjacent particles. Organic matter and mycelium “glues” the particles together.

Define (in relation to soil structure) macroporosity and microporosity: Soil pores exist between and within aggregates and are occupied by water and air. Macropores are large soil pores, usually between aggregates, that are generally greater than 0.08 mm in diameter. Macropores drain freely by gravity and allow easy movement of water and air. They provide habitat for soil organisms and plant roots can grow into them. With diameters less than 0.08 mm, micropores are small soil pores usually found within structural aggregates. Suction is required to remove water from micropores.

Growing Grapevines & Grapes

Why is it recommended to prepare a vineyard site (soil prep, trellis) before planting vines? Preparation of the vineyard site is very important since vineyards, once established, are maintained for many years. Correcting site imperfections and improving the site will add greatly to the longevity and productivity of a vineyard. Some activities (i.e., land levelling, drainage) can only be done prior to planting. Ideally, a vineyard site should be prepared at least a year or two prior to planting. Activities to prepare the site for planting include soil preparation, drainage, weed reduction, removal of wild hosts, deciding when to plant and determining what to plant. Trellising must be accomplished as it dictates vine and row spacing in the vineyard.

Why is it recommended to grow grafted Vitis vinifera vines? Vitis vinifera grapes are especially susceptible to phylloxera, so purchasing vines grafted to resistant rootstock is best in areas such as western Washington, where the pH is low and could lead to issues with the vine. If you want to grow a new varietal, you have the option of grafting cuttings onto your existing rootstock, saving you the time of establishing a new root system; if your original vines were planted on grafted rootstock designed to resist phylloxera, or if your current rootstock is designed to grow well in your type of soil and climate, you may wish to keep those already established roots and graft onto them.

When planting a vineyard, what climate and soil factors can impact what vine spacing to use? In-row vine spacing ranges from 3 feet to 12 feet, with 6 feet to 8 feet being most common. Spacing within the row will be determined by soil vigor potential, the climate in which the vines are grown, and the cultivar/rootstock combination. For example, use 8 feet to 10 feet between vigorous vines, such as those planted in deep, well-drained, fertile or irrigated soil. Use 6 feet between less vigorous vines, such as those planted in shallow soils. Closer vine spacing also complicates canopy management, but wide vine spacing can result in poor trellis fill. Therefore, a vine spacing of 6 to 10 feet is generally recommended for non-divided canopy training systems (e.g., VSP).

How can selection of trellis and pruning systems affect the microclimate around growing grape clusters (in general terms, you don’t need a long explanation)? Trellising and pruning systems determine canopy cover of vines and wind speed. This effects how much sunlight is hitting the grape clusters, which in turn effects temperature and humidity.

List reasons used to explain why grapevines should be pruned every year.

- Maintain vine form. In commercial grape production, vines are trained and pruned upright onto a trellis support structure. This enables the vine to retain a similar shape year after year in order to facilitate cultural operations including harvest.

- Regulate the number and positions of shoots on a vine, and cluster number and size. During pruning, one removes buds that would otherwise become new shoots, with new clusters in the spring. By regulating the total number of buds, one is concentrating growth into remaining shoots and clusters.

- Improve fruit quality and stabilize production over time. A given vine in each season can only produce a certain quantity of fruit. Its capacity to do so is largely dependent on the amount of leaf area and photosynthetic activity. By consistently limiting the number of shoots and leaves by dormant pruning, one is also working to produce the maximum crop without delaying maturity year after year.

- Improve bud fruitfulness by bud selection and placement.

Winemaking

Briefly explain why winemakers care about the temperature of fermenting grapes and how this may be controlled. Fermentation properties affect many chemical and physical properties of wine. Yeast prefers a temperate atmosphere; fermentation is an active, living process, and all that activity can cause temperatures to rise in your must. Ultimately, this means that to create good wine with the flavors you intend, it is extremely important to control must temperature. The type of wine you are producing will direct what temperature range is optimum. White wines are generally fermented under cool (not cold) conditions, while red wines can be fermented a little warmer. For a fruity, white wine, cooler temperatures — 40 to 70 °F (4 to 21 °C) — allow for the retention of highly volatile aroma components. A rapid, warm fermentation will create a draft of carbon dioxide rising from the must, taking fruity esters with it. However, red wines stand up much better to elevated temperatures (50 to 80 °F/10 to 27 °C), and extraction of color and tannins may be enhanced by it. Fermentation speed and temperature are directly related in that the higher the temperature goes, the faster the fermentation will roll. And the faster the fermentation goes, the faster the temperature will rise.

While it might at first seem advantageous to have the fermentation finish in just two days or so, consider how this will affect both the activity of the yeast and the flavor of the must. When fermenting at rapid rates, certain strains of yeast can produce hydrogen sulfide (H2S), giving your wine a rotten egg or cooked cabbage smell. On the other side of the coin, if a must is kept too cool, the fermentation will simply stop. The main danger here is that the must is then vulnerable to contamination by organisms that can better tolerate the low temperatures. With the yeast not producing alcohol, bacteria, wild yeasts, and mold can grow. The lower the temperature, the slower the fermentation will proceed. Molasses-in-January-type fermentations leave the must open to those other organisms and all the “characters” they produce. It’s best to get the fermentation started quickly and then keep it rolling at a nice, even temperature for the duration of the process. In commercial applications, wine is warmed by its own fermentation activity in an insulated container and cooled by glycol or ammonia jackets. Heat exchangers are used both to warm and cool must, juice, and wine.

Briefly discuss how wine is stored to maintain quality, what are optimal conditions? Wine is best stored in a dark and well-ventilated cellar, at a temperature between 55- and 60-degrees Fahrenheit, and 60 to 70 percent humidity. Basically, the bottles should be stored in a horizontal position, so that the cork always remains in contact with the wine.

Hypothesis.is challenge question

Contemplate a statement from Steve, “For fine wine sites, it’s not the soil and rainfall as individual factors, it’s the balance of soil drainage and water retention that makes moderate amounts of water available to grapevines.” Based on Wine and Place (pages 77-83 excerpt from Gerard Seguin, “’Terroirs’ and Pedology of Wine Growing’”), cite pieces of evidence for Gerard’s argument that regardless of the year-to-year variation in annual precipitation each site gets, sites that produce fine wines year-after-year share the characteristic of having moderate soil water availability from budbreak until veraison, and decreasing water availability until harvest.

•#1d: Case Study Tasting Research: Wine

This week we had the opportunity to view an interview by Dr. Sarah Williams of Luke Bradford, former Greener and owner/operator of COR Cellars in Lyle, Washington.

https://www.corcellars.com/

Image by Sarah Dyer. Photography from TripAdvisor.

Luke’s Story (1-13 min): Take notes as you listen such that you are able to use your notes to re-tell Luke’s story from Evergreen student to owner/founder of COR Cellars. Include your detailed notes here making sure to include information about how various but specific places, passions, tastes, and languages shaped Luke’s education and business decisions.

Luke was born in Manhattan, NY and raised in Pennsylvania and Utah. He was always an avid skier and mountaineer, which led him to looking at colleges in or near the mountains.

Evergreen was off his radar, but he ended-up falling in love with the school – the walk from F-Lot to the Evergreen beach won him over. A climbing trip to Italy in his Sophomore year changed the course of his life and revealed his passion for wine. Luke’s cousin owned a winery, and after spending the summer he knew that his future was going to be wine-centric. Luke was offered an independent study but chose to take a year off and work in Tuscany harvesting grapes. He then came back to Evergreen and built the entrepreneurial skills he would need to turn his passion into profit. After finishing his last two years at Evergreen, Luke went back to Italy for another harvest. Upon his return he got a winery job in the Gorge, the community felt right and felt like a place a new person could break in without letter of rec, as it were. He was attracted to the young and energetic business community around him and recognized the potential of a tasting room and destination wine business. In 2003 he started planting his 20-acre vineyard in Lyle, WA. It is now Luke’s 18th vintage at COR and he is 41 years old. Evergreen brought him to Washington, and though another school might have had a better program for viticulture or oenology, Evergreen jump-started his passion.

COR Wines and Luke’s Wine Tasting Recommendation (58-92 min): Type your response to each of the following prompts based on Luke’s talk.

Why did Luke choose the name “COR Cellars”? Be sure to include at least three ways that for Luke “COR” evokes a sense of place.

Luke chose the name COR cellars to embody his love of wine, mountains and people. COR is Latin word for heart and the core of etymology of all words pertaining to the body. The spirit of COR is quoted on the label — “Good wine pleases the human heart” — which Luke pulled from his time studying Latin at Evergreen. COR is about what makes your heart go and what makes up the Gorge’s vibrant energy. Additionally, the three letter Latin word leant itself to becoming a logo within itself, which Luke found attractive. COR is about the human spirit, or heart, as well as the mountains; Mt. Etna is an active volcano in Sicily, and Luke worked for a summer at a vineyard on its slopes; he describes it as a captivating area. He’s now working in mountains near volcanic land in Washington, developing COR, the heart of a human being and themselves emotionally, but also the volcano CORE.

Why does COR have two labels? Which AVA corresponds with which label?

In the first labels for COR, the O was a little off center. The new COR labels are now centered, but represent the same beautiful, mostly red wines from Horse Heaven. AGO — to live – is the redesigned label, and rosse and pinot gris, higher tier wines, corresponds with AVA AVA is American Viticulture Area – focused on Gorge AVA only, mostly white wines. The original COR label is mostly red wines from Horse Heaven. The higher tier wines have a new, AVA specific label called “AGO”- “to live” – and is located in the Gorge, WA AVA, producing white wines.

What are at least 4 recommendations Luke makes for a wine tasting at COR?

- Making appointments ahead of time and be on time.

- Allow yourself enough time: three wineries in a day are about right. However, be time conscious and courteous in the tasting room.

- Don’t wear a lot of fragrance, as it will make tasting challenging for you and others.

- Come curious and ready to try new and/or different things.

- Ask questions and be engaged!

What are at least 2 of Luke’s pet peeves?

- Wine know-it-alls.

- Aggressive, noisy swirling and spitting of wine.

- Licking the glasses.

What wines should you expect a tasting flight to consist of at COR and why?

In a tasting flight at COR winery, one might expect between 4 and 6 wines. It would begin with a sparkling wine, followed by 1 or 2 whites or rosso, light red, and then 3 higher tier reds. The composition of the flight will change with the seasons, with more whites in summer and reds in winter.

Compare and contrast the story of Luke’s favorite wine (at the time of the conversation) with the story of your favorite wine–or a beverage of your choice (balsamic or sipping vinegar, shrubs?).

Luke likes champagne or a white wine from Bourdieu. Both are celebratory and uplifting. He goes on to discuss how his favorite wines are tied to sense memories, times and places. I love fortified wines (particularly port), and my favorite was a white fortified wine from La Chiripada Winery & Vineyard in New Mexico Called Vino de Oro. It is a sweet Muskat wine fortified with oak aged brandy. I still remember tasting it for the first time, and I remember the faces of friends who drank it with me. It was the first fortified wine I ever tasted, and it’s still my favorite.

Would you be interested in participating in a virtual wine tasting with Olympia’s Wine Loft manager Justin Wilkes? Justin is willing to order a COR Cellars selection of wines (and/or cheaper equivalents) for T/M participants to purchase. Here’s a Thurston Talk article about Justin and The Wine Loft: https://www.thurstontalk.com/2017/03/22/the-wine-loft/

Yes please! I would love to have this experience!

•#1e: Stuckey’s Taste Book Experiments

The experiments done in this lab are all taken from Barb Stuckey’s book, Taste and adapted from the work of Caleb Poppe.

In this lab we walked through four experiments that focused on our own personal perception of how we taste the foods that we enjoy. Knowing that we all come from different cultures, heritages, and backgrounds, we too must know that these have a powerful effect on how our individual mind and body interact with the food we use to fuel them. With that being said, we all share common ancestors, and our bodies may have a lot more in common than we at first believe.

The Experiments

- “Taste What You’re Missing: 5 Minute Raisin D’etre” – page 347

- “Taste What You’re Missing: Your Taster Type” – page 30

- “Taste What You’re Missing: Separating Taste from Smell” – page 52 & 53

- “Taste What You’re Missing: Sour all Over” – page 53 & 54

1st: Taste What You’re Missing: 5 Minute Raisin D’etre – page 347

As Stuckey says at the beginning of this section: “we often take meals for granted…”, often rushing through the process of eating a meal and seldom slowing to eat at such a pace that allows us to stop and fully contemplate the meal and its entire story of how it made it to our mouths. In this experiment we went to the other extreme and went super slow-mo through the act of eating only 3 raisins:

We inspected each raisin and thought about how it came to look like that, having once been a plump and juicy grape. Once we put the raisin in our mouth, we held it there awhile and thought about where it came from (California soil). We tried to make all 3 raisins last 5 whole minutes!

1st Experiment Questions: (p 347)

Reflection: What were your thoughts and feelings during these 5 minutes? Was it pleasant? Was it tough? What did you appreciate?

I love raisins and dried fruit in general, so I really enjoyed this experiment. I enjoyed experiencing the leathery texture break down into a jelly-like consistency. I felt like I wanted to spend more time with this experiment, and I imagine trying it again on my own time, as a meditation on my own understanding of terroir.

What senses and tastes were being triggered for you while eating these raisins?

I have strong sense memories of my grandfather, who loved raisins and especially the California Raisins. I’m also reminded of disappointment on Halloween. They were pleasantly tangy, extremely sweet, with a tiny amount of acid and sourness. I loved the slight earthy smell of them, and their texture: squishy and dry at the same time.

Summarize the life you saw for the raisin before you watched the California Raisins ad.

I imagine that this grape was of low quality, as it wasn’t sold fresh or used as a wine grape. It was probably grown in California and probably industrially dried. Migrant farmworkers from Mexico and Central America probably picked it, to the profit of a large company.

Describe the life you see for the raisins that are now part of you in relation to “American” labor, branding, and advertising/entertainment.

The juxtaposition of my grandfather’s love of the California Raisins and their roots in Jim Crowe and white supremacy is jarring, and something that I am still dealing with.

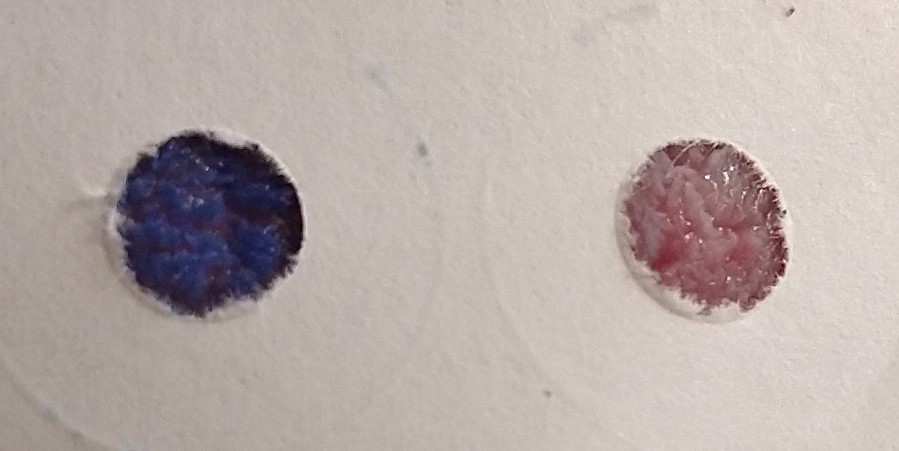

2nd: Taste What You’re Missing: Your Taster Type – page 30

In this experiment, we tried to better understand the topography of our tongue. It is safe to say that a whole range of factors attribute to how many tastebuds our individual tongues have, and while tastebuds only play a small role in our perception of taste, they are no doubt vital. Using the quetips that were provided to us, we dipped them into the blue dye, coating the entire cotton swab so that it is saturated, and dabbed an area on our tongues about the size of a nickel and placed the binder saver ring on the dyed area of our tongues. Using our phone or a magnifying glass, we tried to count the number of taste buds that fit inside of the binger saver ring. *It may be best to do this in front of a mirror so that you can see what you are doing*

In the book, we are given a key as to how we interpret the number of tastebuds we count in the binder ring – in its important to remember that these numbers are subjective AND there is no way to know if the binder savers we are using are they same width as the ones used in the book.

Photography by Sarah Dyer.

2nd Experiment Questions: (p 30)

How many tastebuds did you count within the binder ring?

I counted 53 or so taste buds in the binder ring. Oddly enough, I had an easier time counting them undyed.

Circle the result that applies to your count and reflect on how this count does or does not correspond with your experience of your taste sensitivity.

| ***Remember that we are not certain if the binder saver holes that we are using were the same size as the ones Stuckey used.*** |

0-15 = Tolerant Taster

16-39 = Taster

40 or more = ***Hyper Taster***

What are your thoughts on the role that tastebuds play in your tasting experience? (You may have a more informed answer for this if you wait to answer until the end of this lab, having played around with our sense of taste a bit!)

I’ve come to the conclusion that my taste buds take a backseat to my sense of smell in my tasting experience, and that memory affects my taste to a greater degree than I ever understood. Since childhood, I was always an adventurous eater, but certain flavor profiles were unbearable to me (mostly bitter and sour). I have acclimated to those flavors and grown to appreciate them, though the taste of a raw onion will never make me smile.

3rd: Taste What You’re Missing: Separating Taste from Smell – Page 52 & 53

We may all remember hearing at some point the line “…plug your nose, it’ll go down easier” maybe in reference to taking cough syrup as a child or eating overpowering, stinky foods. As we learned last quarter, the majority of how we perceive taste lies within the aromas that we inhale as we eat a meal; holding our noses closed greatly reduces the amount of aromas that travel into our nasal passage, the location where aromas are detected. In this experiment we tried to pick out what we are tasting when we ate very flavorful foods with our eyes and noses closed. Jellybeans are sweet, colorful, and packed with flavor, but how much of the jellybean were we tasting with our mouths and how much were we tasting with our eyes and nose?

From the jellybeans that we were provided, and with our eyes closed and our noses plugged, we picked a random jellybean, put it in our mouth and gave it a couple chews to release the flavor – then unplugged our noses and took a steady breath in, paying close attention to how this changed our perception of the jellybean. Could you tell what flavor jellybean you had chosen before you unplugged your nose? What specific senses of taste were being triggered? We cleansed our palates and repeated the experiment a few times.

3rd Experiment Questions:

What are the five basic tastes? Draw them onto your own version of Stuckey’s tasting star (image on first page of each chapter).

Image by Sarah Dyer.

What senses were triggered before and after plugging your nose?

When my nose was plugged I tasted primarily sweetness, often paired with a burning sensation. When I unplugged my nose, that burning sensation was often transformed into a sourness.

Could you tell what flavor jellybean you had chosen before you unplugged your nose? What flavors did you get?

I couldn’t really tell any flavor until I got either an orange or tangerine flavored jellybean. Something about the way it tasted, even with my nose plugged, was strangely recognizable. It felt like a certain dryness on my inner cheeks.

What went through your head at the moment of unplugging your nose?

I was so surprised by most of my jellybeans! I did definitely get the orange/tangerine flavor, but that was more of a mouthfeel than a flavor, I think.

4th: Taste What You’re Missing: Sour all Over – page 53 & 54

While some may argue that certain parts of our tongue are better equipped to identify certain types of taste (sweet, sour, etc.), it is rather easy to prove we can experience each of the 5 basic tastes on all parts of our tongue. In this experiment, we did just that. With the quetip and the vinegar, a highly sour/acidic substance, we swabbed our tongues in different locations and payed attention to where the sour flavor is most and least heightened. Do you recognize any correspondence with your vinegar swabbing and the map of the tongue on page 54?

4th Experiment Questions:

What did you find out about the map of your own tongue, in relation to the controversial histories of the supposed map of the tongue’s taste areas?

The classic map is such a fake! My tongue experienced the same sour flavor all-over. I did experience different intensities on the sides of my tongue (and cheeks?).

Did you experience different intensities in different areas?

I did experience different intensities on the sides of my tongue (and cheeks); I didn’t expect such a reaction from that specific area, so I was surprised.

What have you learned from these 4 experiments? How might your learning relate to any/all of the TM program questions regarding the taste of place?

I learned that I am a super taster, which was gratifying to know; I spent many years cooking professionally, trusting my taste buds, so knowing that I can back it up scientifically is good to know. My sense of smell has always been strong, almost freakish, and inherited from my paternal grandmother; my grandfather and I used to eat sardines together, but we were banished to the porch: absolutely no fishy tins in the house. I have the sudden wish to dye her tongue blue…

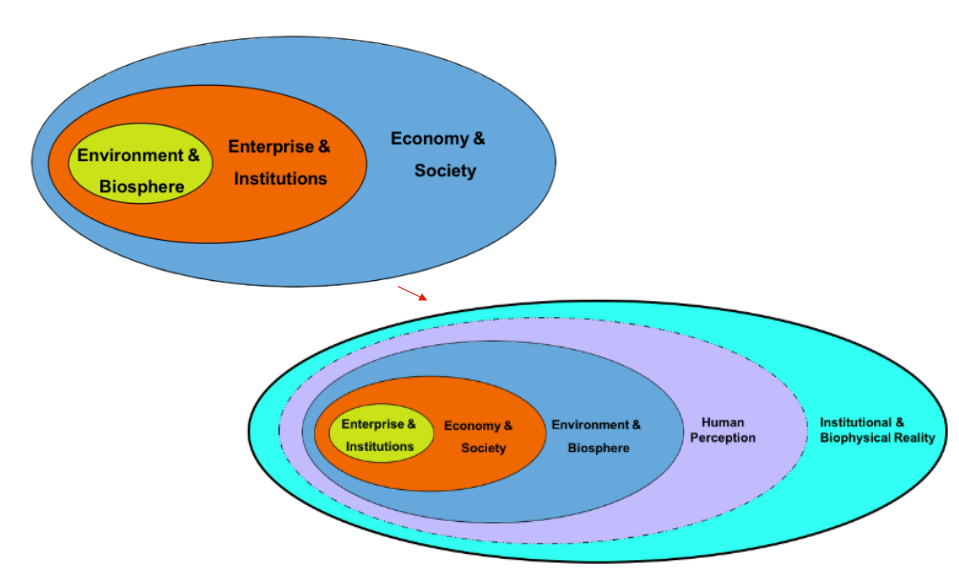

•#1f: Sustainable Entrepreneurship

As shared by Tamsin Foucrier.

Sustainable Entrepreneurship

I’ve begun calling week two of Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Futures for Food and Agriculture, “Aldous Huxley on Business”. I mean this with all due respect, alluding to the fact that the lecture this week cracked the doors of my perception a wee bit in relation to business, economy and capital enterprise.

We began with the ‘classic’ model of sustainability, the 3 P’s: Planet. People. Profit. In exploring this concept, we utilized a phenomenal infographic-style short film, which pointed-out the critical flaw at play in the 3 P’s, namely that each circle within the diagram is the same size, which implies equal importance or value. This, of course does not reflect the biophysical realities of our world. Instead, we find ourselves working toward a nested image in which business and society are embedded in nature, as everything exists in nature at some point.

With our newfound understanding of the failures of the 3 P’s approach to sustainability, we began to explore the current reality of our economy. This reality asserts that enterprise and society has control of the environment, a reality in which a tree only has value based on the goods and services it can produce, in which no inherent value exists in the environment and its only value exists in its capacity as a commodity to be bought, sold and traded by the marketplace.

Designed and presented by Sustainability Illustrated via YouTube.

As Tamsin put it, these narratives and assumptions are “baked into our bones”, and so we are challenged to “move beyond ” and reimagine what business can be. This shift involves an understanding that we exist in an environment bigger than ourselves and have developed our economies, societies, enterprises and institutions. We are bound by the limits of our environment and biosphere.

So, bound by the limits of our human perception and our historical assumptions surrounding business, enterprise, and capitalism, we as budding sustainable entrepreneurs might feel quite limited in our ability to innovate and think-through old paradigms. We are left with two ideas two guide and shape our understanding of these models. One: We are governed by biophysical realities which CANNOT be changed by our perception. And two, sustainability in enterprise and business involves reshaping our understanding of how these nested circles relate and interact, how they have done so in the past, and how they might in the future.

Image by Tamsin Foucrier.

In truth, I am cynical of capitalism or any other system that commoditizes the basic needs of people and the environment. If food is a right, if water is a right, if housing is a right: how can we justify talking about markets, premium products or value editions? How can we prop ourselves up on a system that is so broken and that has failed so many? My experiences and assumptions weigh heavily, but I will leave the door of perception open just a crack to let in the hope that a functional, sustainable and equitable system can exist and that I will live to see substantive change in my lifetime.

•#1g: Climate and Resilience Event Series/Seminar

•#1h: Foodoir: Your Story of Tasting Place

“(That was an excellent restaurant; a rather small room with paneled walls and comfortable chairs and old but expert waiters. It was in the Union Station, I think. I want back years later, and found it had a good wine list and a good chef. It was like coming full circle, to find satisfaction there where I first started to search for it.)

“Anything,” I said, and then looked at my uncle, and saw through all my gaucherie, my really painful wish to be sophisticated and polished before him and his brilliant son, that he was looking back at me with a cold speculative somewhat disgusted look in his brown eyes.

It was as if he were saying, “You stupid uncouth young ninny, how dare you say such a thoughtless thing, when I bother to bring you to a good place to eat, when I bother to spend my time and my son’s time on you, when I have been so patient with you for the last five days?””

M.F.K. Fisher, The Gastronomical Me, Page 34

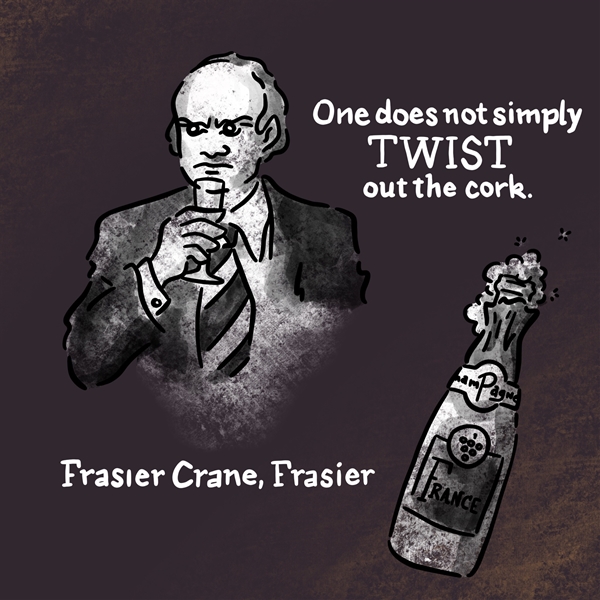

Hail Corkmaster, The Master of the Cork! or Wine and the T.V. Sitcom Frasier

Image by Cellars Wine Club.

Confession: I’ve been obsessed the sitcom Frasier since high school; it didn’t have any cute boys in it and everything was very beige, but it lit-up my imagination. Its full of cultural references, which were enriching for a teenager growing up in a rural Alabama town. I didn’t get all the references, the French quotations, or the many hints at terroir, but as I got older, I picked-up on more and more of it.

It was a sitcom deeply invested in art and culture and music. It loved its high brow references and allusions. And it trusted the audience, even a fourteen-year-old, to be able to understand them. But beyond that, it always made sure to deflate the pompous and snobbish attitudes of Frasier and Niles.

From Frasier

“Sherry, Niles?”

Frasier always has a decanter of the Spanish fortified wine located between his kitchen and his grand piano. Just about any time Niles walked in the door, Frasier would, after greeting him, invite him in for a drink.

The iconic line. The question in almost every episode, a brilliant physical use of space and motion to carry conversation and set a mood. It is a stuffy drink for old ladies, which is exactly why it became their regular drink over a mere glass of wine. Sherry is very old world; its fitting this is the iconic drink of Frasier, a character who basically huffs western culture.

And in that way, it deflated the mystique of things like the opera, theater, museums and fine dining. Nothing defeats the purpose of art more than making it the exclusive domain of the right-kind-of people. By undermining Frasier’s elitist attitude (and the attitudes of people like him) the show attempted to make these cultural institutions more accessible.

From Frasier, Season 8: Episode 18

Wine was easily incorporated into the show because both Frasier and Niles Crane were highly educated (Harvard and Yale graduates), sophisticated, hedonistic and pompous high society characters. Notably, Frasier and Niles are part of a stuffy Wine Club that features in various episodes throughout the series, exposing the audience multiple times to the basic terms and concepts of oenology.

Frasier Crane often waxes poetic about French AOC’s like Châteauneuf-du-Pape and Côtes du Rhône, and his brother, Niles, is always right there with him. In Season Two, the brothers open a short-lived French restaurant with a wine focus, and in the seventh season the brothers battle in a blind tasting for the title of “Corkmaster.” The snobbish brothers even once diagnosed Frasier’s producer, Roz, as having below-average intelligence because she “ordered a bottle of white zinfandel!”

From Frasier, Season 3: Episode 22

Wines are a part of the backdrop of the show almost constantly. Also, while Frasier was set in Seattle, Washington, I’ve yet to recognize a single time were Washington wines are mentioned. The world’s largest winery (E&J Gallo, including its Andre Cold Duck sparkling wine) was mentioned, but these were used more as sarcastic remarks. However, the characters did talk about Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, Loire (all French), and their beloved Sherry (Spanish).

From Frasier, Season 7: Episode 17

I am still picking-up on things from Frasier that I didn’t notice or understand as a kid. I recently learned that Frasier’s beloved French restaurant, Le Cigare Volant, shares a name with a wine produced by Bonny Doon Vineyards. The bottle has an interesting label and a fantastic story that is actually rooted in truth.

Tweeted by Bonny Doon Vineyard

As the story goes, a few Frenchmen started to see flying cigars after drinking far too much wine. As time went on, more of them started to see funny things in the sky. They got scared, as they felt those flying cigars would be interested in their wine/grapes, and might steal them. They went so far as to complain to their politicians and local governments, and while the local governments knew those who worried about flying cigars were crazy, they also knew wine was a large part of their culture and the local economy. So they passed ordinances against flying cigars and threatened the immediate impound of any flying cigars caught landing in the vineyards. The law was considered a success as no flying cigars ever landed in or near Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Le Cigare Volant literally translates to “The Flying Cigar”, but it also means “The Flying Saucer”.

How Frasier Would Shelter in Place During the Coronavirus

Frasier Online Oenophile Lexicon Explained

•#1i: Bibliography

COR CELLARS, www.corcellars.com/.

Daniels, Sarah E. “Climate Change Is Rapidly Altering Wine As We Know It.” Wine Enthusiast, 26 Mar. 2020, www.winemag.com/2020/02/03/wine-climate-change/.

Fisher, Mary Frances Kennedy, et al. The Gastronomical Me. Daunt Books, 2017.

Foucrier, Tamsin. “Introduction to Sustainability.” Zoom. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Futures for Food and Agriculture, 17 Jan. 2021, Olympia, The Evergreen State College.

Frasier. Created by David Angell, et al., NBC.

Grapes. “Vineyard Design.” Grapes, 20 June 2019, grapes.extension.org/vineyard-design/.

Gross, Liza. “Clues From Wines Grown in Hot, Dry Regions May Help Growers Adapt to a Changing Climate.” Inside Climate News, 23 Dec. 2020, insideclimatenews.org/news/02012021/wine-climate-vineyards-california-vintners-drought/.

Jacobsen, Rowan. American Terroir: Savoring the Flavors of Our Woods, Waters, and Fields. Bloomsbury Press, 2013.

“Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.” Preparing for Planting the New Vineyard, www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/crops/hort/news/tenderfr/tf1802a1.htm.

Moulton, Gary, and Jacqueline King. Growing Wine Grapes in Maritime Western Washington.

“Natural Resources Conservation Service.” NRCS, www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/site/national/home/.

Network, UCS Science. “Climate Change and Wine – Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty?” Union of Concerned Scientists, 16 July 2019, blog.ucsusa.org/science-blogger/climate-change-and-wine.

Patterson, Tim, and John Buechsenstein. Wine and Place: a Terroir Reader. University of California Press, 2018.

Reichl, Ruth. July 3. “Ruth Reichl on M.F.K. Fisher’s Lifetime of Joyous Eating.” Literary Hub, 2 July 2019, lithub.com/ruth-reichl-on-m-f-k-fishers-lifetime-of-joyous-eating/.

Roach, David and Warwick Ross, directors. Red Obsession. RED OBSESSION Documentary of China, Big Business & Wine w/ Dir. Warwick Ross, YouTube.com, 11 Sept. 2013, www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UBu_ho48cQ.

“Soil Quality Indicators.” Soil Quality Physical Indicator Information Sheet Series, USDA, www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_053261.pdf.

Stuckey, Barb. Taste What You’re Missing: the Passionate Eater’s Guide to Getting More from Every Bite. Free Press, 2012.

Triple Bottom Line (3 Pillars): Sustainability in Business, Sustainability Illustrated, 8 Apr. 2014, youtu.be/2f5m-jBf81Q.

“What Makes Great Wine… Great?” Wine Folly, 26 Nov. 2018, winefolly.com/deep-dive/the-science-behind-great-wine/.

Leave a Reply