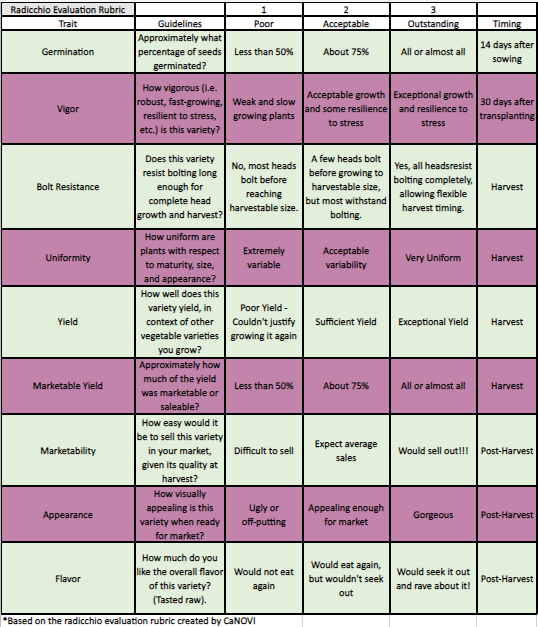

Held on October 6th, 2022 for the undergraduate program, Forest, Farm, Shellfish Garden: Experiential Learning

IMPORTANT RESOURCES FOR OUR RADICCHIO TASTING

to try after evaluating the raw radicchio.

Image by Sarah Williams.

Image by Culinary Breeding Network.

WHAT IS RADICCHIO?

Radicchio is a type of chicory that was bred for a heading, leafy morphology. Often mistaken for colorful lettuce or red cabbage, it is a cousin of endive, and is botanically related to both the dandelion and the daisy. Radicchio is often called Italian chicory because of its prominent position in Italian cooking, and the vegetable frequently appears in recipes including salads, soups, risotto, pasta, and pizza. Most varieties of radicchio are named after the Italian region in which they are traditionally grown.

WHAT DOES RADICCHIO TASTE LIKE?

Radicchio has a sharply bitter, spicy flavor, especially when eaten raw. While some people find this distinctive bitter taste challenging, there are ways to soak, cook, and/or balance the bitterness out of radicchio.

RADICCHIO IS EASY TO PREPARE IF YOU UNDERSTAND HOW TO BALANCE FLAVORS

Before using, trim any brown off the stem and remove the limp outer leaves. Radicchio is prepared like lettuce or red cabbage depending on the variety.

- Soaking: Radicchio owes its characteristic bitterness to naturally occurring chemical compounds released when the vegetable is cut or chewed. However, because these bitter compounds are water soluble, you can tone down the bitterness by soaking the cut leaves in water. To mellow the bitter flavor of raw radicchio significantly, soak the chopped pieces in very cold water for about 30 minutes before tossing into a salad. Radicchio is wonderful when utilized as a salad green, but it is worth bearing in mind that a little goes a long way. In a leafy salad, radicchio should be used to provide a pop of color and a burst of flavor.

- Balancing Flavors: Radicchio is often paired with sweet, acidic, or salty ingredients to “soften” the bitterness and create a dish with balanced flavors. Because this bitterness can be intense, pairing radicchio with the proper complimentary ingredients is key. Acidic foods like fresh citrus juice, briny items like olives or capers, sweet pairings like honey, figs, and stone fruit, or fattier ingredients like olive oil or bacon counterbalance the bitterness of the radicchio, creating interesting but harmonious flavors. In turn, radicchio’s bitterness can help balance other flavors, particularly in salads that contain rich ingredients, such as cheese, nuts, or fruit.

- Cooking: The bitter flavor of radicchio is most tamed with proper cooking. Potent flavor compounds in the radicchio break down, unearthing a softer side with an underlying nutty sweetness. The degree to which radicchio is cooked affects how much its taste changes.

- In Italy, the colorful vegetable is often sautéed then added to pasta dishes, risotto, and stews to balance the richness.

- Roasted or grilled wedges are a tasty side dish on their own or can be added to other dishes like pasta, risotto, or pizza.

- Radicchio can also be sautéed or braised, much like cabbage, and served as a side or stuffed into poultry.

Culinary Breeding Network

The mission of the Culinary Breeding Network links growers and eaters in a quest to add radicchio to the agricultural landscape of the Pacific Northwest. The goal of the Eat Winter Vegetables project is to increase production and consumption of eight winter vegetables in the Pacific Northwest, including radicchio. The project focuses on high quality varieties that have proved to have good yield, winter hardiness, storability and market potential in past vegetable variety trial research projects. The Sagra del Radicchio focuses in on radicchio and its place in the PNW agroecosystem and food culture.

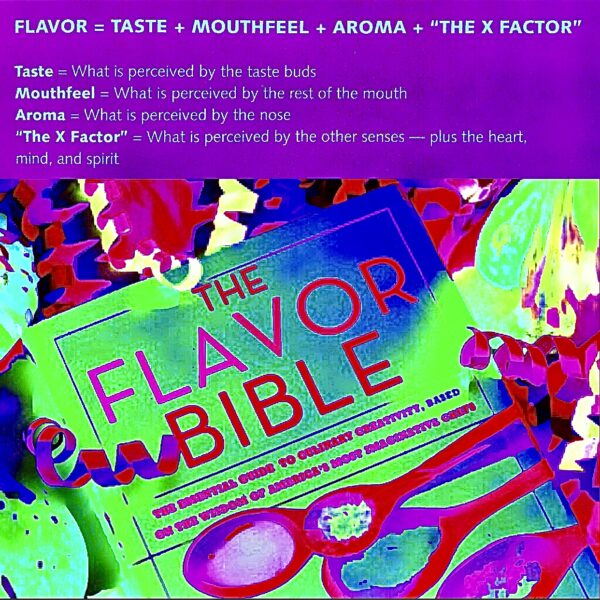

A FEW NOTES ON FLAVOR

Before participating in a tasting, it is important to understand how you experience flavor. Flavor as described by The Flavor Bible is a combination of taste, mouthfeel, aroma, and “the X factor”. Taste is what is perceived by the taste buds: salty, sour, sweet, bitter, and umami. Mouthfeel means temperature, texture, piquancy, and astringency. Aroma is about aromatics and pungency. “The X factor” accounts for memory, and other physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual factors.

TIPS FOR PARTICIPATING IN A TASTING

- Before you eat the food, use your other senses. Take a moment to jot down notes on appearance and aroma.

- Write down your first impressions…and your second impressions. As the tasting progresses, you may go back, re-taste a sample, and change your ratings. Reflect as you go.

- Eat a small portion of of the food, roll it around in your mouth as you chew. You can either swallow the food or spit it out. After doing so, suck air into your mouth and nasal cavity. Pay close attention to the flavors and aromas that appear when you complete this retro nasal breathing activity.

- Cleanse your palate between items. When tasting, drinking a bit of water between varieties can prepare and freshen the palate.

COOL RADICCHIO RESOURCES (NOT REQUIRED, BUT NEAT)!

- Climate Justice Academy with Professor Lane Selman & Radicchio Tasting with Caleb Poppe

- Culinary Breeding Network:

- RAD TV

- CBN Press Page

- “A Chicory to Dismantle Late-Stage Capitalism” by Kristy Mucci (Heated, 2020)

- “The Best Winter Greens Aren’t Green—They’re Pink” by Heather Arndt Anderson (Sunset, 2019)

- “The Age of Radicchio Is Upon Us” by Leah Koenig (Taste, 2019)