Wk 9: Crunch Time!

Final Dye Baths

Bracken fern

Horsetail

Alder cones

Marigold

This week was a big crunch to finish up my remaining dye projects that were in progress. The first project to tackle was the wool scraps that I would dye with my foraged material from Week 4. I had frozen and stored most of these items, but I went out to get some of them fresh as well (particularly the bracken fern and horsetails). I had multiple dye baths stewing on my stove at a time, it felt really nice to be so motivated and to get all of them finished so quickly. I used a mix of the all-in-one and the hot dyeing method for the wool; I will say that the all-in-one resulted in lots of plant material getting caught in the final pieces that took some patience to pick out.

Bracken fern

Horsetail

Alder cones

Marigold

These photos really do no justice to the final colors of these wool pieces. While the horsetail and alder cone dyes didn’t have much of an impact, the marigold and bracken fern created some incredible results that I’m pretty excited about. I think this part of my project, especially, taught me the important lesson of what works and what doesn’t work, and also that testing dyes out in advance is a great idea. I would love to expand on wool dyeing in the future, maybe focusing on spinning my dyed wool or felting with it as well.

Bracken Fern Dye – Curtain Disappointment

This curtain was a huge dyeing failure and disappointment. I had wanted to dye it using the remainder of my bracken fern dye because of the beautiful green color it had translated into the wool, but it wasn’t until the curtain was simmering away in the dye bath that I realized it was most definitely made from a synthetic fiber. This is an issue when dyeing because synthetic fibers, like polyester, are made from plastic materials that are unable to soak up dyes. Hence, my curtain did not dye. It was unfortunate that the tag on this curtain had been cut off or this issue could’ve been avoided, but I also probably should’ve known from feeling the fiber itself. Oh well. Lesson learned!

Marigold Dye – Bandana

Caleb Poppe was very kind in gifting me some dried marigold flowers to use for natural dyeing! I used some of the flowers in my shoe dyeing project, but I wanted to do something special with the rest of the flowers, not just dye a scrap of wool. So, I searched around for some ideas and settled on dyeing a white cotton bandana. I first mordanted the bandana with alum and then folded it up in a spiral pattern so that the piece would be tie-dyed instead of just one solid color. Then, I simmered the bundle in the marigold dye for an hour before letting it sit overnight.

It worked! I was so excited when I unfolded this finished piece, I think it looks so cool and I am so happy with the spiral pattern and the finished color. I finished the dyeing process by rinsing and washing the bandana before letting it hang to dry. This dye was such a success that I even saved some of the excess for later use. I am hoping to maybe try solar dyeing with the rest of it or another small tie-dyeing project.

Thank you Caleb for gifting me the dried marigolds!

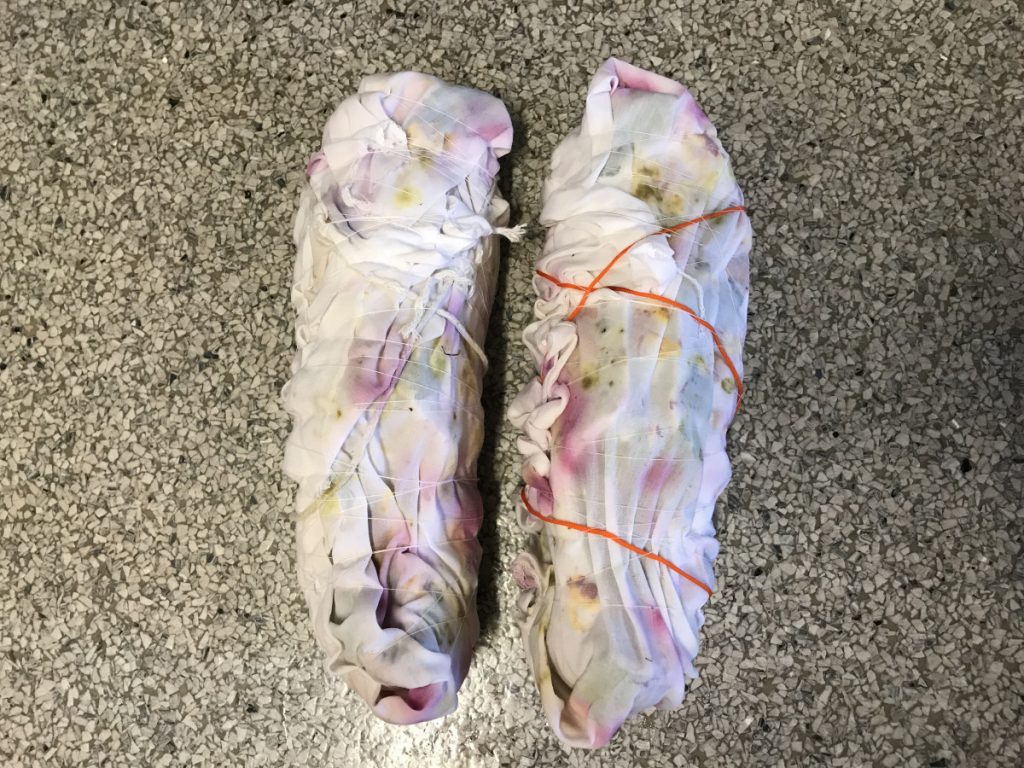

Final Shoe Update

This is what the shoes looked like after another week of bundle dyeing. I was a lot happier with the color variety, but still not 100% content with the final product. However, I chose to be finished with them at least for now so I could have something to share for this project. I still think the results are super exciting and I can’t wait to show them off around town!

I think once my presentation for class is over, I might do a final round of bundle dyeing with them to try and get a bit more color. I have found that the keys to bundle dyeing are time and patience. I think that the longer the dyer lets the bundle sit, the better the colors will be, but I was just overly excited and impatient so I chose to unfold them after a week both times around. Now that I understand this, I want to strive to be more patient so I can hopefully achieve even more colors in this project. I also think, though, that this project is really cool because I have the ability to come back to it whenever I want and try re-dyeing with whatever materials I want. Even if the current colors start to fade away over the summer, I can just simply re-dye with a new variety of materials, which is something I am pretty excited about.

Wk 8: Research

The end of Week 7 and the beginning of Week 8 were especially tough mental health-wise for me. Anxieties and stress were keeping me awake at night, leading to sleepy and unmotivated days of work. I was also visiting home for the beginning half of Week 8 which made me decide that maybe this was a good time to go back to my notes from the rest of the quarter and compile them into one big Week 8 post. I had (and was still acquiring!) notes from different films I had watched on natural dyes, along with notes from my book resources as well. This week highlights these gatherings and learnings.

Natural Dyes of Antiquity

A dye of any kind is created through the use of a chromophore or chromogen, which is a chemical compound that brings out color. In order for this color to stick, it must be caught tightly in the fiber, meaning that it is resistant to washing or fading from light exposure. Dyes can either bind to the surface of the fiber with the aid of a mordant (alum, iron, copper, and tin are common historical mordants) or the dye can be trapped within the fiber, which happens due to oxidation-reduction reactions and does not require the aid of a mordant. A good example of a dye that gets trapped as opposed to bonded would be indigo.

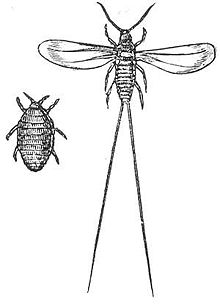

Ancient Reds

The most common chromophore used to create the reds of antiquity was the anthraquinone chromophore and its hydroxy derivatives, which may also be known as alizarin. This chromophore is the most stable and resistant to fading from light exposure and was most commonly derived from parasitic insects or the roots of plants in the Rubiaceae or madder family. More specifically, the dye would be harvested from the eggs of female Kermes vermilio insects or from cochineal insects. The harvest seasons for the eggs would occur whenever the eggs displayed the highest content of dye. Anthraquinone red dyes were considered a luxury good and were commonly imported, as well as locally found.

Another commonly used red dye of antiquity was the bark from redwoods. This dye was not as stable as the anthraquinone chromophore, but it was much more affordable for the public. It could also be used as a paint, as well as in cosmetics.

A final red dye of antiquity was the flavytium/anthocyanin red. These colorants are water-soluble and responsible for the red and blue colors of certain fruits and flowers. They were commonly used in illustration and paintings as a watercolor because of their range of colors between red and blue, but with only natural flavylium dyes, this range is limited to yellow and red. A commonly known flavylium red dye could be found in dragon’s blood resin, which can be extracted from trees of the Liliaceae family. Not only does dragon’s blood contain red chromophores, but it also contains additional flavonoids and steroids that make it suitable for medical, along with artistic, purposes. One medical use for dragon’s blood resin was in traditional Chinese medicine.

Ancient Blues

Indigo blue is one of the oldest and well-known dyes of history. It is very light-stable which explains its popularity and longevity as a colorant. In ancient times, indigo was highly prized for its quality, but this made it very expensive to transport and access. Indigo is a vat dye, meaning one or more carbonyl groups are present within the dye. This also means a mordant is unnecessary for fixing the dye to the fiber.

Another blue dye of antiquity is anthocyanin blue, which can be extracted from cornflower. However, this blue is tricky to capture because of the complexity of its structure. Also, once the color is captured, it will only be stable in concentrated solutions. If diluted, it will rapidly lose its color.

Ancient Purple

The color purple throughout history has been a symbol of high status and royalty. Across different cultures and religions, the color was used to mark status; Persian monarchs even made purple the official color of royalty in the 9th century BC. Purple was also a sacred color, as it was the color of the sacrificial mantle used by Christ.

Tyrian purple, the first true purple, was always the most expensive dye in the market. It was procured from Mediterranean shellfish, specifically those of the genera, Purpura. The dye was found in secretions from the hypobranchial glands of the gastropod mollusks. Evidence of this work could be found in the piles of shells leftover on beaches around the Mediterranean.

Ancient Yellows

There are so many sources for natural yellow dyes, even in nature today. Yellow dyes, however, are less resistant to fading than a red or blue dye, which means many yellow antique pieces we view today probably look a lot different than how they looked when they were first dyed. Flavonoid yellows, which are commonly used for dyeing, come in two different groups. The first group consists of the chromophores apignen and luteolin, which are found in plants as glycosides. Luteolin is one of the most stable yellows, making it a common choice for dyeing. An example of a plant that luteolin can be found in would be weld.

The second group of flavonoid yellows consists of flavonols which contain flavonoids. These flavonoids are well known because of their antioxidant properties, an example being quercetin. Plants within this category of flavonoid yellows include onion skins, dyer’s greenwood and chamomile, marigold, and yellow wood.

Another ancient yellow dye is carotenoid yellow. Carotenoids can be found in many foods we might eat each day, including the red of tomatoes and the orange of carrots. The most popular carotenoid yellow used in ancient times was golden saffron yellow. Two final ancient yellow categories, chalcone and aurone yellows, are similar to carotenoid yellows because of their ability to absorb light at longer wavelengths, resulting in more golden and orange-y hues as opposed to true yellow tones.

Natural Dyeing of Japan

In Search of Forgotten Colours – Sachio Yoshioka and the Art of Natural Dyeing

“The colors you can obtain from plants are so beautiful. This is the one and only reason I do what I do.”

-Sachio Yoshioka

Sachio Yoshioka works with natural dyes in Kyoto, Japan. He has devoted 30 years of his life to the art of natural dyes, hoping to revive forgotten natural dyeing traditions from Japanese culture. In the Yoshioka dye workshop in Kyoto, dyers work with safflower and purple gromwell to create ancient colors used in traditional Buddhist ceremonies, including the Omizutori ceremony that welcomes the start of the spring season. Safflower, which creates a Beni Red, has a particularly complex dye extraction process; it’s a miracle that dyers of the past were able to create such a wonderful color through such an interesting process. Beni Red is used for painting paper that is folded into beautiful flowers for the Omizutori Buddhist ceremony. The Yoshioka workshop has the honor of creating and delivering this hand-dyed paper each year for the festival.

This video was extraordinarily beautiful to me. The imagery of the Yoshioka workshop paired with the beautifully dyed pieces of silk was very welcoming to the eye; the videographer really knew how to draw in their audience with the right shots. The lack of speaking within the video also brought around a certain calm that created a peaceful mindset while watching. The one spoken quote by Yoshioka, himself, also stood out because of the otherwise speechless movie, highlighting the quote’s significance and power. Finally, I loved the glimpse into traditional Japanese culture shared within this video. The imagery of the Buddhist ceremony was incredible to witness and changed the natural dyes from just an enjoyable project to a tradition full of culture and wonder. Yoshioka’s dedication to traditional natural dyeing techniques is beautiful and inspiring. His passion is wonderful to behold.

“Successful dyeing requires intimate understanding of the effects of temperature and dye concentration. How the thread or cloth is dipped is also very important.”

Natural Dyeing of Peru

Made In Peru | Natural Dye

“We work to live, not live to work.”

This video highlighted the work of Ricardo Galmed, an economist at the National Agrarian University in Peru who also operates a dye house with two other dyers. After conducting studies surrounding their use of cotton, they found that there was no point in using synthetic dyes, especially since Peru is so rich in natural dyes to use. The three main natural dyes that Galmed works with in his studio are cochineal for red, indigo for blue, and peppercorn tree berries for yellow. Through using these three primary colors, Galmed is able to create a whole rainbow of naturally dyed cotton articles.

I loved seeing the contrast between Peruvian and Japanese attitudes around natural dyes. In Japan, there was a lot of culture and tradition surrounding the art of natural dyeing, while this Peruvian story was just the side project of a university economist. I think this video really highlighted the fact that a person doesn’t have to dedicate their entire life to natural dyeing in order to partake in it and create beautiful pieces through it. While the passion and dedication of Yoshioka in Japan was highly inspiring and wonderful to witness, Galmed shows that this practice is able to be done by almost anyone, while still celebrating the specific qualities that separate countries and locations bring to this art style. Galmed prompted viewers to make their own textiles and natural dyes through everyone’s individual traditions, which was a beautiful message to share. Despite this difference, I still found this video to be equally beautiful in its imagery and making, and I liked the visual similarities between the workshops and dyeing processes in both Japan and Peru.

A final note about this video is that it was a video produced by a clothing brand, Alternative. I wanted to note this because of the bias that may be present and resulting in the differences I have noted between Peruvian and Japanese natural dyeing. This story was shared in a much briefer fashion; I wish there had been more to see to get a fuller picture of the similarities and differences between these two cultures.

Natural Dyeing of Australia

Captured by Color: Introduction to Natural Dyes

In Bedfordale, Australia, Trudi Pollard works to create beautiful pieces of art using natural dyes from her kitchen and also grown on her own property. She emphasizes the importance of not letting food go to waste, sharing how onion skins, used tea bags, even the stalks of broccoli can be used to naturally dye a variety of different fibers. Pollard shares her personal tips and tricks for dyeing, including her method for determining if dyes are the desired color and also how different pots (stainless steel vs. copper) can help produce different dyed results. Pollard also shares a variety of different dyeing methods within this video. The first method is called sun or solar dyeing, where the fiber is placed in a jar with the dye bath and dye material and left out in the sun for a few days or weeks until the desired color is obtained. The next method is the use of any rusted materials, such as nails, horse shoes, and gears. These items are laid out on the fiber, dampened with water and lemon juice and sprinkled with salt before getting wrapped in plastic and left to soak in the sun. The results of this method are particularly beautiful, but the safety of using rust in a dyeing project is not addressed at all. Finally, Pollard discusses eco printing, which is very similar to the bundle dyeing method.

Overall, this video was really beautiful and fun to watch. Getting to hear these tips and methods from a professional natural dyer was really cool and inspiring. Pollard’s final pieces are also exceptionally beautiful, unlike any naturally dyed pieces I have encountered elsewhere in this project. Pollard makes naturally dyeing a more accessible project for everyone, laying out a variety of different methods that are fairly simple for anyone to try at home. Her emphasis on not letting food go to waste and on using plants grown naturally on her property is also a beautiful lesson. I am now inspired to try a variety of different dyeing methods, especially the solar dyeing and eco printing methods.

Chemistry of Natural Dyeing

The Chemistry of Natural Dyes – Bytesize Science

This video features the Textile Arts Center in Brooklyn, New York. It shares some of the basic chemistry behind natural dyeing through the use of red cabbage, a substantive dye, and cochineal, an adjective dye. Substantive dyes contain the anthocyanin pigment which is water soluble. This makes it so that the dye is able to attach to the fiber on its own, without the aid of a fixative, or mordant. Adjective dyes, on the other hand, do require a mordant to fully bond to the fiber.

Another area of dyeing information that this video shared was on the use of modifiers, specifically related to substantive dyes like red cabbage. The pH of the anthocyanin pigment directly relates to what color the dye will produce. The red cabbage dye on its own produces a wonderful purple color, but when the pH decreased, becoming more acidic through the use of lemon juice, the dye became redder. In the opposite direction, when the pH became more basic through the use of baking soda, the dye turned a more blue-ish green color.

I really appreciated this video and its ability to lay out the complicated chemistry behind natural dyes in a simple, easy-to-understand way. While the chemistry illustrated in this video was very basic, I still found it very informative and helpful for the purposes of this project, and a lot easier to decipher than the writing in my natural dyes textbook. The demonstrations in the video were also helpful and accessible to anyone interested in this process, as the dyer shared many different options of natural dye materials, highlighting items that can probably be found within your kitchen right now. Finally, this video cleared up some other questions I’ve had about the dyeing process, specifically questions surrounding why fibers must be pre-wetted before dyeing, and also why a pH neutral soap is important to use when washing a final dyed piece.

Dyeing with Indigo

Indigo – From Fresh Leaves to Powder

“I like to be a part of the process.”

This video shared the process of working with the indigo plant to extract a beautiful indigo pigment for dyeing. It focused on the fermentation method for dye extraction, which uses the summer’s heat to ferment indigo plants in a vat of water. After a few days when the vat starts to get smelly, the plant material can be removed and lime (for increasing pH) plus oxygen can be added in order for the indigo pigment to sink to the bottom of the container. Once the pigment has fully separated from the water, the water can be carefully scooped out, leaving the sludge of pigment at the bottom. The dye can be used in its paste form, or it can be dried out in the sun to form a powder. The powdered indigo will store a lot longer than the paste will. This fermentation extraction process will create a darker blue than other indigo extraction processes; a truly beautiful ocean color.

While I did not work with indigo during this project, my mom recently purchased a few indigo plants that I am excited to experiment with in the future. The color created by indigo is exceptional, and I think the process explained in this video is really interesting and worth testing out. I like the idea of working with powdered natural dyes, instead of just creating a dye bath with plant material. I also especially liked this video because of the above quote, “I like to be a part of the process.” This quote referred to the hand grinding of the dried indigo paste to create the dye powder, which I thought was a beautiful connection to the creation of the pigment. Natural dyeing creates such a special connection between the fiber and the dyer, knowing your hands played a role in creating the beauty of the piece. I feel deep connections with each of the pieces I have dyed, and I think this quote highlights the specialness of this connection.

Dyeing with Mushrooms and Lichens

Natural Yarn Dyeing with Mushrooms and Lichen

I was really interested in using mushrooms and lichens as natural dyes, so this video was especially exciting to me. It went over dye extraction processes for the dyer’s polypore mushroom (phaeolus schweinitzii) and the rock tripe lichen (umbilicaria). For the dyer’s polypore, the process includes dehydration and grinding of the mushrooms into a fine powder, which can then be used as a dye when added to water. The dyer’s polypore creates a wonderful mustard yellow color, perfect for yarn or other fiber projects. For the lichen, ammonia will be used to extract the dye. This extraction process can take up to 6 months, but produces a lovely magenta color when used as a dye.

While I did not end up using any mushrooms or lichens within this project, this video left me inspired to experiment with these natural dyes in the future. The peacefulness of this video was relaxing; there was only soft music with video visuals and captions instead of speaking. I found these dye extraction processes especially interesting as well; I am inspired now to test out different extraction processes apart from just creating simple dye baths.

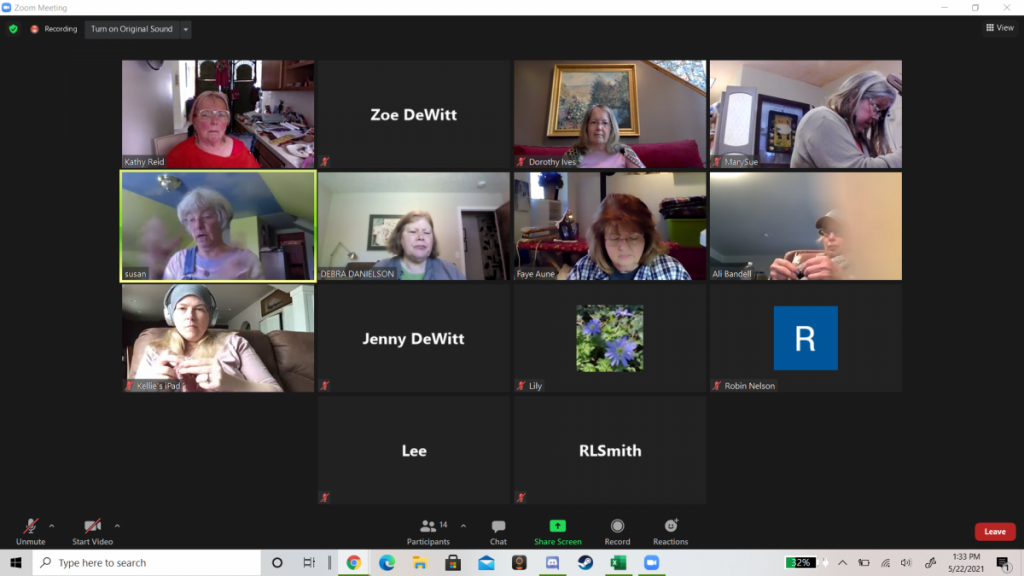

Sheep to Shawl – May 22nd

I had the wonderful opportunity on May 22nd to attend the Sheep to Shawl event hosted by the Twisted Strait Fibers group. Twisted Strait Fibers is a cooperative of fiber artists located in the Pacific Northwest area. They work to share excitement and knowledge on fiber arts, supporting one another instead of remaining distant in their fiber endeavors. Each month, TFS hosts a zoom meeting for the community to come together, and in May, this meeting was an educational event on the process of taking a piece of fiber from the animal all the way to a sellable piece. It featured Susan Kroll of Thistlehill Farm in Sequim, WA, who discussed the subjects of shearing day, skirting fleeces, washing fleeces, storing and handling fleeces, and finally dyeing.

While this event didn’t necessarily teach me anything I didn’t already know about natural dyeing or working with fleece in general, it was wonderful to come together with a group of experienced fiber artists and hear their journeys and advice. Kroll also shared photos of yarn she had naturally dyed herself, and the final colors were quite astounding and beautiful. It made me excited to work more with my family’s own sheep and fleeces, taking a fleece all the way from the animal to a spun and dyed ball of yarn myself.

Shoe Update!

The reveal! Honestly, this was not at all what I was expecting, but it was still super exciting nonetheless. It doesn’t seem like the rhododendron or the madrona bark made much of a mark, but the dried marigold made the most vivid dark spots with golden outlines. Some of the other colors I’m not even sure which material created!

Because I was hoping to get a wider variety of color during this process, I decided to do a second round of bundle dyeing with the shoes. I thought it couldn’t hurt to try again, and I still had time within the quarter to carry it out. So I went back out to forage for some more fresh materials. This time, I gathered and used a bracken fern, scotch broom flowers, a dandelion, and some pink-tipped daisies. Although I had wanted to only use foraged materials from around campus, I also decided to use some onion skins and avocado peel from the store. Both of these were highly recommended in my natural dye search so I wanted them to show up in my project in some form.

This time around, I also stuffed the shoes with scrunched-up pieces of paper so that the tongues would stay up during the dyeing process. In the above photos, it’s clear that the tongues didn’t get any dye on them, so I wanted to try and fix that this time around. I’m hopeful for more color in this second round of dyeing!

Wk 7: More Dyeing

Mordanting – Alum

For the rest of my dyeing projects, I decided I wanted to try out an easier method of mordanting. The rhubarb was great as a natural method for the process, but proved to be tricky because of the toxic aspect; it was annoying to have to ventilate my entire apartment and be wary of my roommate’s cat getting exposed. Alum (potassium aluminum sulfate), while still unsafe in large quantities, is considered to be the safest mordant to use. Not only does it act as a mordant, but it also helps to brighten the colors of dyes. Alum is considered non-toxic in small quantities, but still should not be inhaled or come into contact with skin.

Depending on the fiber used, a variety of assists may be necessary to aid the alum in the mordanting process. For animal fibers, cream of tartar can be used, and for plant fibers, soda ash can act as the assist. These assists help the fiber fully take in the alum during the process.

Mordanting with Alum

Materials

- Fiber

- Alum

- Cream of tartar or soda ash*

- Pot

- Scale or measuring spoons

- Heatproof jar

- Long-handled spoon

- pH neutral soap

1. Weight Fiber and Alum

Use 8% of the weight of the fiber in alum and 7% of the weight of the fiber in cream of tartar (amounts will vary depending on animal or plant fibers). The weight of my fiber was around 220 grams, so I used 17.6 grams of alum and 15.4 grams of cream of tartar.

2. Prewet Fiber

Just like before, always prewet fibers before dyeing or mordanting!

3. Pot of Warm Water

Fill a pot with room-temperature water, enough for the fiber to be able to move around in.

4. Measure Cream of Tartar and Alum

Put the measured cream of tartar into the jar and pour boiling water over it to dissolve. Once the cream of tartar is dissolved, add it to the pot of water and mix to combine. Repeat this step with the alum.

5. Add Fiber

Add the prewetted fiber to the pot and bring to a simmer. Cover the pot with a lid and let sit for an hour. Be sure to stir occasionally during this process to make sure the solution reaches all parts of the fiber.

6. Let Fiber Cool

After the hour is up, turn off the heat and let the fiber cool in the solution overnight.

7. Rinse and Wash

Take the fiber out of the solution and rinse with cool water. Wash the fiber with the pH-neutral soap and rinse. The fiber can be dyed in its wet state or can be dried for later use.

Dyeing – Nettle

After letting my nettle dye bath sit for three days, I discovered a film of mold over the top that smelled really awful. I was able to just skim the mold off to save the dye, but it was still disappointing to discover. After dealing with the mold, I went ahead with the dyeing process, dyeing one piece of wool I had mordanted with rhubarb and a white shirt I had mordanted with alum.

Hot Dyeing Method

Materials

- Fiber, pre-mordanted and pre-wetted

- Pot

- Stirring utensil

- Dye bath

- pH neutral soap

1. Add Fiber to Dye Bath

After adding the fiber to the dye bath, slowly raise the temperature of the bath to a simmer.

2. Simmer and Stir

Let the dye bath simmer for 1 hour with the fiber, stirring occasionally to make sure the dye is able to reach all sections of the fiber piece.

3. Let Sit Overnight

Leave the fiber in the dye bath and let everything cool after the hour is up. Let it sit overnight so the color is able to fully saturate.

4. Rinse and Wash

Remove the fiber from the dye bath after soaking and wring out excess liquid. Rinse the fiber under lukewarm water and wash with pH-neutral soap. Rinse out all soap and hang the fiber to dry somewhere away from sunlight.

Results

Honestly, these results were super disappointing. I forgot to get a before photo of the Evergreen t-shirt, but it was really just a white shirt beforehand; it seemed like the dye only slightly grayed both pieces. I guess the takeaway from this, though, is that some materials might not work for dyeing. One reason by testing the dye in advance is a good idea!

Shoe Dyeing

Finally! I was starting the process of dyeing my white Keds! I first went out to forage some fresh flowers from around the Evergreen campus. I gathered a variety of rhododendron flowers, some dandelions, a fresh marigold, and a bracken fern as well. When I came back to the apartment, I also gathered some other items as well, including foraged madrona tree bark and some dried marigolds that Caleb Poppe was very kind to gift to me.

I decided to not attempt to mordant my shoes. I wasn’t sure how to approach it since I did not wish to heat my shoes and potentially warp them at all. I also thought it would hopefully not be too much of an issue since the shoes would not have to constantly go through the wash and potentially lose color due to washing like an article of clothing might. The biggest threat would be color loss due to light exposure.

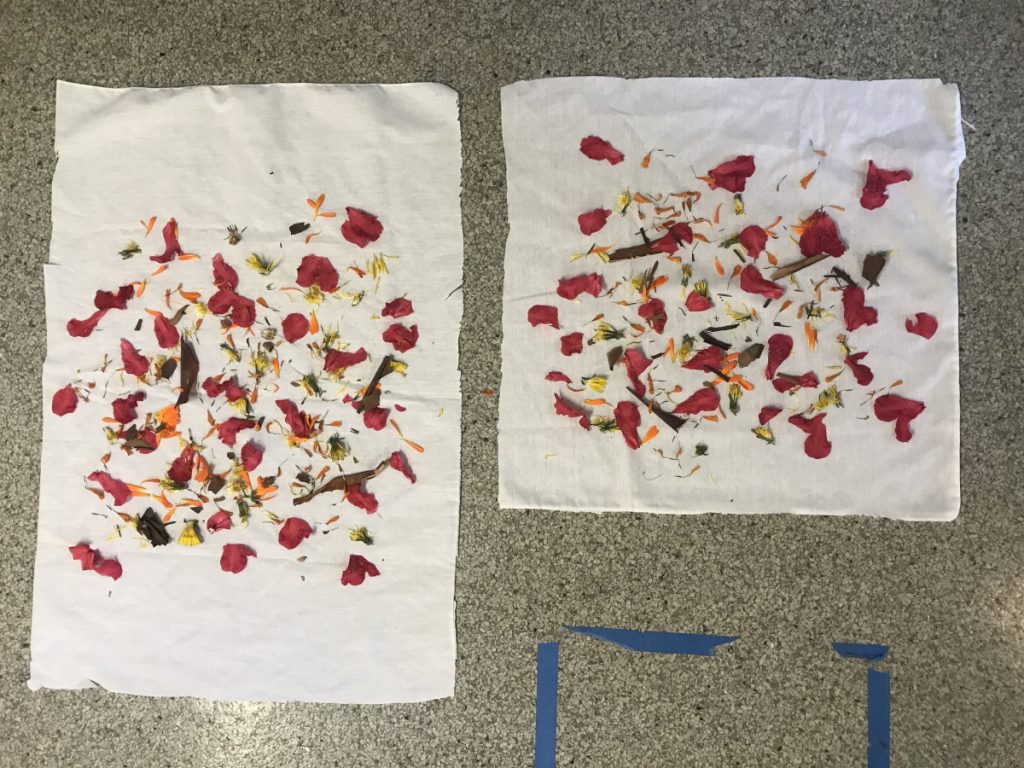

Bundle Dyeing – White Keds

Materials

- White Keds (optional)

- Fabric

- String or rubber bands

- Foraged material

- Light-colored vinegar

- Spray bottle

- Plastic bag

1. Lay Out Fabric

Make sure you have enough space to lay out the entire piece of fabric. The fabric should be pre-wetted, either right after the mordant process or after soaking.

2. Spray with Vinegar

Using the spray bottle, mist the fabric with vinegar until it is fully saturated. The acidic pH of vinegar helps with brightening colors. Some of my resources have also used vinegar as a mordant, including my high school art teacher, but other resources mention it only as a modifier because of its brightening abilities. Either way, be sure to use a light-colored vinegar, as the darker ones aren’t as effective in brightening colors.

3. Scatter Foraged Material

This is the fun part. Scatter the foraged material across the fabric. It can be random or planned out but don’t be too attached to a specific pattern, as these designs won’t usually stick. Have fun with the scattering! Break up flowers and leaves or leave them whole, leave blank spaces between materials. Just be sure to bring the material right up to the edge of the fabric so there isn’t a white border around the edge (I did not bring the material to the edges because of my focus on dyeing my shoes, not the fabric). The four specific plants that I used in my bundles were a deep pink rhododendron, madrona tree bark, dried and fresh marigold flowers, and dandelions.

4. Spray and Bundle

After the foraged material has been scattered, spray everything with more vinegar before starting the bundling process. If only dyeing fabric, there’s a variety of different ways to bundle, including a concertina fold like a paper fan or a rolling method. For me, however, I had to bundle up the fabric around my shoes, without disturbing the scattering of the plants too much. Below are the final bundled shoes, tied with string. Rubber bands would also have worked very well for holding everything together.

5. Cold Dyeing

At this point, there is a variety of different ways to finish the dyeing process for the bundles. Steaming is the fastest method, but other techniques include compost dyeing (literally sticking the bundle into a pile of compost and letting it sit for a few weeks) and solar dyeing (letting the sun’s rays help the dyeing process along). However, for my project, I chose the cold dyeing method. This method consists of tying the bundle tightly in a plastic bag (like I did) or leaving it in a sealed glass jar for at least a week. If any mold begins to appear, the bundle can be steamed for 30 minutes or put in the freezer. Then, put everything back into the bag or jar and let the process continue for as long as needed.

Wk 6: Dyeing

Dyeing Adventure – Day 1

Step 1 – Foraging

This week, I was especially excited to be able to collaborate with Grace on some dye experiments. Grace had just recently moved to a new house that had a large studio space perfect for art and natural dye work. We started off on the Evergreen campus though, and foraged for an assortment of dye materials, including Oregon grape root, blackberry leaves, nettle, and scotch broom flowers.

Step 2 – Choosing Fibers

Once we arrived at Grace’s home, Grace was very kind in letting me go through her fabric collection to find white pieces for us to dye. We ended up with an assortment of cotton, linen, and canvas materials, which we divided up between the dyes we made.

Step 3 – Making Dye Baths

I’ll be completely honest, the dyeing process was honestly scary to me. It’s the reason why I was hesitant to even mordant my fiber last week, and the reason why I have put off my dyeing until Week 6. It feels like such an intimidating task, with a lot at stake: What if the dye doesn’t come out the way I want it to? What if I completely ruin my piece of fiber? What if I waste all the plant material I harvested by not using all of the dye or by not using the dye at all?

In the end, however, dyeing is a pretty simple task, something I didn’t acknowledge until I saw Grace’s Oregon grape root dye bubbling away on her stovetop. It just takes time and patience and the right materials and knowledge. And there’s not really a way to ruin a piece of fiber; instead of being afraid of ruining a piece, approach it with a view of excitement in discovering how unique your piece will turn out.

By approaching the dyeing process head-on with support from Grace, I felt a lot more comfortable setting up dye projects on my own, which is what I did after returning home with my basket still full of nettle. Below are the steps to create a dye bath.

Making a Dye Bath

Materials

- Foraged material (leaves, flowers, roots, berries, etc.)

- Pot

- Strainer

Depending on the material used, the process of making the dye bath will vary. Notes will be made to accommodate different foraged materials.

1. Chop, Crush Foraged Material

By chopping, shredding, or crushing foraged materials for dyes, the color can easily be extracted into the water. Leaves and roots can be chopped, berries can be crushed, bark and nuts can also be chopped. Flowers are the one material that does not require chopping. Ratios of plant material to washed, scoured, and dried fiber are listed below:

1 part leaves or flowers to 1 part animal fiber or 2 parts leaves or flowers to 1 part plant fiber

3 parts roots, nuts, or bark to 1 part animal or plant fiber

1 part berries to 1 part animal or plant fiber

2. Add to Dye Pot with Water

Add the foraged material to the dye pot and pour boiling water overtop. Make sure there is enough water for the fiber to eventually move around freely.

The only exception in this part of the process is berries, which should be left to simmer for an hour after crushing. Strain out the berry residue and use the dye bath when ready.

3. Soak and Strain

Most materials need to be soaked overnight after the addition of boiling water in the dye pot. Leaves should be left to soak for 1 to 3 days, roots and bark/nuts can soak for 1 to 3 weeks, and flowers should soak for only one night. Heat can also be applied for 30 minutes to an hour to speed up the color extraction process. After the desired color has been achieved from soaking, the plant residue can be strained out and the dye bath used.

Dyes can be stored in lidded buckets or sealed glass jars for a few weeks if not used immediately. If mold appears, it can simply be skimmed off of the top before dyeing. Dyes can also be frozen in plastic containers if not used within those few weeks.

Step 4 – Celebrate with Friends!

It was very kind of Grace and Caleb to allow me to stay for their dinner party after finishing up the dyeing for the night. We had sandwiches with salami, manchego cheese, tomato, and olive oil, along with a delicious spring salad and artichoke dipped in lemon butter sauce. Grace also shared a wide variety of tea options with us from her job at Encore Chocolates and Teas; I especially enjoyed the honey ginger tea and had two mugs full of it. For dessert, Caleb brought a delicious chocolate pudding from a local restaurant which he served with strawberries and fresh whipped cream. It was a delightful meal.

I was really thankful for this evening; it was a first glimpse back into normalcy after a year of isolation and fear. Even if it was a small dinner party, it was a dinner party no less, with friends sharing stories and laughing over a table full of good food. This evening gave me hope for the future. It inspired me to look forward to in-person learning next year, with my classmates working right at my side instead of through a computer screen. It also excited me for future connections made with my classmates. This school year has been a tough one when it comes to connecting with my peers, but I think I’ve done a pretty good job of it after living through a world of quarantine during my first year of college. And if I can do a good job under these circumstances, I can’t wait to see all the connections I’ll be able to make under normal circumstances as well.

Dyeing Adventure – Day 2

The following day, I returned to Grace’s house after we let the blackberry leaves and scotch broom flowers soak overnight. I realized we had made a mistake with the blackberry leaves by not tearing them up first, so not much color had soaked into the water overnight. We fixed this by simmering the leaves separately on the stove for an hour before adding any fiber.

By adding the fiber to the mix of plant material, Grace and I were experimenting with the all-in-one dyeing method. This is the combination of the fiber and foraged material together in the dye pot, instead of the creation of a separate dye bath that the material is strained out of, which is known as the hot dyeing method. I left Grace’s house before I could see the end results of the all-in-one method, as the fiber needed to soak overnight in the pot. I am so appreciative of Grace for sharing her home with me and for working with me in my first dye experiments.

Wk 5: Mordanting

Mordants

In order for dyes to fully stick to fiber, they require a fixative, known to dyers as a mordant. Mordants help the colors from dyes chemically bond to fibers. The word, itself, comes from the word mordere, meaning “to bite” in the Latin language. This relates to the function of a mordant: it assists the color in “biting” into the fiber so that it can resist changes from light exposure, washing, or rubbing.

The process of mordanting can occur at any point during the dyeing process, but it is important to know when and also which mordant will be best depending on the type of fiber being used. It is also important to understand that mordants can influence the final color of the dyed piece. The below chart from the book, Botanical Inks by Babs Behan, illustrates the differences seen when using different types of mordants on different types of fibers.

For my project, I have chosen to use oxalic acid, a natural plant-based mordant that can be extracted from rhubarb leaf. I chose rhubarb leaf because of the natural and renewable qualities that it holds, unlike synthetically made mineral-based mordants. Rhubarb leaf is also safer to dispose of and was already available to me on my family farm, unlike other commonly used mordants. The drawback of rhubarb leaf and plant-based mordants in general, however, is that they very often leave a tint of color if used before dyeing. It won’t be an issue if deep colors are what the dyer desires, but light colors may be harder to achieve when using these mordants.

Alternative plant-based mordants that can be used when dyeing fibers include tannic acids, which can be found in oak galls, oak bark, acorns, chestnuts, and other tree barks and nuts. These work best with plant fibers, while oxalic acid (which can also be found in borage and certain seaweeds) is best when working with animal fibers. Mineral-based mordants can also be used, the most common ones being iron and a combination of alum (potassium aluminum sulfate) and an assist (either cream of tartar or soda ash depending on fiber-type). Both of these metals are safe to use in small quantities and if used properly, should be fully absorbed by the fiber so that none is left within the water and it is safe for disposal. Either way, however, is it important to use safety when working with and disposing of any mordant, whether it be plant or mineral-based.

Safety is an important consideration for my project because even though I am working with a plant-based mordant, oxalic acid can be highly toxic. As the acid is heated, it luckily gets broken down and becomes non-toxic and safe for use as a mordant, but the heating process of the raw leaves is still of concern to me. The fumes from the heating process are toxic if breathed in, and since I am working out of my tiny apartment kitchen, I will need to figure out how to ventilate the space while carrying out this part of the project. I am planning on leaving windows open, having the kitchen fan on, and of course, wearing a mask and gloves if interacting directly with the leaves. However, if I figure out a way to be able to work outside when extracting my mordant, I will surely do that instead!

New Materials!

To expand my natural dye materials, I revisited my local Goodwill and lucked out on some good finds. The best find of the day was an old scale, something I was in search of but didn’t get my hopes up to find. This scale will be a perfect aid in the mordanting process, as I will be able to take proper measurements of fiber and rhubarb leaf values to get the mordant amounts correct. I also found a large jar for storing the mordant mixture. I am not sure if it will be large enough for all of the mixture but I also may carry out the mordant process in multiple stages instead of all at once, so I am hoping the jar is perfect for a single batch. Finally, I bought a fun pair of gardening gloves for future foraging adventures, especially ones that involve the collection of nettle.

The Mordanting Process – Rhubarb Leaf

Materials

- Fiber (washed, scoured, and dry)

- Rhubarb leaves

- Scale

- 2 large pots

- Long-handled spoon

- pH neutral soap

Process

1. Weighing the Fiber

The weight of the fiber you are mordanting is important in determining the amount of rhubarb leaf to use in the mordant solution. As a general rule, use 200% the weight of the fiber (WOF) in rhubarb leaf when making a mordant. For example, I had around 42 grams of washed and scoured wool, so I used 84 grams of rhubarb leaf in my mordant solution.

2. Allow Fiber to Soak

Soak the fiber in a large pot for at least an hour, although 8 to 12 hours is ideal.

3. Wash and Cut Rhubarb Leaves

Wash and cut (or shred) the leaves into tiny pieces. Place them in a separate pot so that they can be fully submerged in water.

4. Boil Leaves in Pot

Pour enough boiling water over the leaves to cover them. Then bring the water to a simmer and cover the pot with a lid. Simmer for 1 hour.

5. Strain Out Plant Material

After the hour is over, let the solution cool off before straining or scooping out the plant material. Once you have the final mordant solution, it can either be stored in jars for later use or transferred into a pot that is large enough to hold the fiber you are mordanting. The fiber should be able to move around freely within the solution. More warm water can be added to the pot if there is not enough space.

6. Add Fiber to Mordant Solution

Once the fiber has been added to the mordant solution, bring the pot to a simmer for another hour with lid cover. The fiber should be stirred occasionally with the long-handled spoon. This releases any air bubbles trapped in the fiber. It also moves the fiber around so that the mordant can reach all parts of it, as some of the wool may have been at the surface or touching the sides of the pot.

7. Wring Out Excess Liquid

After the hour is over, let everything cool before moving the fiber out of the solution. Wring out any excess liquid within the fiber.

8. Rinse And Wash Fiber

Rinse and wash the fiber with cool water and pH neutral soap. Rinse again to remove all soap.

9. Dry the Fiber

While the fiber can be used in its wet state for dyeing, I chose to dry mine for later use. Make sure to air dry the fiber somewhere warm and out of direct sunlight.

It was interesting to see how the rhubarb mordant interacted with the wool, dulling the color from a lovely snow-white to a grayish brown. This showed how using a rhubarb mordant might not be desirable for some dyers depending on the color they are trying to achieve.

Wk 4: Foraging

Foraging Prep – What Excites Me?

The foraging aspect of my project was insanely exciting to me, but also a little daunting. I have never done much foraging in the past, and while I have been anxious to get into it ever since arriving on the Evergreen campus, I haven’t quite known where to start. Writing up a list and doing research on local forage for natural dyes was a great way for me to get into it. I poured over book after book, discovering more and more plants and more and more projects to use them in. The following is the list of natural dye plants that I compiled from this research, most of which I can find locally right on the Evergreen campus.

Natural Dyes that Excite Me:

- flowers (daffodils, dandelions, cherry blossoms, etc.)

- onion skins*

- avocadoes*

- tea*

- bracken fern

- rhubarb (used as a mordant as well)*

- blackberries (salmonberries too?)

- sorrel

- tansy

- nettle

- alder

- queen anne’s lace

- ivy

- mahonia

- horsetail

*starred items are dyes that will not be foraged and will instead be obtained from local farmers’ markets, co-ops, and stores as a last resort

Foraging Adventure

The Evergreen woods was the perfect place to begin my foraging journey. Not only was this a place that I had formed a deep connection with and had grown to know and love, but many of these natural dyes were already heavily available within these woods. So on a sunny afternoon, I set out with my basket and pocket knife for my first foraging adventure.

This was my final basket after a long day of foraging, minus the dandelions and daffodils that I had foraged separately at a later time. I was really excited with all of my finds and had taken some of my natural dye books with me to do research on the trails when encountering new plants I was unsure of. This entire process felt like I was creating an entirely new relationship with the woods; I wanted to be cautious of how much I was taking and how I was treating each plant when harvesting. It’s very easy to get excited when running across a plant for foraging and to forget that this plant is a living being as well. Treating the woods with respect is an important piece to remember on any foraging adventure.

Produces a light to mustard yellow

Produces a rusty orange

Produces a coffee stain brown

Can produce a variety of browns, oranges, and greens

Produces a lovely yellow

Mordant Harvest

Later in the week on a visit back home, I was also lucky to be able to harvest some rhubarb leaves from my family’s farm. Rhubarb leaves, while toxic when consumed, are used in dyeing as a natural mordant, a fixative that helps dyes better connect to the fiber (more mordant research will be shared next week!). I was thankful that rhubarb was growing on my family’s farm and my parents allowed me to harvest it, as I would’ve a hard time finding the leaves anywhere else because of their toxicity.

Instagram Inspiration

As phones often do, my phone seemed to pick up on the fact that I was starting a project surrounding the use of natural dyes, and it surprised me one morning with an ad on Instagram for naturally dyed Vans products. Upon doing further research on the subject, I found the story of Karla Almendra, a textile artist from Mexico. She had partnered with Vans to create a number of naturally dyed Vans products, with the sole purpose of keeping the natural art of textile dyeing alive. She emphasized the unique qualities of every piece created, how she never knows how the piece will turn out until she’s unfolding it after the dyeing process. The story was quite beautiful to me, but it was also quite inspiring.

The key featured item that Almendra created was a pair of naturally dyed white Vans shoes. She dyed them through the use of dried flower petals which she laid out on a piece of cloth and then wrapped around the shoes, tying it all together with string. After carrying out the dyeing process, she unwrapped the shoes to reveal a beautiful array of colors, as seen above.

This project completely inspired me. I had wanted to find some special bigger project for myself to attempt during the quarter, and this felt like the perfect one to take on. So almost instantly, I went out in search of a pair of cheap, white shoes. I found these Keds at a local Ross, which was a lot cheaper than a new pair of Vans would’ve been for me. I am very excited to figure out how to dye them!

But that’s one of my problems. I’m not entirely sure how to dye these shoes. The Vans website doesn’t share Almendra’s recipe for dyeing, and Almendra, herself, does not have a website or place where she would share any tips or wisdom. This means I’ll have to figure out how to dye them on my own.

I have decided to try a version of bundle dyeing for the shoes. Developed by a modern-day textile artist from Australia, India Flint, this process uses dyes from fresh flowers and plants to infuse colors into whatever material is being dyed. It involves the scattering of flower petals and other plant material across a fiber piece and then bundling it up in a specific pattern or roll. It is the closest dyeing technique I can find to what Almendra did with the shoes; it just adds the aspect of bundling the fiber up around a pair of shoes.

Because of risks of damaging the shoes through the process of hot bundle dyeing, I will be attempting the cold dyeing method, where the shoes will be tied up in a plastic bag and left to sit for at least a week, if not longer. I am hoping that my research has paid off and I will have a nicely dyed pair of shoes by the end of this quarter.

Wk 3: Wool Prep

Why Wool?

Wool has been a part of society for millennia. Between its warmth, durability, and natural properties, it is no wonder that this animal fiber is the most common one in the world. After forming a relationship with sheep around 8 thousand years ago, farmers all around the planet are today raising one billion sheep collectively, the majority of which are in China. In the United States, sheep farms are primarily focused on meat production, with little thought given to the fiber of the animal. It is the small-scale sheep farms that focus on selling the wool, showing up with their products to local farmers’ markets and other online marketplaces. When sourcing wool and yarn for a project, it is important to support these local small farmers that put their love and care into these fiber products.

Wool is a great fiber for beginner dyers. Animal fibers like wool, silk, and alpaca are more successful at taking in and holding onto dyes when compared to plant fibers, and can often be dyed without a mordant. However, animal fibers can also be very delicate and need to be processed more gently than plant fibers. It is recommended to use cold or low-temperature dyeing techniques in order to maintain the quality of the fibers. With wool, specifically, it can shrink and felt if exposed to extremely hot temperatures, so allowing for temperature changes to occur naturally instead of shocking the fibers is an important step in the process.

Washing the Wool

After the sheep shearing over spring break, I sorted through the leftover scraps of wool from the fleeces and chose a good collection of white, gray, and brown colors that I could start off experimenting with dyeing. I thought that a test of dyeing wool before jumping into full pieces would be a good way to ease into the world of natural dyeing. Plus, I had already worked with wool in the past so it felt like a safe place for me to start.

The first step in any dyeing project is to wash and scour whatever fiber you will be working with. That way, no dirt, dust, or grease that could potentially disrupt the color and quality results of the dye remain hidden within the fibers. To wash fibers, they can be put straight through the washing machine or can be hand washed if they are too delicate for a machine washing (like mine). Next, to scour fibers, put them into a non-reactive pot with enough water for the fibers to move around freely. Add an ecological soap, around the same amount you would use for laundry, and bring the water to a gentle simmer (if using plant fibers, bring the water to a boil). Let the fibers simmer for an hour with occasional stirring, before turning off the heat to cool. Dump out the dirty water and replace with clean water to rinse the fibers. This scouring process may need to be repeated a few times until the water runs clear, meaning all dirt and debris has been washed away. Fibers can be used right away in their wet state, or they can be hang dried and stored in sealed bags or boxes until use.

This process took a lot more time and patience than I had expected. The amount of wool I had to scour was a lot more than could fit into my one pot, so I had to repeat the process over multiple nights with multiple batches of wool. My kitchen felt too cramped to work in, and I definitely felt the constraints of living in a shared college apartment compared to having the outdoor workspace back on my farm at home. It was frustrating at times, especially when figuring out where to dry the wool with a curious kitten wanting to attack it, but I figured it out and got it all done in the end.

Thrift Store Find

As part of my project, I wanted to find different materials to experiment with dyeing, so thrift store exploring has been a highlight for me. I found this beautiful lace curtain at the local Olympia Goodwill and am just ecstatic to get it dyed. I have not decided on a color yet, but a nice brown-ish orange color created by using onion skins as a dye might give it a nice “aged” look which I am considering. The one downside to this piece is that it does not have a tag displaying the fibers it is made out of, but just from feel, it seems like a synthetic material to me. I will have to do some extra research to learn about dyeing synthetic fibers, and will most definitely be using a mordant in the process.

Wks 1 + 2: Getting Started

Introduction

I chose to create a project surrounding natural dyeing as a fiber art because of the sheep back on my family’s farm in Kingston, WA. I had worked with their wool in the past through making a vegan sheep fleece rug, which was a highly time-consuming but fun project for me. That sheep fleece rug now lies on the floor of my bedroom and is the inspiration for this spring quarter project.

While I am not entirely sure if I will be working with a lot of wool this quarter or if I will mostly be focusing on other, more available fibers, I am excited to learn and start my journey with natural dyes. I am excited to experiment and forage and make mistakes but also create beautiful art through such an interesting area of fiber arts. I hope to carry this passion with me for a long time.

What is a Natural Dye?

A natural dye is a dye or colorant that is created through the use of naturally occurring materials. Most natural dyes today are derived from plant material, such as leaves, flowers, roots, bark, and berries, but the use of certain insects and minerals has also been traced back over thousands of years. For the purpose of this project, I will be sticking with foraged plant material for my dyes, but some of my research will encompass the use of other natural dyes as well.

Resources

My mother had ordered a bunch of natural colorant books that she let me borrow and use for my project. The majority of them contain very similar information on dyeing techniques, materials, and natural colors available in different areas. The Handbook of Natural Colorants edited by Thomas Bechtold and Rita Mussak is a valuable find because of its information on the history of natural dyes and specific antique colors. Finally, I was very fortunate to get in touch with multiple natural dye experts, including my old high school art teacher, Kathy Griffey, who gave me Spinning and Dyeing Yarn by Ashley Martineau and also A Dyer’s Garden by Rita Buchanan.

Materials

Working out of Harvesting Color by Rebecca Burgess, I compiled a list of tools necessary to create a beginner’s dyeing kit:

Beginner’s Dyeing Kit:

- Scale*

- Measuring spoons*

- Alum*

- Litmus paper for pH testing*

- Pots (assortment of copper, stainless steel)

- Bowls

- Stirring utensils (assortment)

- Hot plate/camping stove for outdoor use*

- Gathering basket

- Clippers/scissors

As of the end of Week 2, I had only compiled 3 of these required elements of my dyeing kit. I had discovered that being a money-conscious college student living in an on-campus college apartment would prove to be one of my bigger setbacks throughout this project, starting with the fact that I just don’t have the money to go around spending on a bunch of dyeing equipment. Because of this, the starred items within the above list are what I have considered unnecessary for my current project. I made these choices based off of my research on different dyeing processes I hope to try throughout the quarter, and also on the fact that I am really excited to just jump in and experiment without the need of exact measurements or known pH numbers. The one item I am most disappointed to have to deem unnecessary would be the outdoor cooking stove. Working within the constraints of my tiny apartment kitchen will be a challenge for me; I would much prefer to be able to work out in the open without having to worry as much about making a mess.

Spring Break Prep!

Barnswallow Meadows’ Sheep Shearing – March 19th