Content Warning: brief mention of sexual assault

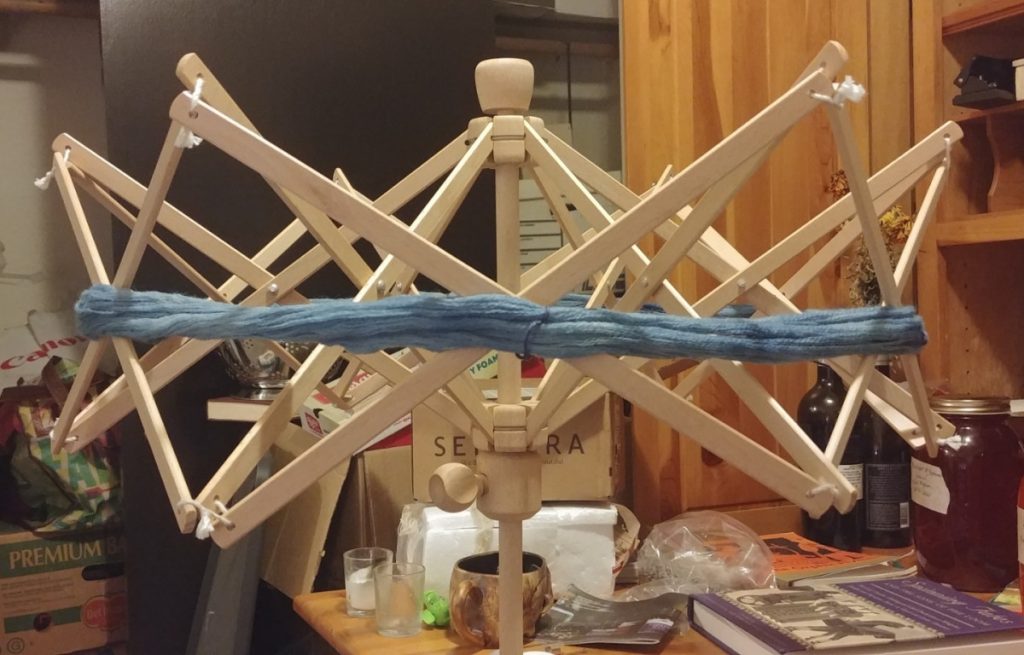

The last eight and a half months have lead to this moment: the moment I finished my project. I finished the last bit of sewing on Monday and immediately fulled it. Fulling a fabric after you’ve finished weaving it is quite important. At the very least, a handwoven textile should be finished by soaking it in hot soapy water; if you want the textile to be a bit sturdier, you full it. The simplest way to full (and the only way I have experience with) is to do the steps for creating felt without going so far as to actually create felt: you soak the textile in hot soapy water and agitate the heck out of it.

I made my life a bit harder at this step by not buying a bucket or large container in which I could do the fulling. I also didn’t want to fill up my bath tub because that would use more water than I needed. Luckily, my fiance and I had just bought the day before a new rubbish bin for the kitchen that we hadn’t used yet. So, I placed it in the bathtub and fulled my himation inside. It worked like a charm! And it was definitely a workout; I forget the wool can absorb nearly half its weight in water, so fulling became an arm workout. Once I finished fulling, I hung it up to dry above my bathtub using hangers to hold it up.

The next day the himation was fully dry and there was only one step left: to cut off the little tails of weft I left in while leaving. Now that the himation was fulled and definitely not going to fall apart anytime soon, it was safe to trim those tails. And then…I was finished. Three quarters of fiber work and this is the result:

I’m not great at admitting when I’ve done something cool or impressive, but even I have to admit: this is impressive. I also felt the need to model the himation to demonstrate how it would have been worn (and perhaps to show off, I will not lie).

All that was left after this was to present to the Terroir/Merroir program, write my Academic Statement and self-evaluation, and catch up on all of the weekly summaries I forgot to keep doing. Writing this post is one of the last things I’ll do as an undergraduate student.

This school year has been wild. I’ve spent a good time alone because of the pandemic. I made a garment by hand completely from scratch (well, nearly as I bought the warp yarn). Many tears were shed: from frustration, anxiety, pain. There was a good amount of pain. I bled several times from the combs, scalded myself a couple of times while dyeing, and used my body to the breaking point while spinning and weaving. I have a completely different perspective on clothing now. If I was paid minimum wage for every hour I spent on my himation, the dollar amount would be $3,264.31. The concept of Slow Fashion has never been clearer to me and I think I will visibly flinch when I walk by stores such as H&M and Forever 21, with their $5 shirts and $30 dresses. That cost is asinine and speaks volumes about the lives of the people who actually made those clothes. The story is there for anyone who cares enough to listen.

Something I wish I had done this quarter was read. I bought a great book for the quarter titled Spinning Fates and the Song of the Loom: The Use of Textiles, Clothing, and Cloth Production as Metaphor, Symbol, and Narrative Device in Greek and Latin Literature. I had wanted to incorporate this book into my learning after reading, “Women’s Work: Spinning and Weaving in the Greek Home”. I was struck by an idea the author brings up:

“…or is the production of textiles merely a literary topos, which serves mainly to remind us that Greek men conceived of women as spiders who trapped unlucky men in their webs? …The study of textiles in Classical Greece is a complex tangling of two realities: physical reality, where flesh and blood women transform wool and flax into tunics and blankets, and psychic reality, where metaphorical women spin out the lives of men, and the Fates (always women) cut the threads to kill men, and where Circe traps helpless men in her complicated webs.”

Part of why spinning and weaving were assigned to women in ancient Greece was to “keep an eye on them” – to control them. Women were seen as liminal and therefore dangerous. In essence, a bunch of patriarchal garbage. But anyone who takes a deep dive into Greek mythology (and I have, I’ve been obsessed since I was a child) will notice that spinning and weaving are used in clever and dangerous ways by various feminine entities. There is, of course, Arachne, whose weaving skills were so renowned that Athena herself challenged Arachne to a test of skill; Arachne’s dangerous defiance of the gods transformed her into a spider, so she may weave forevermore. Medea kills the new wife of Jason, who Jason set aside Medea for, with something she weaved. Herakles dies from a poisonous garment his wife, Deianara, gave him; she thought the poison was a love potion that would keep Herakles from straying. Even Penelope, the patient wife of Odysseus and seen as the perfect example of how a woman should be, kept her suitors away by undoing the shroud she was weaving for her father-in-law; Penelope declared she would choose a suitor once she was done with the shroud, but would undo most of her day’s work to deceive the suitors. And the feared Moirae, the Fates, who all – human and god – were at the mercy of, were depicted with a spindle. Clotho spun a person’s destiny, Lachesis measured the length, and Atropos cut the thread.

This motif seems to exist outside of ancient Greek mythology. I didn’t have much time to explore this, but off the top of my head I know that Valkyries, the battle maidens of Odin who carried off fallen warriors to Valhalla, have an association with weaving. Though, their example is gruesome: they weave with the entrails of dead men and their loom weights are severed heads. Spinning and weaving are not safe activities. There is power to be found in these crafts, in so-called “women’s” work.

Weaving is an act of defiance, which I feel is best illustrated by the ancient Greek story of Philomena. Philomena was the sister of Procne, who was married to Tereus, king of Thrace. Tereus lusted after Philomena and, not caring that she was his wife’s sister and taking full advantage of the power that he had and she didn’t, raped her. Tereus goes even further and cuts out Philomena’s tongue so she can’t tell anyone what happened. So what does Philomena do? She weaves her story, her trauma, and pain into a tapestry. She shows this to her sister, and Procne avenges her by killing her own son with Tereus and tricking him into eating their son .

Tereus tried to take away Philomena’s voice and power. But Philomena used that dangerous skill of weaving in order to reclaim her power. She remained defiant of the society that oppressed her and condoned her trauma. The consequences to Tereus are devastating. In a society that would not allow women a voice, the women of ancient Greece, at least in the myths, used the skills that they had to their advantage. They told their story through fiber arts.

And so is the case for me in my himation. Yes, it looks like a long blue, red, and yellow piece of fabric that will keep me warm when the winter months come upon us again, but it’s so much more than that. My himation tells the story of my final year at Evergreen; it is the culmination of 15 years of working towards my BA degree. Fibers of loneliness, isolation, and fear spun along with wool speak of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is soaked in the tears shed due to the physical and mental anguish I experienced while doing this work. It is dyed using knowledge I sought out to connect with my ancestors, so they, too, are in my himation. Intertwined among the warp and weft are all of my thoughts, feelings, and memories that came up while creating it. Finishing it is my expression of defiance – defiance in the face of those who did not believe in me and didn’t support me. My himation is the story of myself.