Native plant ID:

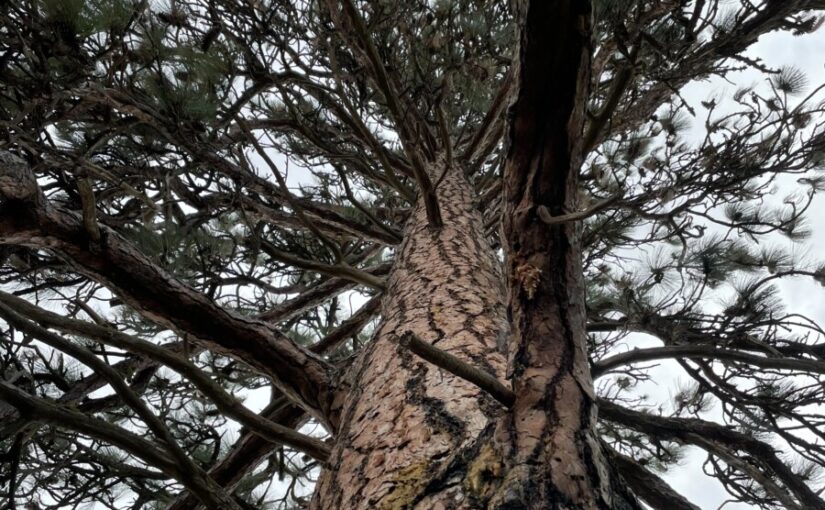

Ponderosa Pine, Pinus ponderosa

The Ponderosa Pine is a towering evergreen that can reach up to 200 feet in height. This beautiful tree is a home to many, offering habitat to native insects and birds. Its long needles are often in bunches of three and its bark resembles puzzle pieces.

Ponderosa Pines are wind pollinated and prefer sun to part shade. The tree tolerates poor soils well and is drought tolerant once established. Ponderosas are important for native wildlife and provide “forage, cover, nesting sites, and nesting materials” (1).

The habitat for these pines is typically “dry, open areas, open forests, and mountain slopes” from British Columbia to Mexico and east to the Dakotas.

At Steep Creek Ranch, Pinus ponderosa (pictured above) can be found everywhere on the property and in the surrounding landscape.

Practicum and Learnings Summary:

Monday:

On Monday, I started the day off with our regular Monday chore of turning the compost pile. After this, I spent time weeding the staff garden and planting the new starts (Japanese and Italian eggplants, Persian cucumbers, Malabar spinach, scarlet runner pole beans, an heirloom tomato, more strawberries, rhubarb, a black currant, culinary sage, oregano, thyme, and rosemary).

Tuesday:

On Tuesday, I checked the soil moisture meters, many of which had higher numbers, but some lower due to a recent rain. Some of the Syrah showed signs of tip burn and the soils there felt much drier than the lower blocks of the Syncline estate. After checking the soil moisture meters I spent time cleaning up any debris in the staff garden from previous weeding.

Wednesday:

On Wednesday, I had a short meeting with our field supervisor Dr. Michael Beug about our progress, achievements, and overall satisfaction at the end of the quarter.

Sunday:

On Sunday, my peer and I spent the fist half of the day with our field supervisor on Mt. Adams and the surrounding area. We ventured out into the forest with the goal of finding some edible mushrooms (or any mushrooms). At our first stop, Dr. Beug showed us an incredible example of Indigenous agriculture: a cranberry bog nestled beneath the beautiful mountain. The biodiversity was stunning and we were in awe of the beauty of this very special place. After appreciating the beautiful bog, we moved on to the disappearing lake close by to hunt for morels but sadly did not find any mushrooms of interest other than the fungal plant pathogen: Taphrina alni (Alder tongues). After this we explored the ice caves an surrounding area observing the gorgeous ice formations and hoping to find morels around the caves. Then, heading lower in elevation towards Troutlake, we stopped and found some tulip cup mushrooms and some spring king boletes. For our final stop, we took a short hike at troutlake, where there was a beautiful trail with a lovely view of the mountain as well as sleeping beauty mountains.

Link to instagram video of our day posted by Dr. Michael Beug

Seminar: Growing a Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back to Life by David Montgomery

In chapter eleven, “Farming Carbon,” David Montgomery addressed carbon sequestration, the power of mulch, conventional environmental issues, and no-till farming. Montgomery explores how no-till practices combined with cover cropping can sequester carbon in soils while conventional and tillage methods actually release carbon into the atmosphere due to the acceleration of decomposition caused by tillage. The argument that no-till is less environmentally impactful also includes the fact that less equipment passes are required to farm a field while at the same time soil carbon is not being released. Heavy machinery also burning more fossil fuels during tillage because of the intense drag caused by breaking the soil with plows. “…since the dawn of agriculture, most cultivated soils have lost between a third and two-thirds of their original soil carbon” (p.209-210). Montgomery mentions that carbon sequestration is possible short term solution that can be impleemented immediately to “buy us time” to develop truly green energy alternatives to fossil fuels.

In chapter twelve “Closing the Loop,” David Montgomery discussed closed loop systems with a focus on humanure. This chapter addresses historical uses of humanure and the fact that the United States losses too much of our soil nutrients through waste disposal, both human waste and food waste, and the exporting of nutrients off the farm without replacing them with organic matter. Montgomery talks about the successive return of nutrients in natural cycles, such as weeds drawing nutrients from the subsoil and returning them in plant available forms to the topsoil upon decay. It is in this way that he views humanure as critical for returning nutrients to our fields. An example of a more modern way human wastes can be reapplied to our soils comes from Tacoma, Washington’s sewage treatment plant. The product TAGRO, is a microbially digested fertilizer made from a mix of biosolids, sawdust, and sand, and has become popular in the city.

In chapter thirteen, “The Fifth Revolution,” David Montgomery concludes his learnings of soil building and regenerative farming practices, reflecting on the ways in which conventional agriculture does mostly harm rather than good. Montgomery notes that although soil building practices, enhancing fertility, and causing less environmental damage are relatively simple practices that are easy to adopt, politics must change to allow this and strategies must be tailored to each place. Bolstering agricultural and community resilience in the face of climate change is a daunting task, but one that can be accomplished if farmers stray from the sways of agribusiness corporations. Ideally, conventional farmers could realize that lower input practices will save their land and their wallets. This is how we need to move towards a post-oil world.

Bibliography:

- Currin, Kristin, and Andrew Merritt. Pacific Northwest Native Plant Primer: 225 Plants for an Earth-Friendly Garden. Timber Press, 2023.

- Montgomery, David R. Growing a Revolution: Bringing Our Soil Back to Life. W. W. Norton & Company, 2018, Ch. 11, 12, 13.