This year, I had the joy of celebrating the Lunar New Year with my friends and roommates. On the 22nd, we all piled in to our small living room and kitchen area to share in a meal and watch a movie. It was a relaxing evening, despite how busy the kitchen felt while cooking.

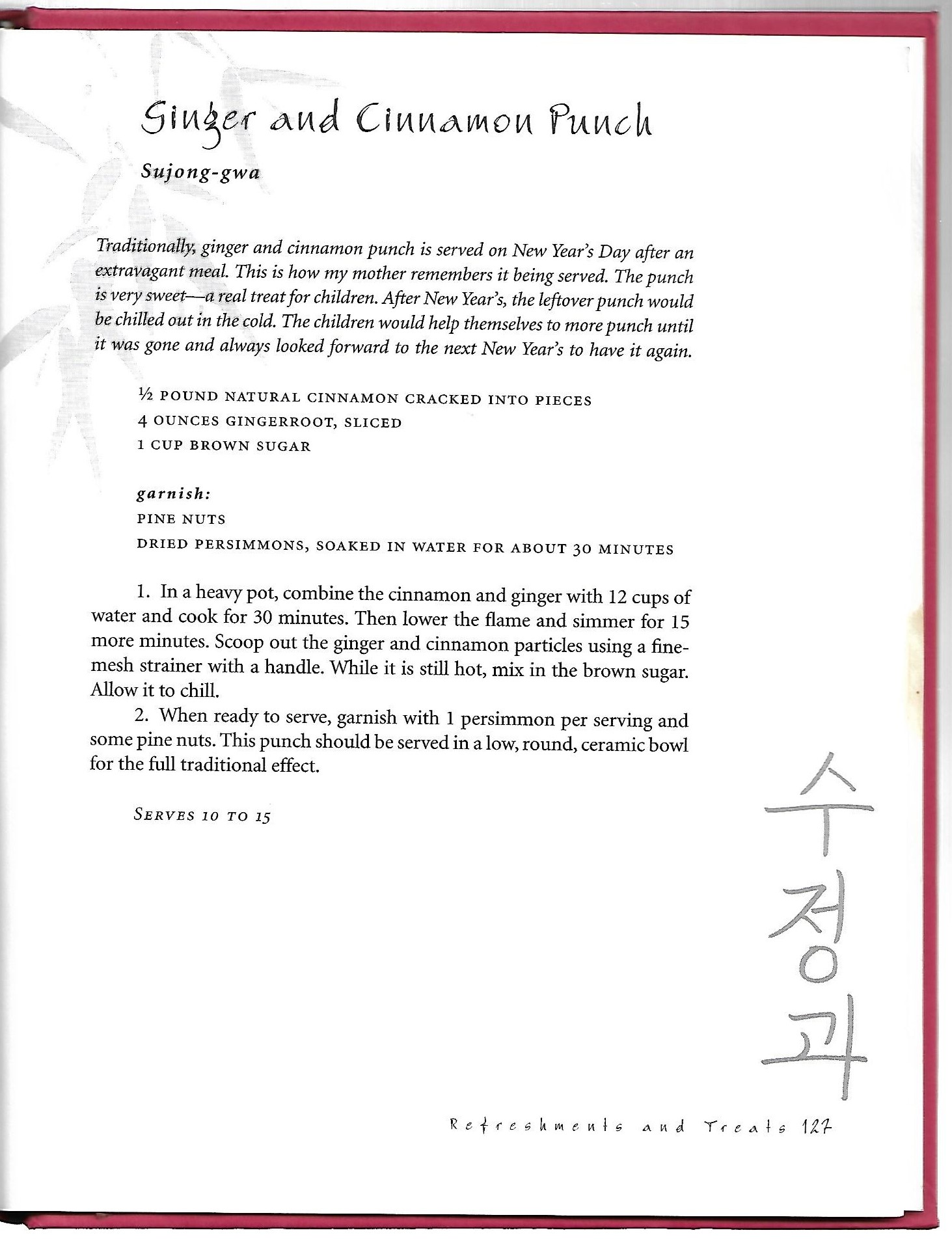

The ginger & cinnamon punch (수정과) was the first recipe I started on, cooking it the day before Lunar New Year. It felt fitting to cook it then, not only in the name of saving myself some time, but because the Korean Lunar New Year celebration Seollal (설날) last three days, this year beginning on January 21st, and as Jenny Kwak details the punch is meant to be served on New Year’s Day. While Kwak may have been referring to January 1st New Year’s Day, I decided to use it for Lunar New Year.

Cooking the punch was an almost meditative process as I moved around the kitchen on my own. I decided to forgo music and go through the motions in silence, taking notes of the process as thoughts occurred to me.

Prepping the ginger was fairly simple, all that needed to be done was washing and slicing the root before dumping them into a pot filled with 12 cups of water. I really enjoyed the easy preparation; fresh ginger is one of my favorite scents, reminding me of when Dad would make tea for me when I was sick. It was the cinnamon that was a touch more of a challenge. As shown above, Kwak notes that the cinnamon needs to be cracked into pieces. So , there I stood in the kitchen, looking around and trying to think up a way to crack eight ounces of cinnamon sticks. As I often do in my cooking, I turned to my memories of Mom in the kitchen and asked, what did she do to bust up hard ingredients? And suddenly I remembered; I would need a plastic bag, a cloth towel, and something heavy I could wield like a hammer. Dumping the cinnamon sticks into a zip lock bag, I wrapped them in a kitchen towel and laid it on the counter. Next, I turned to the cupboards, rifling through for something heavy enough to crush the cinnamon sticks. Picking a small metal pot that I rarely use, I felt the weight in my hand, noticed how the heavy bottom caused my wrist to bend, and decided this was the pot to get the job done. Pot in hand, I turned back to the counter and gave the cinnamon a tentative whack. It was this rather comical scene that my roommate Anahí walked in on. She was just coming into the kitchen to get a glass of water, but instead saw her roommate assaulting a bag of cinnamon sticks.

Being the great friend that they are, they were quick to offer to be my photographer for this step of the cooking process. With a lot of laughs, and a lot of hits, I successfully crushed the cinnamon into pieces. Once that was done, I emptied the bag into the pot of water to join the ginger.

The next step was to cook the contents of the pot on the stove for 30 minutes, a task that took a little longer than the recipe called for. As I watched the pot take forever to get hot (I know, I know, a watched pot never boils) I lamented our lack of a gas stove, wishing I was back at my parents house for a moment. Eventually the water began to simmer and boil and the whole apartment smelled of cinnamon, a tang of ginger lingering just behind.

As the ingredients boiled, the water began to take on the rich brown color of the cinnamon, even the ginger began to darken in color. Near the end of the cooking period, the smell became even more intense, tickling the back of my nose. After it was done cooking, I strained the punch into a large metal bowl to cool down. While it was still hot, I mixed in the brown sugar, the smell taking on a light sweetness to soften the spice of the cinnamon.

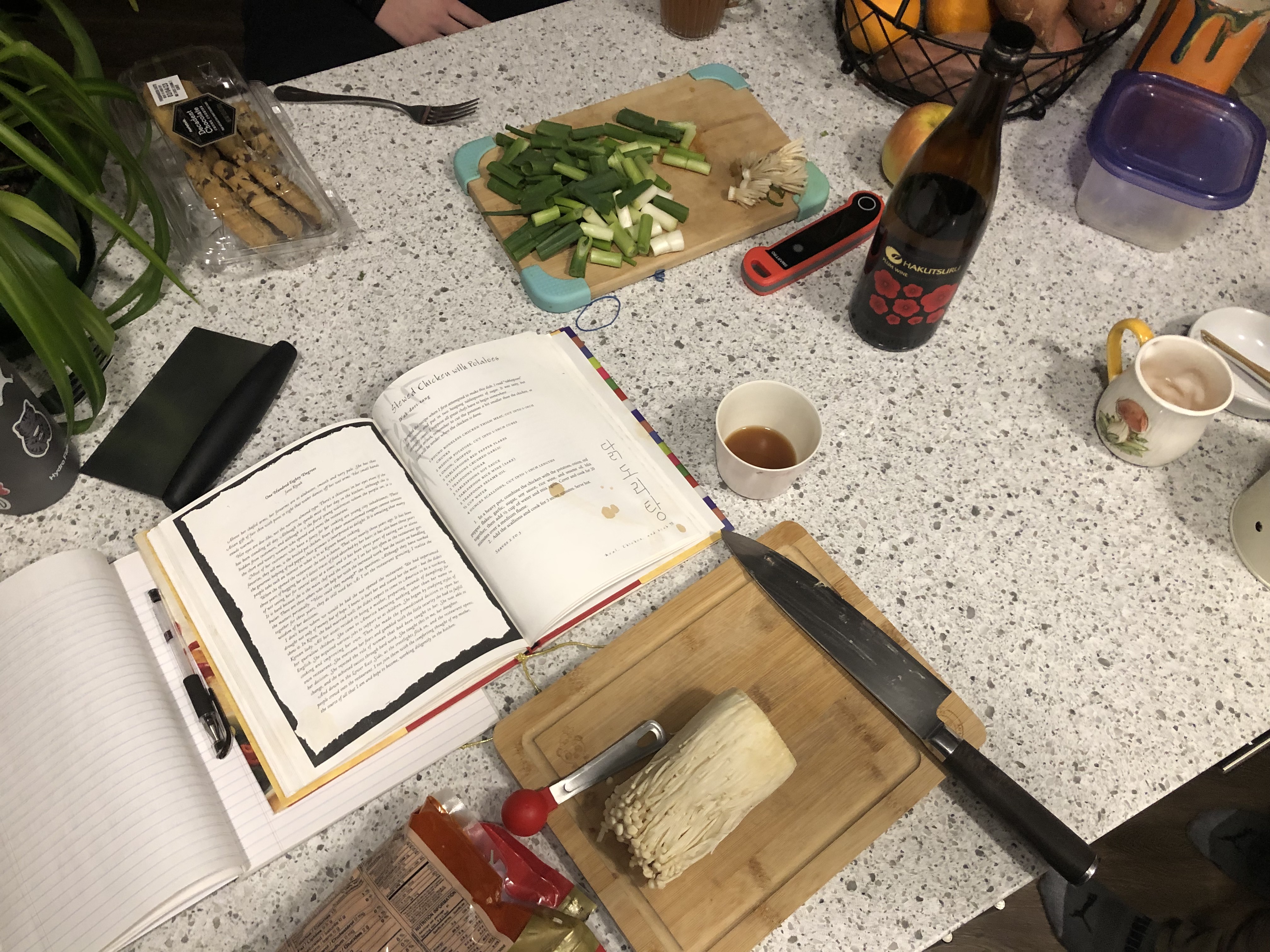

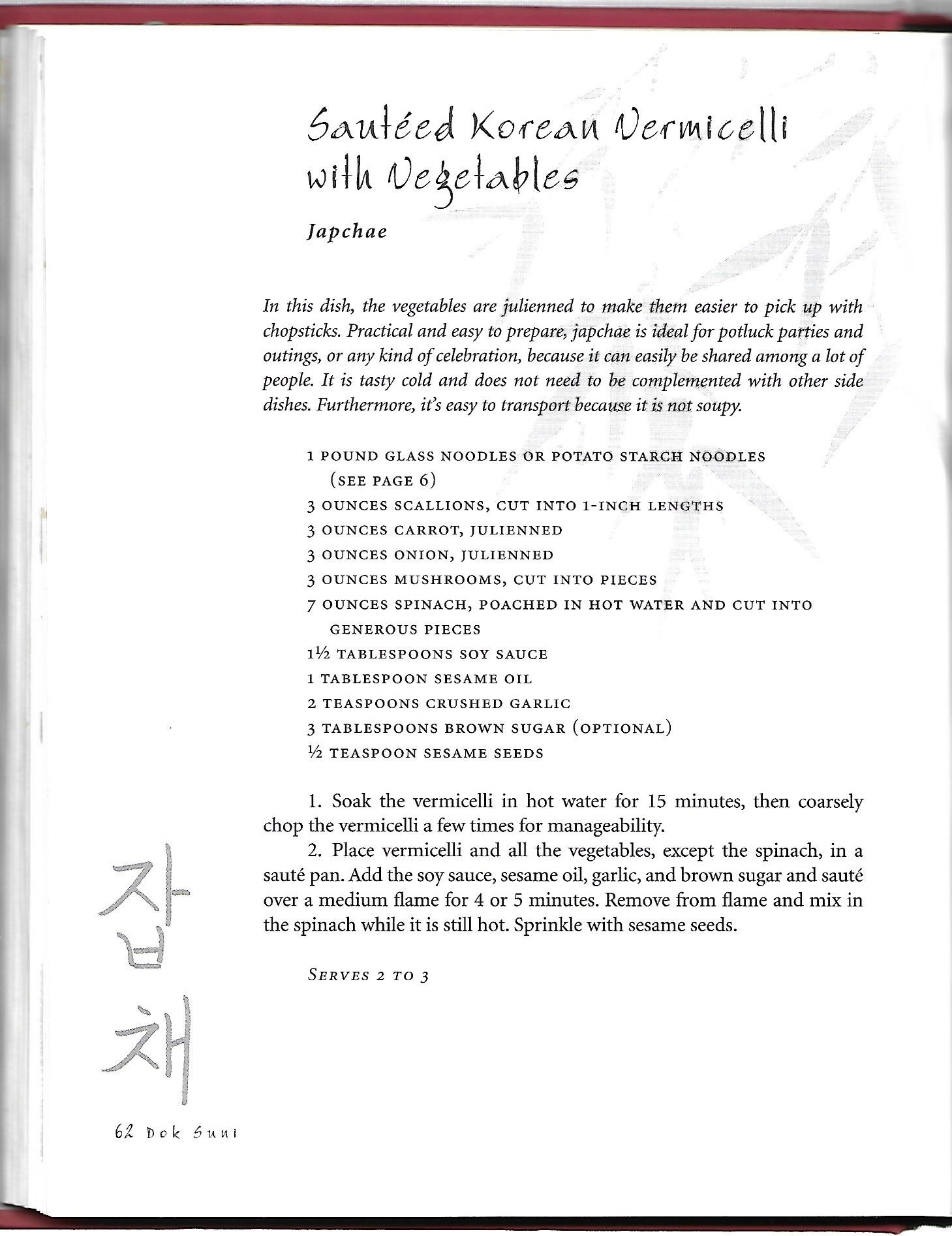

Setting the punch aside, I began prepping the vegetables for the japchae (잡채). As I re-read the recipe, I couldn’t help but take note of the stains and wrinkles that covered many pages of my family’s copy of Dok Suni. It occurred to me that the mark of a well-loved cookbook is the evidence that cooking leaves behind; evidence that the book cooked with you in the kitchen, that it’s lived with you.

There was something ruminative about doing the prep work, as strange as that may sound. But I think there is something to be said about taking the time to sit with your ingredients and the knowing of how that food is being prepared. There was an intentionality in the process that I found myself enjoying and reminded me of a quote from What We Hunger For: Refugee and Immigrant Stories about Food and Family; “When I’m cooking Haitian food, I am in communion with my mother, grandma, and all of my foremothers” (Shin & Déus, 2021). That’s what it felt like, alone in my kitchen, chopping ingredients in silence, the scent of cinnamon swirling in the air—it felt like I was standing there with my family, my ancestors. I could hear my parents’ advice as I julienned carrots and onions, my dad’s voice reminding me that mushrooms take longer to cook so I cut them thinner than I usually would. I wondered if my grandma’s hands moved in the same way as mine. I wondered who cooked for her before she could cook for herself.

The day of the Lunar New Year, I set to cooking at 3:30pm on the dot, music floating through the air to accompany me, the kitchen still smelling of cinnamon from the night before. My friends Sako and Jackson were coming over early, Jackson acting as my sous-chef for the night in his words. I was, and still am, unused to cooking with others in the kitchen, so I’ll admit I felt some trepidation at Jackson’s offer of help, but I also thought it’d be fun to share the space together. I’d only just finished soaking the sweet potato noodles in hot water and poaching the spinach when Jackson and Sako arrived. Jackson was quick to ask what I needed help with and I asked if he could get started on the prep work for the dak dori tang (닭도리탕) while I continued with the japchae. Sako took a seat across the island from me, Jackson setting up at the counter to my right, and the kitchen quickly filled with conversation overtop the softly playing music and knives against wooden cutting boards.

As we cooked, I pulled out the now-chilled ginger and cinnamon punch from the fridge and the three of us each had a glass. The punch had a thickness to it from the brown sugar, and we found that we needed to water our glasses down slightly, unused to such a strong taste of cinnamon. It was delicious though, and by the time the night was over the seven of us had almost finished off the punch.

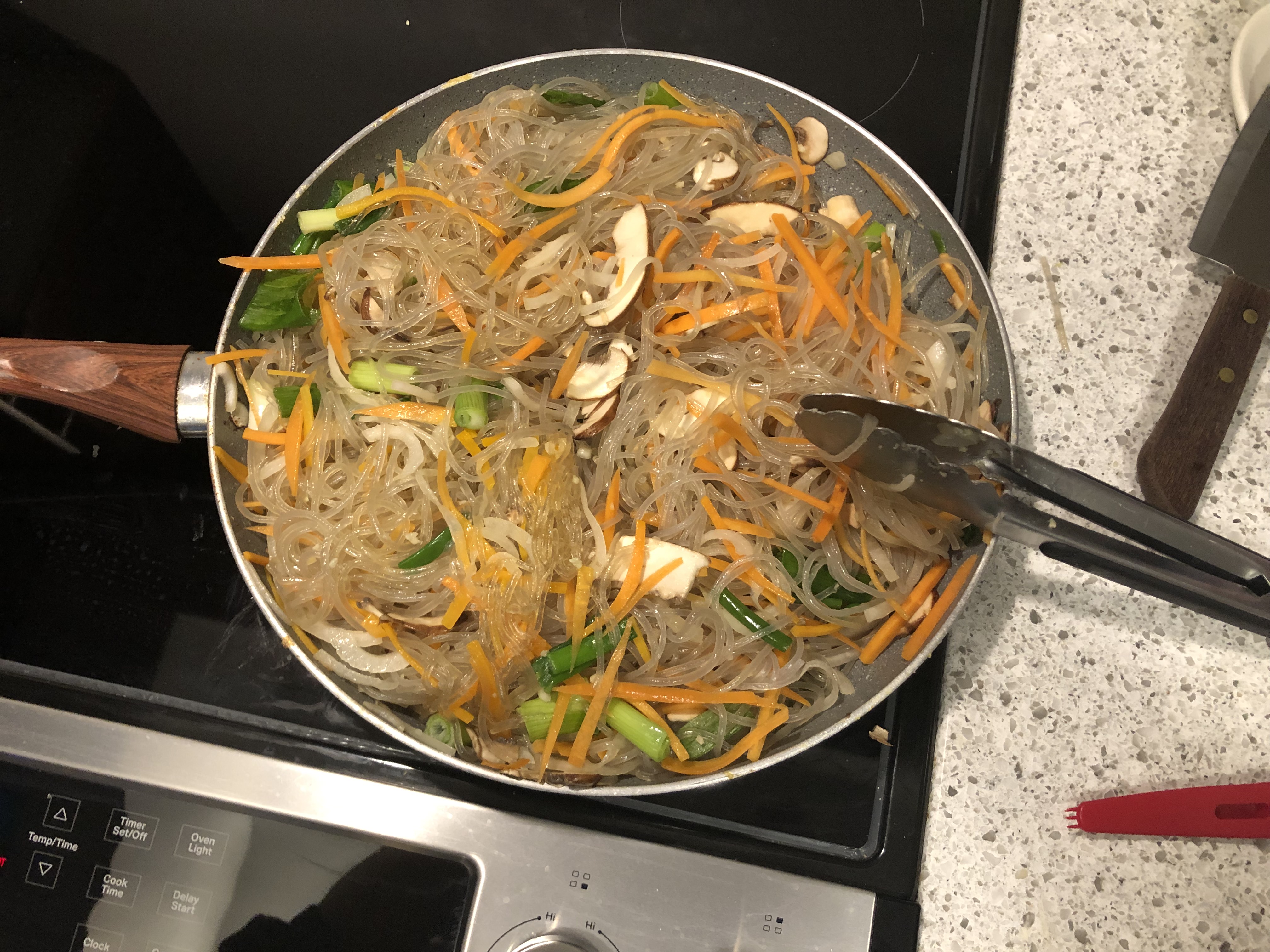

Throwing all the ingredients into the pan, I began to sauté the japchae. I worked carefully so as not to lose any ingredients from my admittedly overfilled pan. Luckily (or maybe unluckily) I have a distinct lack of a knack for gauging measurements which has given me much experience with cooking large quantities of food in a too-small pan, something that has exasperated my dad on many an occasion. But all went well and the dish tasted great. I found I like my homemade japchae more than the pre-packaged portions I’d buy from H Mart or Boo Han.

Next to go on the stove was the dak dori tang. Jackson has done the prep work, chopping and adding all the ingredients to a large pot. Following the recipe, I added one cup of water (we doubled the recipe) to the pot and placed it atop the burner, covering with the lid. We were all a bit skeptical that one cup of water would transform this dish into a stew that could feed seven people, but my sister cooked this a few times before back home without any issues, so I decided to trust the process.

Lo and behold, Jenny Kwak was right. When I removed the lid 20 minutes later, the contents of the pot had transformed into a stew. Taste-testing the broth, I was struck by the richness of it. Such a simple recipe, but it was bursting with spice, nuttiness, and depth. I felt contentment just from that one sip. To finish it off, I added the green onions as instructed, as well as my family’s own spin on the recipe; enoki mushrooms. The stew looked beautiful and tasted even better!

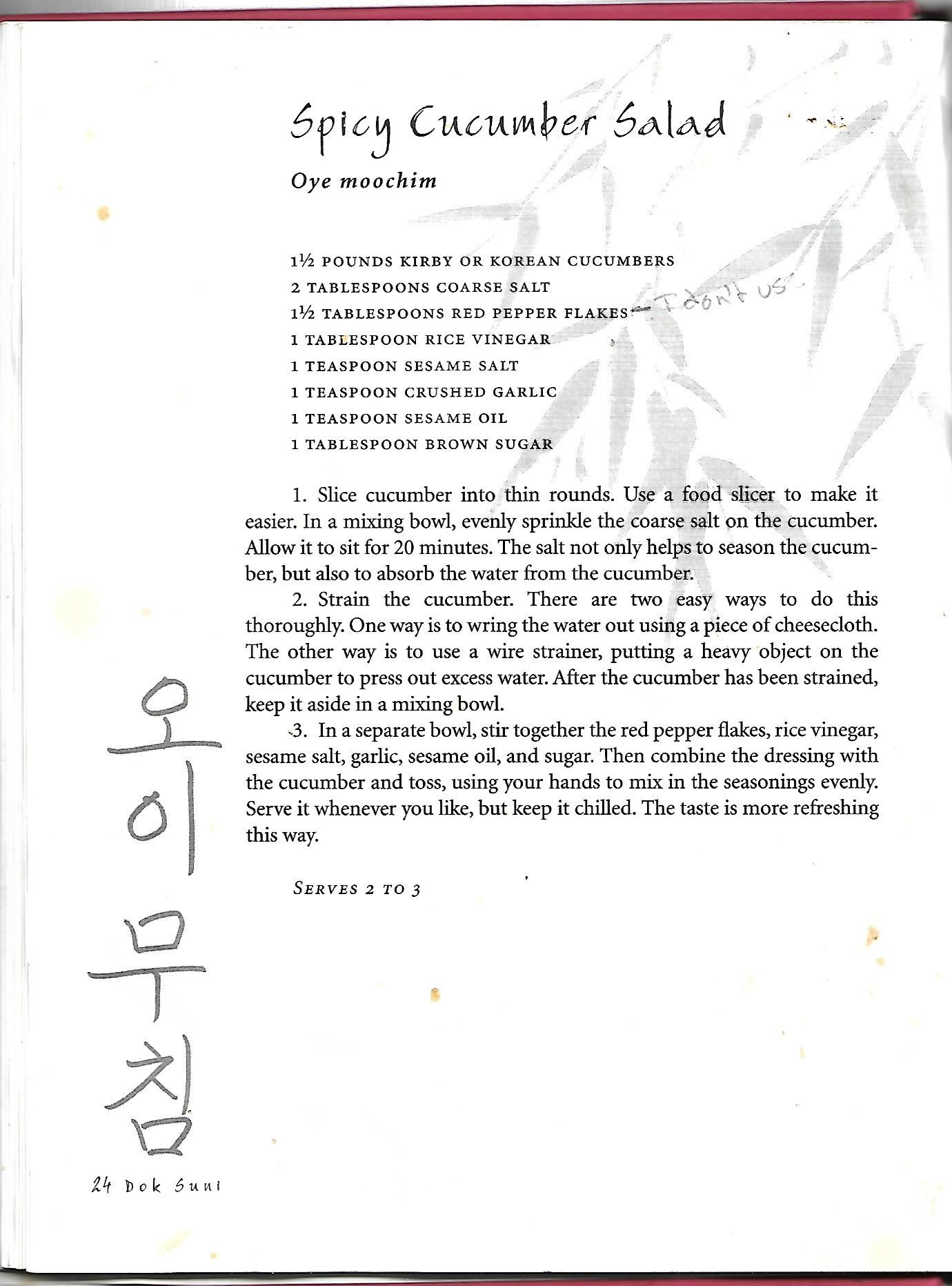

The next dish, which wasn’t planned, was an old favorite from my childhood. As a last minute addition, we decided to make spicy cucumber salad (오이무침). While Jackson sliced the cucumbers, I gathered up the rest of the ingredients needed. Although this recipe was familiar to me, I was used to my mom’s spin on it. As shown in the scan of the page taken from Dok Suni, you can see my mom’s handwriting, noting how she changed the recipe as well as some stains the page acquired from its years of use. While I was tempted to leave out the red pepper flakes and stick with what I knew, I figured if I was going to make the recipe for my ILC I might as well do it to a T. The result was, of course, delicious, the flavors fresh and crisp with a hint of that unique spice you can only get from Korean peppers.

Yes, this Lunar New Year was one filled with food and friends for me. I felt grateful to be able to share this part of myself with them and share my kitchen with them. I look forward to what I’ll cook next and am excited to continue sharing these dishes with my friends.

Be First to Comment