A: Natural history/regen ag research: mining bees, wood-nesting habitat

Mining bees of North America (Family Andrenidae)

Other facts:

- No built in thermal regulation, so they bask in the sun or on dark stones or burned areas.

- Don’t sting (Embry 2018)

Morphology:

- Medium-sized

- Relatively short-tongued

- Reddish gold hairs

- Long abdomens

- Skinny bods (Britannica 2018)

- Ranges between 8-17 mm

- Broad velvety faces (facial fovea)

- Long scopal hairs on the hind leg (Andrena 2021)

Range:

- Species native to the Columbia River Basin include Andrena aculeata (Shepherd 2004)

- As a genus, Andrena is worldwide in distribution. There are around 1300 species. (Andrena 2021)

Life cycle:

- One or two generations per year depending on sp (Britannica 2018)

- Females dig nests (Embry 2018)

- Usually like sandy soil and shrub cover.

- Emerge in spring, mate, and then dig burrows, forage, lay eggs in cells. (Andrena 2021)

Nesting habits:

- Solitary, but often aggregated

- Dig ground tunnels in which cells are individual branches from a main tunnel

- Stocks with pollen balls and nectar (Britannica 2018)

- 6-7 inches deep

- A minority of species will sometimes share a “front door” and dig lateral tunnels for their individual nests

- Commonly nest in lawns (Embry 2018)

Forage plants:

- Use flight muscles to buzz-pollinate plants like blueberry and tomato

- Clover (Embry 2018)

- Andrena fragilis, A. integra, A. platyparia are dogwood pollen specialists (Gill 2018)

- Apples (Wheeler 2016)

- Rose family

- Brassica family (Wood and Roberts 2017)

Phenology:

- Emerge in early spring (Wheeler 2016)

Agricultural significance:

Andrena bees can be great allies in an orchard if the trees are suitable for short-tongued bees. Apples are one example. Because the ground is not tilled, they can make homes very close to the trees. They deposit 2 to 3 times more pollen than honey bees (Wheeler 2016).

Pests and disease:

- Nomada parasitic bees (Embry 2018)

Species spotlight:

Andrena aculeata, one of our native mining bees, is active May to August. It forages on a range of species (indicated by it’s range) and has been recorded in subalpine fir and spruce forests, as well as agricultural landscapes (Shepherd 2004).

Wood nesting habitat

- Pithy or hollow woody plants:

- Elderberry

- Sumac

- Hydrangea

- Currant

- Raspberries

- etc

- Snags, AKA dead or dying trees

- Fallen logs

- Avoid completely pruning perennial shrubs in winter! (Project Dragonfly)

Left: a salmonberry stem which I cut and poked at

B: Habitat assessment/improvements:

Did not attend Tuesday.

Planting in the garden:

- Echinacea

- Purple aster

- Yarrow (native)

- Calendula

- Borage

- Strawflower

Planted stuff on thursday, also took down observations for wood nesting habitat section. I got strawflower and purple aster transplants in the ground as well as moved some oregano and columbine to their permanent home with space to spread.

The community gardener with the plot next door wants to rehome the chives, and Ashley plans on using the rest of the bed I’m working on to plant sunflower (great late-summer forage for bees!).

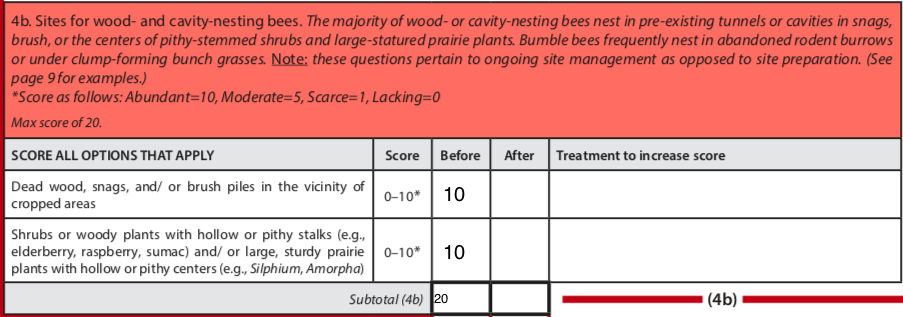

Assessment: wood nesting habitat

Hollow and pithy plants at the farm:

- Nootka rose

- Elderberry

- Currant

- Raspberry

- Salmonberry (is this really hollow? check)

There is also an abundance of dead wood in the forest surrounding the farm, and various stumps within the borders.

C: Film and media analysis: the pollinators film notes

Starting at minutes 9:30 Susan E. Kegley, Phd, says that honey bees are integral to the system which produces cheap food. This means the honey bees are in an area that’s treated with pesticides, and also monocropped with only one type of flowering plant in usually a large area, leaving few wildflowers. The Film makers pan over an almond orchard which extends to the horizon. “Once the crop has bloomed, there’s nothing there for the bees to eat”, Susan says. They explain that this is why the honey bees have to move around. “The managed honey bees have the beekeeper helping them survive…the native pollinators are in deep trouble because they can’t move away from agriculture.” Here the filmmakers use some beautiful close ups of bumble bees and small bees foraging on wildflowers.

I think this really captures the difference between “saving” the honey bees and “saving” the wild/ native pollinators. Both are at this point integral to our food systems, but wild bees represent ecological realities much farther outside human control than domesticated bees. Domesticated bees can be studied closely, managed individually, their issues bandaid-ed by technology or small changes for some time. To conserve native pollinators, we have to make fundamental changes to land management.

D: Tasting research: jun, or honey kombucha

What is Jun?

The origins of Jun are not known, though Sandor Katz in their book The Art of Fermentation infers that it’s probably just a recent spin on Kombucha. Kombucha is likely from China (LaGory and Katz 2017). Jun is brewed with green tea and honey, using a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) (Codekas 2015).

Health benefits of Jun?

There is no specific research on Jun itself, but green tea and honey have health promoting qualities. Green tea is high in antioxidants, vitamin C, theanine, γ-aminobutyric acid, and caffeine. Also, the tea catechin EGCG is considered to be associated with “anti-cancer, anti-obesity, anti-atherosclerotic, anti-diabetic, anti-bacterial, anti-viral, and anti-dental caries effects” (Suzuki et al 2012).

The effects of honey on human health vary with environmental factors and floral origin (terroir if you will). It contains water, fructose, and glucose. All honey has antibacterial properties but this dilutes when met with bodily fluid (Ellis 2014, Albaridi 2019). It may also include various quantities and kinds of complex sugars, minerals, vitamins, proteins, phytochemicals and beneficial enzymes (Ellis 2014). Honey also contains the enzyme glucose oxidase which can sometimes break down glucose into hydrogen peroxide, but not if heated (Ellis 2014). Honey has been used topically or on wounds, and when paired with plant medicine can help make compounds bioavailable by breaking the cell walls of the plant (Ellis 2014).

Sensory analysis of Jun?

I couldn’t find much information on the sensory analysis of Jun specifically, and from what I can tell there is no official sensory analysis of Kombucha outside of individual companies. There are some tasting rooms for Kombucha, such as the Seattle Kombucha Company’s.

I made a flavor wheel combining the honey flavor and aroma wheel from The Honey Connoisseur, and the tea flavor wheel from Kuan Yin Teas, which was used at the winter 2021 Lunar New Year tea appreciation.

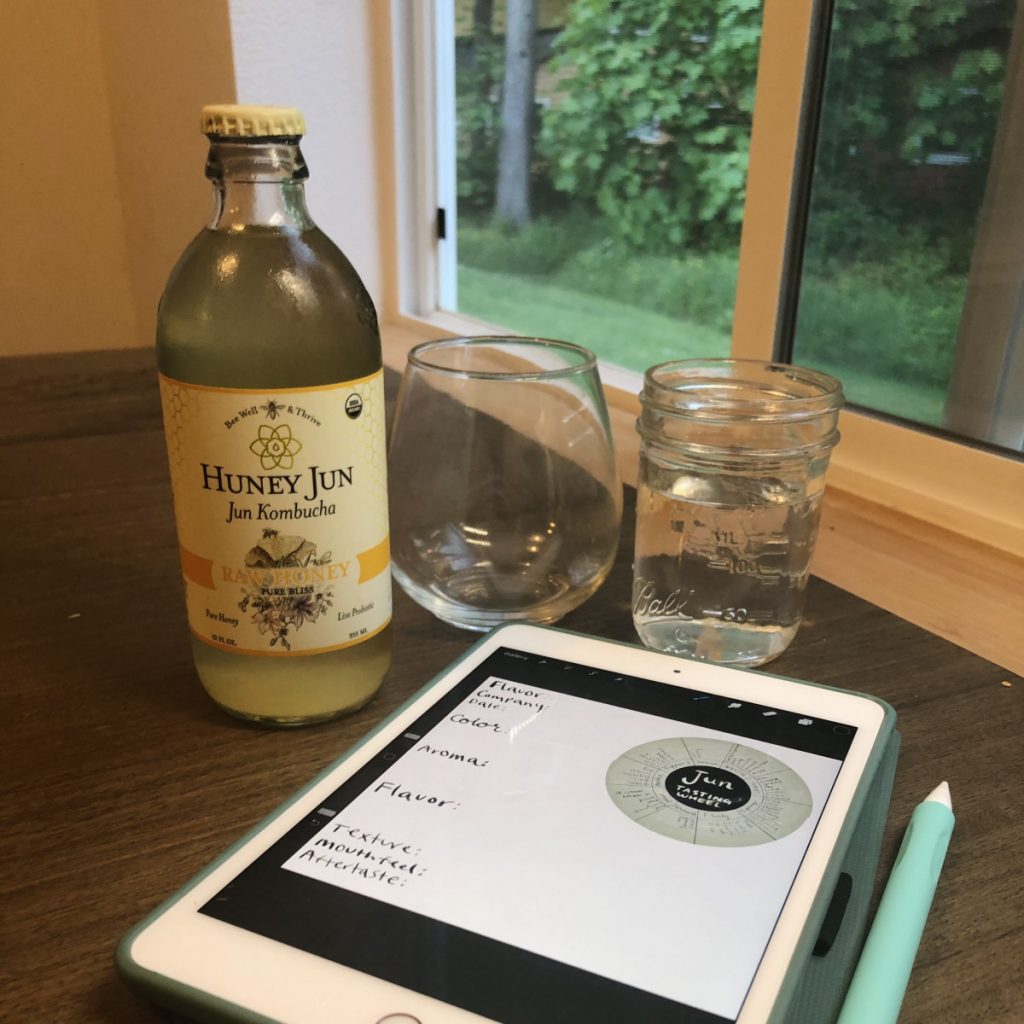

E: Sensory analysis: tasting jun

I only bought one flavor to try. I used the wheel I drew and my own form similar to other sensory analysis forms we’ve used. I sat by the window with a glass of water and took down observations while I tasted.

F: Special events: Ecologies of Power talk

Bam’s talk was surprisingly therapeutic. I’m not sure what I expected, but I really enjoyed sharing a space with people who like understanding themselves and others through ecological metaphors. Someone contributed the idea that capitalism tries to make us rush all the time, but some of us are slugs or even moss.

G: Cooking

With my leftover mead, I made a sweet and tart dressing with whatever I could find, which ended up being:

- 1 tsp mead

- 1 tsp white vinegar

- 1 tsp olive oil

- Garlic

- Salt

- Pepper

- More honey to taste

I tossed it on some crisp, fresh, bitter greens grown by classmates at the community gardens. I added honey goat cheese and carrot slices. My partner and I loved it.

I also found an awesome book to read that is not a foodoir exactly, but is about North American bees and the authors journey learning to appreciate what they do, Our Native Bees by Paige Embry. So mad I didn’t find this book sooner, but I can read it before the quarter ends. Their communication style is inspiring to me. The voice of their writing is friendly and authentic, but they get a lot of information across.

A couple of quotes I enjoyed:

“Tomatoes require a special kind of pollination called buzz pollination, where a bee holds onto a flower and vibrates certain muscles that shake the pollen right out of the plant. Honey bees don’t know how to do it, but certain native bees do. I was appalled. How could I, a serious gardener for many years, not have learned that it takes a native bee—not a European import—to properly pollinate a tomato?”

“Pollen is rich in proteins, amino acids, and fats, with some carbs thrown in as well. It’s great baby food. Pollen also happens to be the flower’s equivalent of sperm, setting up a fine opportunity for a mutually beneficial relationship.”

Plants and bees teach us reciprocity. Bees are evolved to pollinate flowers, and do little else, with some outliers with bad manners who “break in” to flowers. Bee-pollinated plants evolved flowers perfectly suited for bees’ bodies. The right bees’ bodies, like tomato making himself enticing to the (also American native) buzz-pollinators. Both insect and flower give a gift to the other, who uses it to reproduce and multiply the value of that gift, while feeding the rest of their ecological community too. Each generation continues the relationship.

H: References

2. Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2018, February 2). Mining bee. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/animal/mining-bee

3. Embry, Paige. (2018). Our native bees: North America’s endangered pollinators and the fight to save them. Portland, OR. Timber press

4. Gill, K. (2018, May 15). From the field: trees for bees. Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. https://xerces.org/blog/from-the-field-trees-for-bees

5. Wheeler, J. (2016, October 7). Celebrate apples by celebrating their pollinators. Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. https://xerces.org/blog/celebrate-apples-by-celebrating-their-pollinators

6. Shepherd, M. (2004, November 16). Mining bees. Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. https://xerces.org/endangered-species/at-risk-bees/andrena-aculeata

7. Andrena. (2021, May 12). In Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrena#cite_note-1

8. Wood, Thomas J.; Roberts, Stuart P. M. (2017). “An assessment of historical and contemporary diet breadth in polylectic Andrena bee species”. Biological Conservation. 215: 72–80. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.09.009. ISSN 0006-3207.

9. LaGory, A. Katz, S. E. (2016). The big book of kombucha. North Adams, MA. Storey Publishing, LLC.

10. Katz, S. (2012) The Art of Fermentation. Hartford, VT. Chelsea Green Publishing.

11. Codekas, C. (2015, October 18). How to brew jun kombucha. Grow Forage Cook Ferment. https://www.growforagecookferment.com/how-to-brew-jun-kombucha/

12. Suzuki, Y., Miyoshi, N., & Isemura, M. (2012). Health-promoting effects of green tea. Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and biological sciences, 88(3), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.88.88

13. Ellis, H. (2014) Spoonfuls of honey. London, UK. Pavilion Books.

14. Albaridi, N. A. (2019). Antibacterial Potency of Honey. International journal of microbiology, 2019, 2464507. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2464507

15. Tran, T. Grandvalet, C. Verdier, F. Martin, A. Alexandre, H. Tourdot-Maréchal, R. (2020) Microbiological and technological parameters impacting the chemical composition and sensory quality of kombucha. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 19: 2050– 2070. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12574

16. Nesting habitat. Project Dragonfly. https://projectdragonfly.miamioh.edu/great-pollinator-project/management/nesting-habitat/#:~:text=Cavity%20nesters,hydrangea%20from%20year%20to%20year.