6a. Natural history/regen ag research

Ground nesting habitat

Most North American bees nest in the ground, 70% (Code 2019). Some, including bumble bees, nest in ready-made crevices like rodent burrows, while others such as sweat bees dig their own tiny tunnels. Various species use plant material or secretions to line the walls of their nests, in order to keep out pests, disease, and even excess moisture. Like honey bees, ground-nesting bees lay their eggs in individual cells with provisions of pollen and often nectar. These cells may be constructed in a variety of ways. Most ground nesting bee species are solitary, though some are social. Still others are somewhere in between, either nesting in aggregates or showing a range of behavior depending on circumstances. (PennState 2021) They like sunny, bare, well-drained soil. South facing slopes are best, in which case you should plant some short grass or other sparse cover to prevent erosion. Don’t till this area any time of year. Don’t spray pesticides. (Code 2019)

Native bee spotlight: sweat bees AKA Halictid

These insects are called “sweat bees” because they drink sweat from farmers to obtain salt. (TEDxTalks 2015)

Taxonomy

Family: Halictidae

Distribution

Present in various parts of the world. Species native to Western North America (Wilson-Rich 2014)

Sunflower Sweat Bee (Dieunomia triangulifera)

- Black and brown, 9-15.5 mm, stout bodies

- Commonly found on sunflowers (which I planted in community garden) in agricultural landscapes

- Forage in late summer

- Females only live for 13 days

- Males emerge before females and disperse to mate with emerging females

- Females then work on nesting, foraging, and laying brood (2-6 offspring)

- Nest in aggregations of 40 nests in “moist, compacted soil in bare open fields, between rows of crops, in field margins, and on roadside verges” (Wilson-Rich 2014)

- All activity happens in August-September

Augochlorella aurata

- Morphology: skinny with wide faces, metallic iridescent green body, golden-white hairs, 5-6 mm

- Forage: Opuntia, Polygonum hydropiperoides, Viburnum rufidulum, Rubus, and Aster (planting next week)

- Life cycle: Two consecutive broods: first is workers that help rear the second brood, which is fertile males and females. They mate in late summer and surviving “queens” (fertile females) overwinter. Sometimes sister “queens” are born who divide tasks. Daughter foragers can become fertile if queen dies early.

- Nesting: “primitively eusocial” (Wilson-Rich 2014) in aggregations in grassy embankments or south-facing slopes. 7 eggs per nest.

- Phenology: May to November

- Location: grasslands and urban areas, Canada to Mexico, Pacific coast to East lowlands.

- Smallest and most abundant North American sweat bee (MI Dept of Conservation 2015)

Morphology

- Most are skinny, some are more stout (Buckley et al 2011)

- Carry pollen on legs (Buckley et al 2011)

- Black, green, blue, and/or purple (Buckley et al 2011)

Life cycle

- Make pollen balls for babies (TEDxTalks 2015)

- Most overwinter as fertilized females rather than pre-pupae (Buckley et al 2011)

Nesting habits

- Ground nesting (TEDxTalks 2015) or rotten wood (Missouri Department of Conservation 2015)

- In both cases, they dig tunnels (Buckley et al 2011)

- Some are parasitic, stealing others’ nests (Buckley et al 2011)

- Most need exposed soil and nearby forage (Buckley et al 2011)

Forage habits

- Individuals are very generalist, making them not very effective pollinators when diverse resources are available (depends on time of year) (Tepidino)

- Gumweed is popular with sweat bees, which I planted in the garden (Adamson et al 2014)

- Ocean Spray is also known to be visited by sweat bees, which is also growing at the farm (Adamson et al 2014)

Phenology

- Active April through November (see specific species for phenology in PNW) (Buckley et al 2011, Wilson-Rich 2014)

Agricultural significance

- Known to pollinate stone fruit, pomme fruit, alfalfa, and sunflower (Buckley et al 2011)

Social life

- Aggregate in groups of 10-20 individuals (TEDxTalks 2015)

- Females decide who is queen by fighting (submissive becomes infertile) (TEDxTalks 2015)

- Very socially plastic depending on the species and even environment (Buckley et al 2011) which may make them highly adaptable to climate change (Schürch et al 2016)

- Can be solitary, communal, semi-social or eusocial (Buckley et al 2011)

- Queens will sometimes work together to rear young, in which case only one lays eggs that year (MI Dept of Conservation 2015)

What can you do for these agricultural allies?

Follow advice from conservationists on ground-nesting bees in general (summarized above) as well as planting forage that sweat bees like.

6b. Habitat assessment/ improvements

Farm journal

Tuesday 5/4: Caleb cut down the mustard flowers, so I saw far less bees, but still some! Strawberries and onions are flowering. I installed a borage plant, although it’s not doing great. Some of the seeds I planted are coming up. Did lots of noxious weed removal (mustard, alkanet, comfrey, buttercup). Gave some calendula seeds to Alegra.

the new plan with the community garden plot is that I’ll:

- Remove noxious weeds from at least the fence-side half.

- Rescue non-invasive things (onion, tulip, lemon balm, strawberry, etc) from the path-side half, and move them to the fence-side half.

- Label and make paths to create a (potentially temporary) mini pollinator garden.

On Thursday morning 5/6, I walked around the farm to photograph each species of clump-forming grass I saw, as well as note on the map where bunching grasses were abundant, and where there was apparently little ground disturbance. I’ll need to talk to someone next week about mowing and tilling to get a better idea of the habitat for ground-nesting bees.

I also weeded another section of my community garden bed so it is ready for planting or relocating existing plants.

Assessment notes

INSERT photos of grass species, AND ASSESSMENT PAGE

6c and d. Film and media analysis tasting research

I couldn’t find a ton of audio/visual media around mead. I did find The Mead Podcast and a video about Superstition Meadery in Arizona.

In the Mead Podcast episode 3, The History of Mead, they discuss where mead comes from, why it died out as an art, and why it’s made a come back. Mead is very old because it happens naturally sometimes when the curing process of nectar is disturbed by flooding or uncapping too early. Mead making can be traced back as far as ancient mesopotamia and evidence of it exists in greece, rome, celtic culture, etc.

The reasons it fell out of favor in england specifically (the podcast is recorded there), is because of mead becoming a less desirable, working-class beverage, as well as the introduction of hops and distillation displacing other brewing practices. Honey is a very expensive product to brew with.

From minutes 6:40 to 8 Tom shares what he thinks are the reasons for mead’s revival, which is mostly going on in the U.S. He talks about mead’s appeal to fans of craft brewing. He says, “people are looking for new products that are interesting, well-crafted with a real sense of provenance, and mead fits all those bills. You can get this real sense of terroir and craftsmanship out of a really good mead.”

Sensory analysis of honey and mead is a relatively new thing. The International Honey Commission was established in 1998 to develop standard protocol for analyzing honey for defects and floral origin. While lab testing can determine some of these things, inconsistency in flavor is only detectable by sensory analysis (Piana et al 2004).

6e. Sensory analysis

I bought a bottle of “Tastes Like Sunshine” mead by local Olympia Axis Meadery, which is described on their website as “the sweetness of clover blossom accentuated by the sweet-tart flavor of Blood Orange.” I’m excited to try it. Axis Meads was started in small batches by Skep & Skein Tavern co-founder Dave Ross, and scaled up when people showed interest. It was the only mead I could find at Bayview Thriftway downtown.

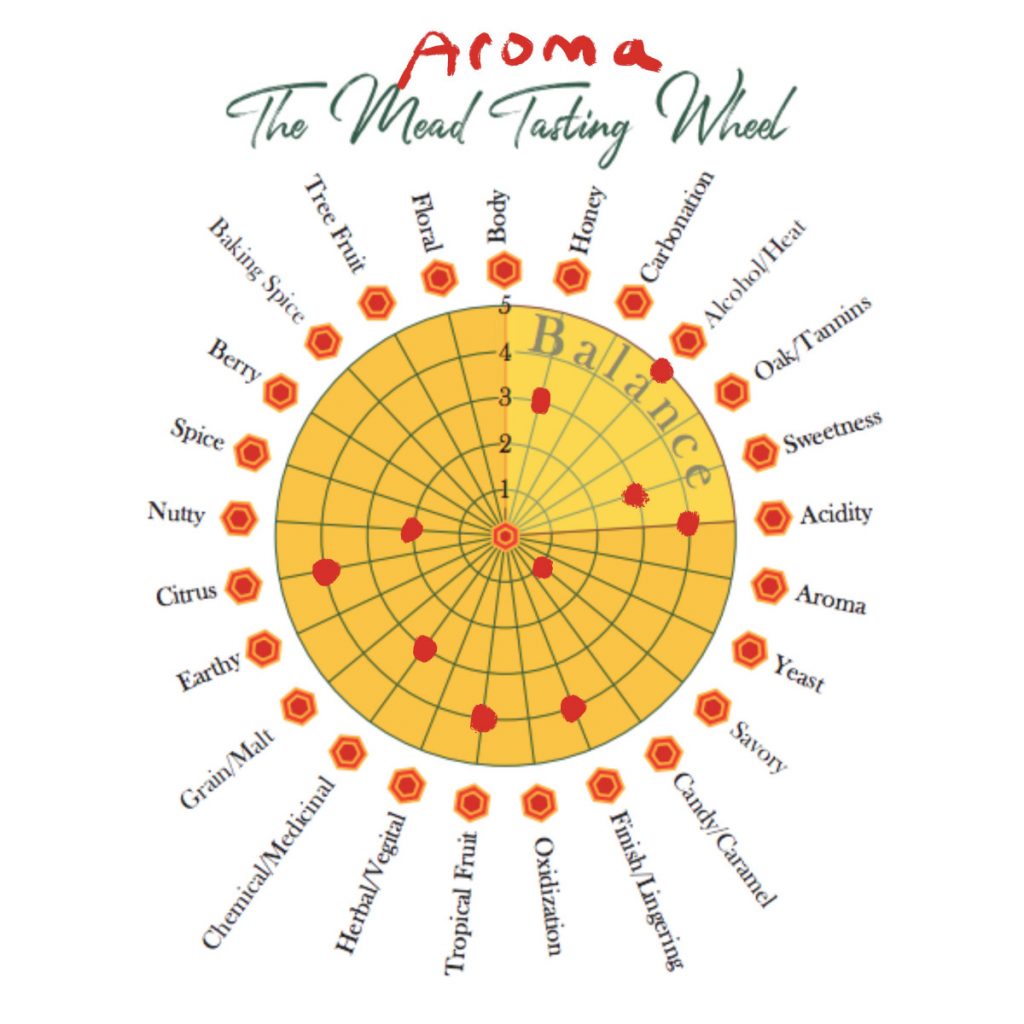

I’ll be using this tasting wheel from woman-owned Sky River Mead in Redmond, WA. There were various mead lexicons and visual tools available, but this one I chose because it was created for a more casual tasting experience rather than professional analysis.

INSERT PHOTOS AND NOTES FROM TASTING

6g. Cooking

H: References

1. TEDxTalks. (2015, May 16). The secret lives of native bees, Dr. Sandra Rehan, TEDxPiscataquaRiver [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F255KADo0Ao

2. Tepidino, V. Halictid bees. USDA. Link

3. Adamson, N. L. Borders, B. Cruz, J.K. Jordan, S. F. Gill, K. Hopwood, J. Lee-Mäder, E. Minnerath, A. Vaughan, M. (2014). Pollinator plants: maritime northwest region. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

4. Wilson-Rich, N. (2014). The bee: a natural history. Sussex, UK: Princeton University Press

5. Missouri Department of Conservation. (2015). Sweat bees. Conservation Commission of Missouri. Link

6. Schürch, R., Accleton, C., & Field, J. (2016). Consequences of a warming climate for social organisation in sweat bees. Behavioral Ecology & Sociobiology, 70(8), 1131–1139. https://doi-org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s00265-016-2118-y

7. Buckley, K. Nalen, C. Z. Ellis, J. University of Florida. (2011, August). Sweat or Halictid bees. Featured Creatures. http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/bees/halictid_bees.htm

8. PennState College of Agricultural Sciences. (2021). Nesting sites. Department of Entomology. Link

9. Code, A. (2019, June 20). Remember the Ground Nesting Bees when You Make Your Patch of Land Pollinator-Friendly. Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Link

10. Senn, K. Cantu, A. Harris, A. Heymann, H. (2020) Catalyst: Discovery into Practice 4:91-97; DOI: 10.5344/catalyst.2020.20005

11. Piana, M. L. Persano Oddo, L. Bentabol, A. Bruneau, E. Bogdanov, S. Guyot Declerck, C. (2004). Sensory analysis applied to honey: state of the art. Apidologie, 35 (DOI: 10.1051/apido:2004048). https://www.bjcp.org/mead/MHS05.pdf

12. MacKinnon, A., Pojar, J., & Alaback, P. B. (1994). Plants of the Pacific Northwest coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska. Richmond, Wash: Lone Pine Publishing.