5a. Natural history and habitat research

Fun fact: bees find floral resources via olfaction, sometimes by communicating scents between social bees antenna-to-antenna if good food is located. (Wilson-Rich 2014)

Native bee spotlight: leaf cutter bees (Megachile)

Morphology

- 10-20 mm

- Broad heads and enlarged mandibles

- Upturned abdomen (Young et al. 2016)

- Leafcutter bees (Megachile) belong to Megachilidae family with mason bees due to the lack of leg pollen baskets. Pollen collects on abdomen

- About the size of a honey bee

- Mostly black and furry, with a yellow belly

- Use mandibles to cut leaves (6)

Life cycle:

- Emerge in spring, soon mate

- Males die not long after

- Females look for nesting

- Mother makes bee loaves out of nectar, pollen, and saliva (which may contain antifungal and antibacterial elements) mixed together for brood

- She lays an egg on top of a large enough loaf, and wraps it in chewed leaves

- She puts all these bundles of eggs and loaves into the cavity until full, then seals it with an extra wall, and dies.

- They are so called bc they cut petals and leaves for building cocoons. (6)

Range:

- 29 known native species in Washington

- Arctic-tropical, sea level to 5,000 ft

- 131 species native to US

- deserts, coastal dunes, prairies, shrublands, gardens, and openings in forests.

- Forests with dense canopy are not ideal, lacking in broad leaves for construction

- 28% of north american species are endangered. Causes:

- Habitat loss

- Invasive species dominance

- Disease

- Pesticides, particularly systemic (Young et al. 2016)

- Habitat loss

Nesting

- Leafcutter bees take well to artificial nests, so are used industrially in agriculture (Wilson-Rich 2014).

- In between stones

- In earthen riverbank substrate

- Like mason bees, females are placed in the back (Young et al. 2016)

- Some form small colonies (semi-social)

- Most are solitary

- Nest in small wood cavities or in hollow stalks

- Some nest underground

- Pencil wide cavity

- You can make one out of bundles of tubes or drilled holes, like mason bees! (6)

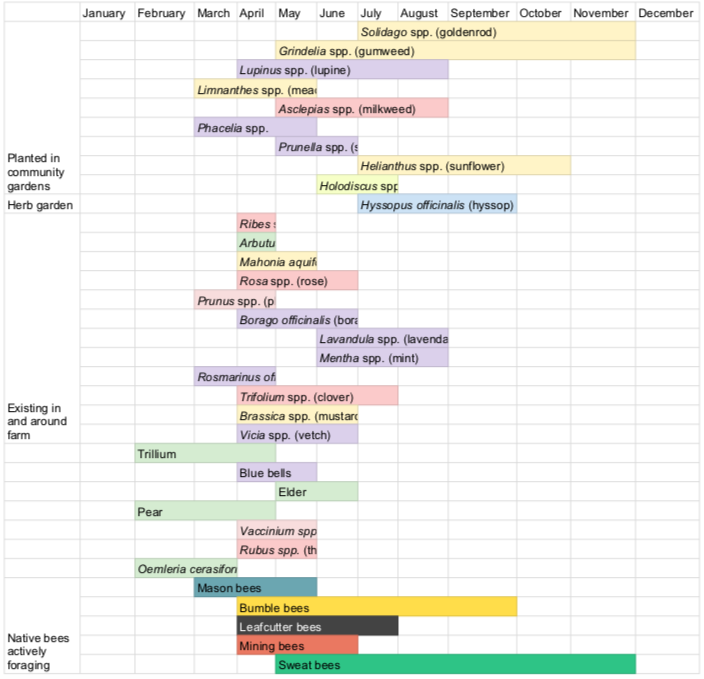

Phenology:

- Forage and nest in late spring/ early summer (right now!) (Young et al. 2016)

Forage:

- Aster family (Asteraceae)

- Pea family (Fabaceae)

- Late spring and summer blooming

- Specialists:

- Oenothera spp. visits evening primrose

- M. davidsoni specializes in golden eardrops (Ehrendorferia chrysantha)

- Red clover

- Blueberry

- Alfalfa leafcutting bees, though not native to North America, have proven the potential for leafcutting bees to be very efficient and fill the economic niche of honeybee pollination

- M. perihirta and M. dentitarsus are native canadian leafcutting bees that work well in cold and pollinate alfalfa also (Young et al. 2016)

Nesting habitat needs:

- Leaves for cutting

- Pithy or hollow stems

- Resin bees, a subgroup of leaf-cutting bees, only nest in holes made in wood by other insects (Young et al. 2016)

Threats or predators:

- Parasites

- Wasps

- flies (e.g., Anthrax species)

- Beetles

- Other species of bees.

- Mites (Young et al. 2016)

Though not much data is available on leafcutter bees due to lack of research, one example of a native Washington leafcutter bee is Megachile melanophoe who is known to forage on Agastache, Apocynum, Astragalus, Azalea, Campanula, Cypripedium, Epilobium, Helianthus, Lupinus, Medicago, Phacelia, Psoralea, Ranunculus, Raphanus, Rhodora, Rosa, Rubus, Rudbeckia, Symphoricarpos, Taraxacum, Trifolium, and Vicia.

Bee health

Bees don’t build up antibodies, rather, they employ physical, cellular, and some humoral immunity (using enzymes and other compounds). Bees are affected by many different fungi, bacteria, viruses, and arthropods, which is especially problematic when the the pest or pathogen is introduced/ non-native (Wilson-Rich 2014). Abundant and diverse forage that provides a variety of nutritional services is important to the resilience of populations (Wojcik 2018).

Fungi:

- Common giving that bees often nest in dark cavities

- Nosema is a common one

- Fungi can directly affect bees or affect their nests

Bacteria

- Causes higher colony loss than fungi

- Is acquired orally and affects the gut

- May go away or spread to other nests

Virus

- Transmissible directly or via arthropods

- Often has visible symptoms

Arthropods

- Example, Varroa mite, which carries viruses

- Beetles

- Mites

- Moths

- Usually invasive species (Wilson-Rich 2014)

5b. Habitat assessment/improvements

Planting

Talked to Sarah D, decided to collaborate on clearing noxious weeds out of the abandoned kale bed, leaving herbals, strawberries, flowers, and adding seeds in the empty patches. I spent some time Tuesday and Thursday weeding the community garden bed. I also plan on sowing some dually medicinal and bee-food plants in the empty areas after clearing weeds, probably in week 6.

Spotted: lots and lots of bumble bees

Assessing

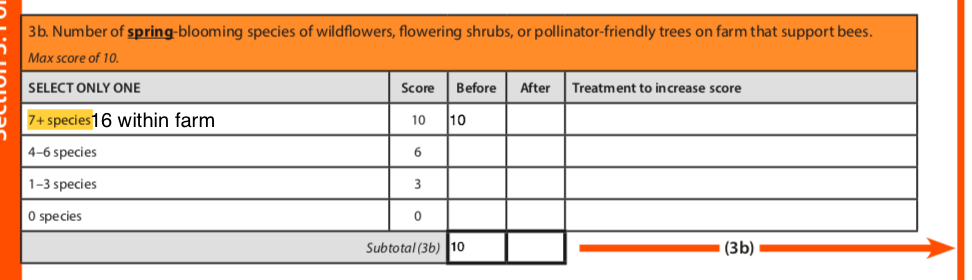

On tuesday I walked up and down the farm inventorying “spring-blooming species of wildflowers, flowering shrubs, or pollinator-friendly trees on farm that support bees” (Adamson et al. 2015), not including noxious or invasive plants.

Around the farmhouse and other buildings

- Pacific dogwood

- Black huckleberry

- Salal

- Red dead nettle (naturalized)

- Cascade barberry

- Red huckleberry

- Pacific crab apple

- Osoberry

- Annual honesty (naturalized)

- Bleeding heart

- Red clover (naturalized)

Within the farm fence

- Trillium

- Red-flowering currant

- Blue bells

- Red-berried elder

- Pear

- Candy flower

- Chokeberry

- Apple

- Plum

- Cherry

- Oregon grape

- Oceanspray

- Salmonberry

- Osoberry

- Red huckleberry

- Borage (non-native but not technically invasive, unlike relatives)

In the road-side insectary shrub garden

- Yellow-flowering currant

- Serviceberry

Trillium

Red clover (naturalized)

Salmonberry

Pacific dogwood tree

Cascade barberry

Huckleberry

Purple/red dead nettle

Pacific crab apple

Annual honesty

Pacific bleeding heart

North american blue bells

Serviceberry

Chokeberry

Red huckleberry

Red-flowering currant

Borage

Red-berried elder

Yellow currant

Apple tree

Invasive/noxious species in the farm and around buildings

- Comfrey (which the bees seem to love, but I wonder how that affects other plants?)

- Buttercup

- Mustard

- Pentaglottis/forget-me-not

- Dandelion

- Dove’s-foot crane’s-bill

- Periwinkle

- Daisy

- Carpet bugle

Buttercup

Comfrey

Forget me not

Mustard

Periwinkle

Alkanet

Dovesfoot crainsbill

Daisy

Carpet bugle

5c. Film and media analysis

In this clip, Ed Szymanski explains his reasons for growing medicinal and culinary herbs as a beekeeper. He says that growing herbs is “extremely beneficial” to the pollinators. He cites evidence that honey bees prefer forage with antimicrobial properties. He also points out that growing herbs is also good for human health.

Some of the benefits that bees get from the flowers they feed on include:

- Ex: thymol from thyme deters varroa mites

- Honey bees prefer to forage on antimicrobial plants especially if ailments are present

- Bees are excellent at self medicating via forage, and even transfer some of those qualities to honey

- Ashley Adamant: help the bees, help yourself

- Rather than veggies for us, flowers for bees, plants that do both!!

- Carvacrol

- Thymol

- Terpenes

- Antimicrobials

- Palmitic, linoleic, linoleic acids

- Borage, sage, thyme, cham, sunflower (all also antibacterial)

The idea of planting farmscape pollinator habitat that also provides herbal food and medicine to people (for either commercial or personal use) is exciting to me. I imagine that planting herbs for native bees could be a source of income that would incentivize creating habitat for feral native bees rather than keeping honey bees.

He says that some excellent plants for this practice are:

5d. Tasting research

Monofloral versus polyfloral honey

- Many commercial beekeepers sell honey and migratory pollination services for intensive monocultural farms

- They harvest multiple times a year and typically offer moonofloral honey because of the market value of that

- Most, though, are small beekeeping operations.

- Many harvest only once a year, yielding complex honey which contains aggregate flavors from across seasons, often labelled “wildflower”

- Some harvest multiple times a year, yielding flavor profiles specific to each season

- Spring is light, summer is typically darker, and fall (if there is any) is super dark and rich

- If there is one dominant species in the time between harvests when bees are actively foraging, it might be obvious the primary source of nectar

- In this way, there are “specialized” and “generalist” honey peddlers

- Honey flavor is a reflection of the beekeepers, the climate that year, and the floral resources in the local area

- Climate change

- Extreme weather events can cause changes in overall flavor and appearance

- (Marchese, Flottum 2016)

5g. Cooking

This week, on the theme of sharing food and herbs with the bees, I made some mustard flower spring rolls (with homemade honey peanut dip of course), lemon balm tea, and a little fresh oregano on my pizza, all of which I picked in the overgrown community garden bed.

Topped the red one with marinara, moz, spinach, canned artichoke, and spicy honey I brewed on the stove.

Topped the plain one with fig balsamic vinegar, goat cheese, walnut, oregano, and mixed berry honey from Pacific Northwest Honey Co. to cancel out the dry mouth feel and add complexity.

5h. References

1. nofamass. (2021, March 17). Growing Beneficial Herbs for Bees with Ed and Marian Szymanski [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9_5wHw6l11o

2. Coe, P. (2005). Apitherapy bee gardens: exploring a paradigm for bee-centric healing centers. Journal of the American Apitherapy Society. https://www.biodynamics.com/system/files/pdf/Apitherapy%20Bee%20Gardems%20-%20Priscilla%20Coe%20%28Spring%202006%20No.%20256%29.pdf

3. Wilson-Rich, N. (2014). The bee: a natural history. Sussex, UK: Princeton University Press

4: Wojcik, V. A., Morandin, L. A., Adams, L. D., & Rourke, K. E. (2018). Floral Resource Competition Between Honey Bees and Wild Bees: Is There Clear Evidence and Can We Guide Management and Conservation? Environmental Entomology, 47(4), 822–833. https://doi-org.evergreen.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/ee/nvy077

5: Young, B. Schweitzer, D. Hammerson, G. Sears, N. Ormes, M. Tomaino, A. (2016). Conservation and Management of NORTH AMERICAN LEAFCUTTER BEES. Arlington, VA: Natureserve.

6: Moisset, B. Leaf Cutting Bees (Megachile spp.) United States Department of Agriculture. https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/pollinators/pollinator-of-the-month/megachile_bees.shtml

7: Marchese, M. Flottum, K. (2013). The honey connoisseur: selecting, tasting, and pairing honey, with a guide to more than 30 varietals. New York, NY: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishing.

8: Adamson, N.M. Border, B. Cruz, J.K. Jordan, S.F. Gill, K. Goldenetz-Dollar, J. Heidel-Baker, T. Hopwood, J. Lee-mader, E. May, E. Vaughan, M. (2015). Native bee conservation, pollinator habitat assessment form and guide: farms and agricultural landscapes. The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. https://xerces.org/pollinator-conservation/habitat-assessment-guides

9: Nuzzi, D. (1992). Pocket herbal reference guide. Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press.