4a. Pollinator habitat research

Native bee spotlight: bumble bees!

Distribution

There are about 40 native species of bumble bee (bees in the genus Bombus) in North America. Worldwide, there are 250 species and 15 subgenera. In North America, native species range from the Pacific coast to Colorado. They tend to live in or near boreal forests, cold prairies, coastal plains, and mountain meadows. some species can survive in arctic temperatures (Koch 2012).

Social life

Bumble bees are social, living in small colonies with a single queen. The subgenus Psithyrus are parasitic on other bumble bee colonies, killing the queen and taking over the hive. Between species the size of a colony ranges from 50 to 1000+ (Koch 2012).

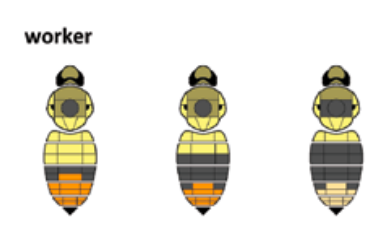

Morphology

Bumble bees have relatively large, furry bodies that allow for activity in cold, cloudy conditions (like the puget sound!). They are corbiculate, meaning they have pollen baskets on their legs. Tongue length ranges among North American bumble bees. Unlike mason bees, they will sting. (Koch 2012)

Bumble bees as agricultural allies

They do produce honey, but not commercially harvestable amounts. They are especially interested in and effective at pollinating crops in the nightshade family, such as tomato (Koch 2012) and other buzz-pollinated plants such as blueberries. According to SARE.org, “tomatoes form larger, more even fruits with buzz pollination” (Mader et al. 2010). They have long tongues compared to honey bee, and can tolerate lower light levels and temperatures. They emerge at 45F making them effective pollinators of crops like raspberry and watermelon which release pollen early in the morning. They are great in greenhouses for a couple of reasons. First, because they seek out the closest suitable forage, whereas honey bees will find a way out of the greenhouse to find better resources. Secondly, it is easy to relocate and situate a bumble bee nest into a greenhouse. (Mader et al. 2010)

Diet

Generalists, they pollinate both self-compatible and outcrossing plants. Collect extra pollen for brood. They need nearly constant forage to sustain a hive, and the abundance of floral resources correlates directly with the density of individuals in a given area. (Koch 2012)

Life cycle

Queens live only 1 year, but can lay as many as 1000 offspring. The queen hibernates alone in a ground cavity until spring. She emerges, foraging along her way as she looks for a nesting site. The queen will lay her eggs after she’s made some cells filled with pollen. She will then sit on these pods like a mama bird. The mature offspring emerge in 4 weeks. These all-female workers will get to work foraging and caring for the queen’s subsequential brood (drones and queens). Fertile drones and queens will mate, the males will die, and the new queens will each establish a new colony after hibernation in the spring. Each species varies in phenology of these events. (Koch 2012)

Nesting

Most bumble bees nest in the ground in existing cavities or burrows. Some nest in wood piles or man-made structures. (Koch 2012)

Some bumble bees species whose range includes the South Salish Sea according to Koch 2012 are:

- Nevada bumble bee (B. nevadensis)

- Obscure bumble bee (B. caliginosus) (endangered)

- Van Dyke bumble bee (B. vandykei) (endangered)

- Sitka bumble bee (B. sitkensis)

- Yellow head bumble bee (B. flavifrons)

- Fuzzy-horned bumble bee (B. mixtus)

- Black tail bumble bee (B. melanopygus)

- Vosnesensky bumble bee (B. vosnesensky)

- Two form bumble bee (B. bifarius)

- Red-belted bumble bee (B. rufocinctus)

- Brown belted bumble bee (B. griseocollis)

- Western bumble bee (B. occidentalis) (endangered)

- White-shouldered bumble bee (B. appositus)

- California bumble bee (B. californicus) (endangered)

- Indiscriminate cuckoo bee (B. insularis)

- Fernald cuckoo bee (B. fernaldae) (endangered)

- Suckley cuckoo bee (B. suckleyi) (endangered)

To pick a bee to highlight in detail, I found the Bombus spp. sighting on iNaturalist closest to the farm, and tried to identify it using this guide. I’m pretty sure it’s B. mixtus.

My notes

Bombus mixtus: the fuzzy-horned bumble bee

Range: Pacific Coast east to CO rockies, north to Alaska, usually high elevation (Koch 2012). Grassy, shrubby open area and mountain meadow (Fretwell 2015).

Morphology: Medium length tongue (Koch 2012). Queens are 15-17 mm and the workers are 10-14 mm (7). Workers have a yellow and black thorax and their abdomen is (in order T1 to T5): yellow, yellow and black, black and maybe a little orange, pale orange, orange (2, 7).

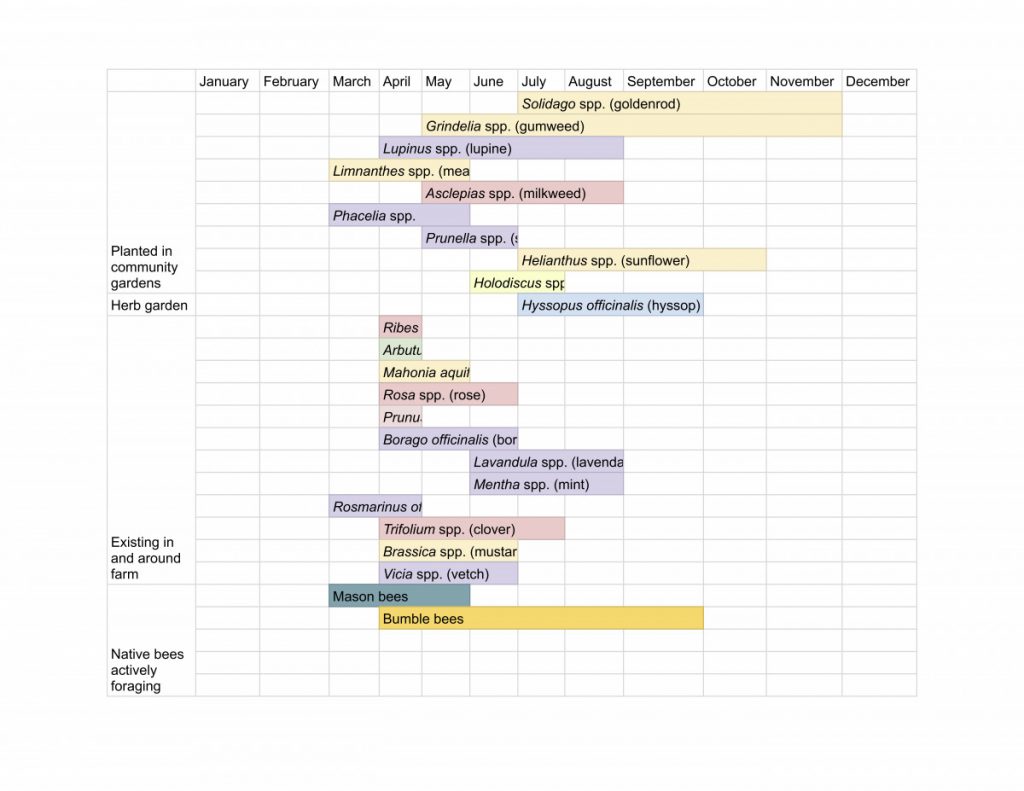

Known forage genera that match up with those that grow at the Organic Farm: Rubus, Trifolium, Lupinus, Epilobium (Koch 2012), Achillea, Phacelia, Solidago, Vaccinium, Astragalus (7), probably more.

Nesting: Near meadow. On, above, or below ground. Queens Sometimes invade nests of the same species. (7)

Relevance to Agriculture: mixtus frequently visits cranberry and blueberry (7).

Phenology: Forage April through July, establish nests in May through June (Koch 2012).

Conservation threats: None. They are common (Koch 2012) and apparently stable in population (Fretwell 2015).

Bombus insularis: the indiscriminate cuckoo bee

Bombus insularis belongs to the subgenus Psithyrus, cuckoo bumble bees, who are parasitic (4).

Range: tundra, taiga, mountains, and maritime regions (4).

Forage: do not have the ability to collect pollen, so rely on other species’ nests. They are short-tongued, and feed on many different flowers for nectar, including the genera Solidago, Vaccinium, and Aster (3).

Nesting: kills the queen of another bumble bee species’ nest and assumes their role (4)

Hosts: B. appositus, B. fervidus, B. flavifrons, B. nevadensis, and B. ternaris (4)

Life cycle: offspring are never workers, because they employ the workers of other species. All Bombus insularis offspring are queens or drones. (3)

Phenology: active May through September (3).

More research: forage

Notes from 100 Plants to Feed the Bees by the Xerces Society

Animals pollinate 90% of plants. Flowers co-evolved with pollinators, resulting in a variety of relationships. Some flowers evolved to promote outcrossing, becoming self-incompatible, putting distance between anther and stigma, having male and female parts be fertile at different times, and even having separate individuals for male parts and female parts.

Plants produce nectar for adult bees and pollen for brood (offspring). Non-parasitic adult bees gather pollen, some in “pollen baskets” (hairs on their legs) and some on other parts of their body. Some pollinators have evolved floral constancy, meaning a specialized relationship between the plant and the animal (think milkweed and monarchs).

Some specialized relationships based on morphology include short tongued bees foraging on sunflowers, and long tongued bees (or strong bees) foraging on tubular gentian.

Reasons for plant-pollinator compatibility include phenology, morphology, color, and odor.

Attraction: how do flowers flirt?

- UV color

- Color phases: using color to signify stages of fertility

- Nectar guides: patterns and colors like a “landing strip” indicating the location of rewards

- Fragrance: communicates over long distances to attract bees

Floral rewards (from a bee’s perspective):

- pollen: protein, aminos, and trace minerals

- nectar: carbs/ sugars

- oil and resin: calories, medicine, and waterproof, antimicrobial building substance

Other useful plant parts:

- Hollow canes (for mason, carpenter, or masked bees)

- Stalks, stems, twigs

- Leaves, petals, fiber

- Peeling bark

The ideal habitat (Lee-Mader 2016)

- 12-20 species at least, 3+ blooming at a time. Diversity is key; more species means a longer flowering season

- 10-30% of farmland

- 5,000+ square feet

- Group similar plants in 4+ sq ft sections

- No insecticides

- Minimum 50-100 ft buffer between pollinator landscape and insecticide-treated crops

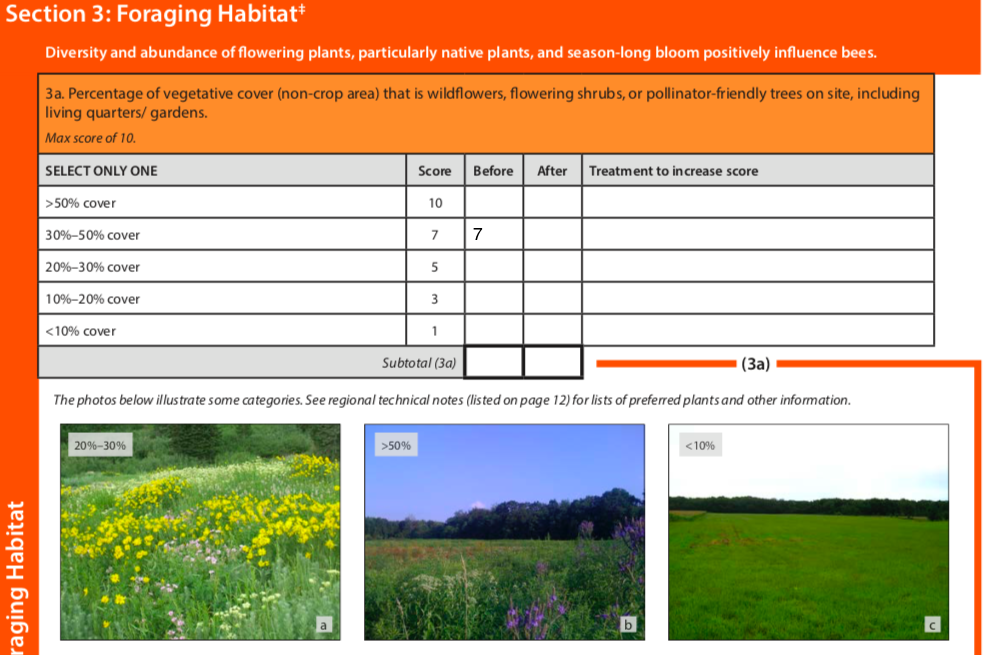

4b. Habitat assessment and improvements

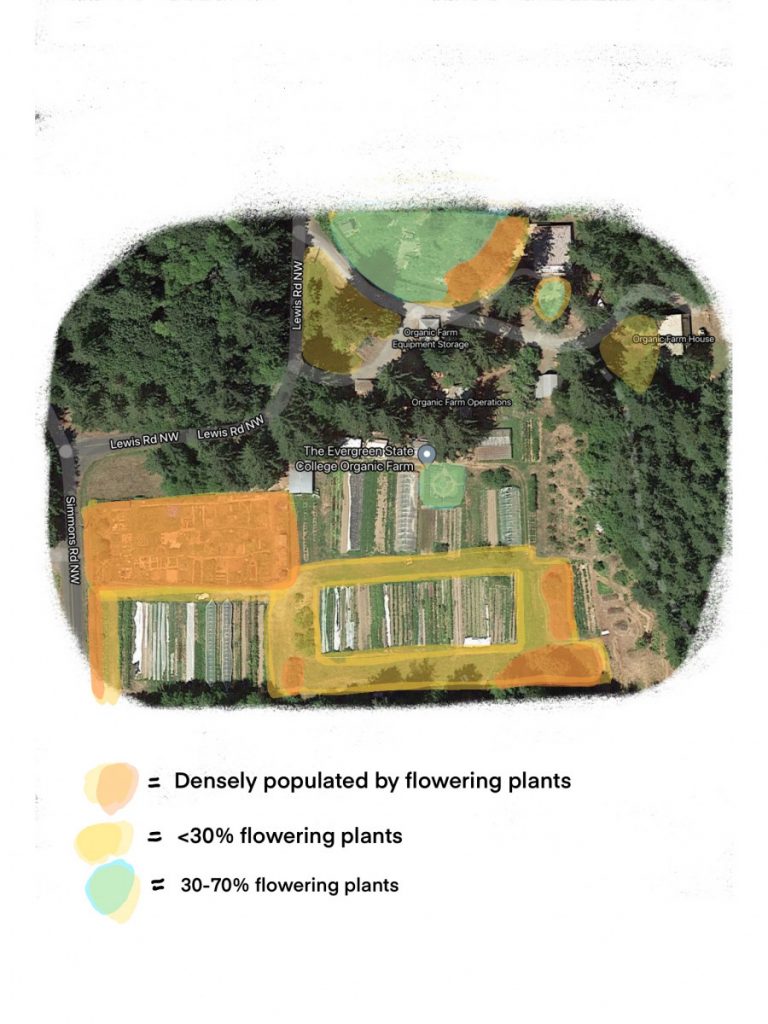

The landscape of the organic farm is unusual. Although there’s not much wildflower meadow space, there is plenty of flowering shrubs in the forest surrounding it. There is also a generous variety of habitat on and around the farm, and new projects in development. Therefore, estimating a percentage of non-crop land that’s populated by wildflowers and other pollinator forage plants is both reductive of the overall forage resources present to pollinators, and difficult to objectively quantify. Even so, within the limits of the farm, I very loosely estimated 30-50% of non-crop cover to be floral resources.

I simplified my notes into this visual map of where wildflowers and flowering trees and shrubs are currently visible. The orange areas are densely populated by flowering plants, mostly native, including the community garden, the trees in demeter’s garden, and some clusters of mini-habitat consisting of mostly native shrubs (bottom of map). The yellow areas are sparsely populated by flowers from what I can tell. Those areas are mostly grassy. The blue-green areas are a mix of grass and flowers.

Gardening for the bees

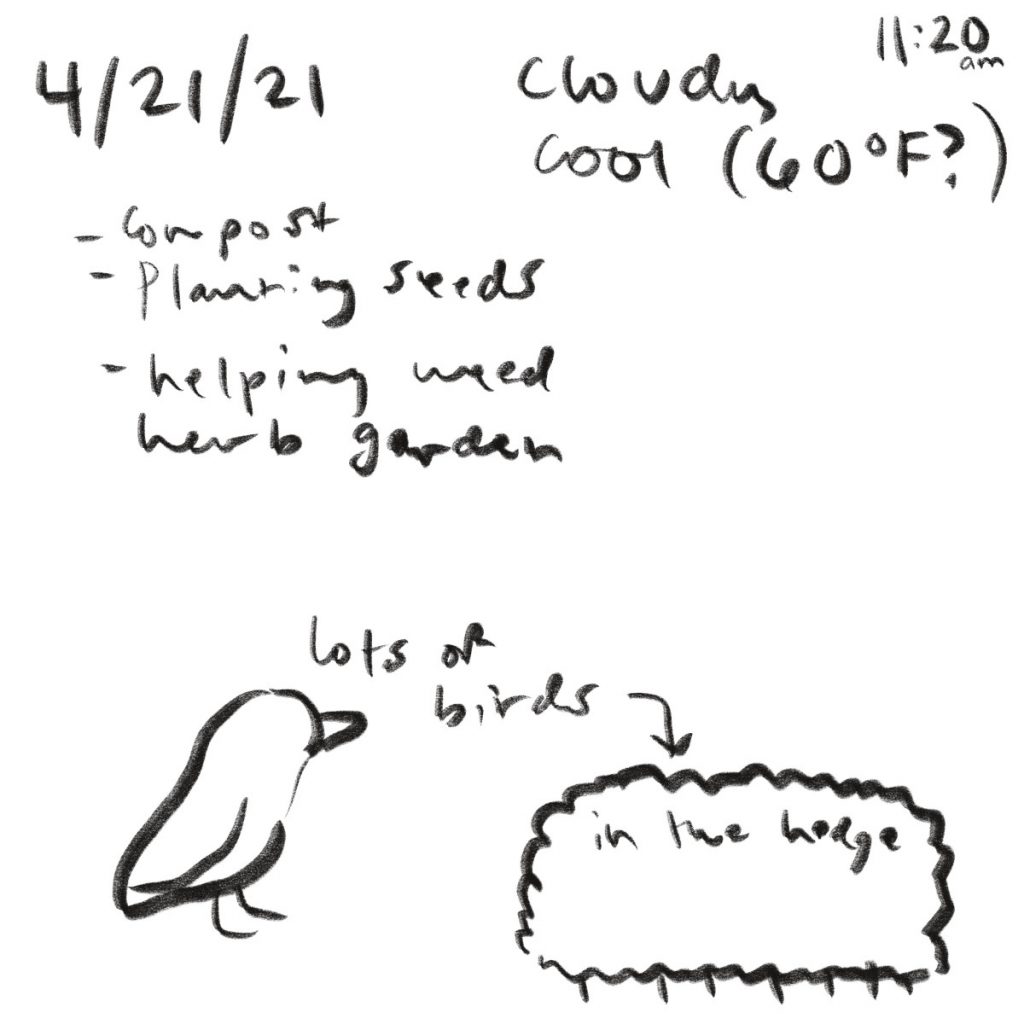

On Tuesday I weeded two small, sunny areas in an abandoned community garden plot to sow some wildflower seeds. On Thursday, I mixed in compost and planted phacelia (Phacelia tanacetifolia) and a native pollinator seed mix from Northwest Meadowscapes. I also spent the last hour in the herb garden weeding with Alegra and Le’Allen to rescue some perennial herbs that were being choked by buttercup.

The native pollinator mix I bought from Northwest Meadowscapes includes the following plants:

Annual forage

- Douglas meadowfoam

- Collomia

- globe gilia

- farewell to spring, winecup, and diamond clarkia

- sea blush

- Clover

- popcorn flower

- Lupine

- Menzie’s fiddleneck

Perennial forage

- Self-heal

- Yarrow

- Common and large camas

- Gumweed, big leaf, and river bank lupine

- Goldenrod

- Checkermallow

- Milkweed

- Sunflower

- Fleabane

- Horsemint

- Barestem biscuitroot

- Cinquefoil

- Spring gold

Grasses

- Roemer’s fescue

- Tufted hairgrass

- Meadow barley

4c. Film/media analysis and tasting research

After watching Queen of the Sun last week and noticing the lack of women’s voices in that piece of media, I decided to seek out a feminine perspective explicitly. After searching around I came across this article by Ariella Daly. Instead of watching a film this week, I listened to the hour long episode #097 of Dirt in Your Skirt with Margaret Schlachter. I enjoyed her very spiritual take on beekeeping.

Daly says that history is written in men’s voices, while folklore is told by women. She talks a lot about bees in folklore, spirituality, and archetypes. The Mellisae were priestesses in ancient greece, named after bees. Honey and milk are both feminine in nature, products of reproductive labor performed by the female of each species. St. Brigid in Irish-pagan mythology travelled with bees as her handmaidens to protect her with their stings while she brought the plants to life in the spring. She’s like a queen bee.

The way she views the society in a hive is that the workers and the queen sacrifice for each other. The queen does not rule over the hive. Drones, workers, and the queen work together to build a home and reproduce.

Ariella Daly, “I started beekeeping over a decade ago for a number reasons. Sure, I wanted to save the bees like the rest of us, but my motives were much less altruistic than that phrase entails. I wanted to mother something. I had just suffered a traumatic miscarriage, and I needed to take care of something precious and full of life.”

Daly says that a hive came into her life shortly after she miscarried. At minute 22:00 she shares this story, saying that she was “spiritually bleeding out” and that beekeeping saved her. She goes on to discuss how tending a hive, honey, and even being stung can all be medicine.

Beekeeping as therapy: minutes 29:00-32:30

Tending a hive requires you to be very present and calm. The host, Margaret Schlachter, shares from her own experience, “if you’re having a crappy day, and you bring that energy to the beehive, they know.” Daly agrees, saying “bees are a bridge species between the wild, our wild nature, and…our domesticated lives… What we bring is reflected immediately back to us.” This reminds me of working with horses. It’s scary at times, and requires attentiveness. The animal picks up on any slight body language that you’re nervous, and almost always reflects that back at you. You have to earn their trust and stay very calm and confident.

“There is so much healing that can happen through working with bees. A lot of people get into working with bees because they need nature connection, or they need to calm the F down” (Daly laughs). She notes that beekeeping can be incredibly healing for veterans with PTSD, incarcerated folks, and women. She says that working with the “womb”, the hive, brings up a lot of trauma for women and an opportunity for therapy in that sense.

If you’re interested in hearing more, in this video she discusses the parallels between control of a woman’s reproductive power and control of the honey bee, among other topics.

On another personal note, listening to Ariella and the Margaret was very healing. Many media resources I find are from the perspective of men, and just listening to a person orate in a feminine way, and be heard and respected, was something I didn’t know I was missing.

Next week I want to dive more into how bee products, bee husbandry, and bee gardening can all be healing, inspired by this Ariella’s work. What is the intersection between holistic medicine and bees? I hope to tie in my work in the herb garden.

4e. Sensory analysis

This week I went off book a little because I really wanted to taste for myself whether the flavor of honey varietals reflects the plant who’s nectar it’s derived from. I didn’t have access to the appropriate flowers, so I gathered what I could: dried red clover leaves for “wildflower” honey, dried alfalfa leaves, frozen blackberries, and carrot root. To try this at home, you’ll need:

- A few kinds of honey with the forage plants identified (“clover honey” for example)

- Some plant matter from the kind of plant the honey bees foraged from

- Hot water

- Several roughly equal-sized heat safe cups

- Measuring spoons

- Pen and paper

Methodology: I then steeped 1 tablespoon of each plant and one teaspoon of each honey varietal in roughly 100 mL of hot water. I had my trusty lab aid (my live-in partner) steep the honey, and I labeled each cup with a symbol so he could tell me which was which after I’d done the experiment. Next, I did my best (using tasting advice from The Honey Connoisseur) to match the plants with the honey.

Results: I was way off. The only honey I successfully matched with its plant of origin was blackberry.

Conclusion: if I was to apply this casual experiment to form an opinion about the terroir of honey, I’d have to say that honeys taste much different than the plants they come from. I would love to try this experiment again with the flowers from each plant instead, because so much of flavor is aroma, and sometimes the flowers of a plant smell much different than their other parts.

I also did the exercise in Chapter 5: Tasting Honey of The Honey Connoisseur, under the section titled “Flavor”. Similarly to the jelly bean experiment from Taste by Barb Stuckey, the exercise had me experience the honey with my nose pinched versus with olfaction in play. I was not surprised to find that a product derived from flowers was missing most of its allure without aroma, but I was surprised to find that all the honeys were noticeably salty. I am curious whether this is a reflection of the coastal climate.

4f. Special events

This week I attended Farmworker Justice Day and was so glad I did. The guests included folks from Familias Unidas por La Justicia and from Community to Community.

FUJ is a union of 400+ indigenous Mixteco and Triqui farm workers. They led strikes and boycotts against Driscoll for 4 years before being recognized. They even started a worker-owned berry coop, Tierra y Libertad.

C2C calls itself a “place-based”, “eco-feminist” organization. They are woman-led out of Bellingham, established in 1980.

At the webinar, they mostly shared the experience of farmworkers during COVID. After a year of constantly fighting for PPE and paid sick leave, with little success, their current project is getting workers access to vaccinations. Workers not only are facing the barriers of language and time that they leave work, but also justified lack of trust in medical providers, especially for women.

As I listened I noticed a possible parallel between farmworkers and pollinators. They migrate for work, are taken for granted despite being recognized as “essential”, first affected by the repercussions of capitalism, and are incredibly powerful when organized.

4g. Cooking/foodoir writing

4h. References

- Lee-Mader, E. Fowler, J. Vento, J. Hopwood, J. (2016). 100 plants to feed the bees: provide a healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing

- Koch, J. Strange, J. Williams, P. (2012). Bumble bees of the western United States. Logan, UT: Pollinator Partnership. Link

- Bombus insularis: indiscriminate cuckoo bumble bee. Bumble bee brigade. https://wiatri.net/inventory/bbb/resources/SpeciesDetail.cfm?ESTID=11416

- Bombus insularis. (2021, February 27). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombus_insularis

- Inaturalist listing by Luca_hickey

- Fretwell, K. Fuzzy-horned bumble bee, orange-belted bumble bee, mixed bumble bee: Bombus mixtus. (2015). Biodiversity of the Central Coast. https://www.centralcoastbiodiversity.org/fuzzy-horned-bumble-bee-bull-bombus-mixtus.html

- Fuzzy-horned Bumble Bee: Bombus mixtus. (May 4, 2021) Montana Field Guide. Montana Natural Heritage Program. http://FieldGuide.mt.gov/speciesDetail.aspx?elcode=IIHYM24160

- Mader, E. Spivak, M. Evans, E (2010). Managing Alternative Pollinators. 43-53. SARE Outreach. Link

- Schlachter, M. (Host). (2016-present). Dirt in your skirt [Audio podcast]. Episode 097. https://dirtinyourskirt.com

- Marchese, M. Flottum, K. (2013). The honey connoisseur: selecting, tasting, and pairing honey, with a guide to more than 30 varietals. New York, NY: Black Dog and Leventhal Publishing.