To gain an understanding of Italian food as we know it, one must first examine its origins. The spaghettis and pizzas of today would be entirely foreign to an Italian of 100 years ago, so changed is Italian culture and cuisine. Italian food as a concept is even still a relatively new idea, finding its basis in the Risorgimento or Italian unification of 1861 which lead to the creation of the Italian state (Risorgimento, Encyclopedia Britannica).

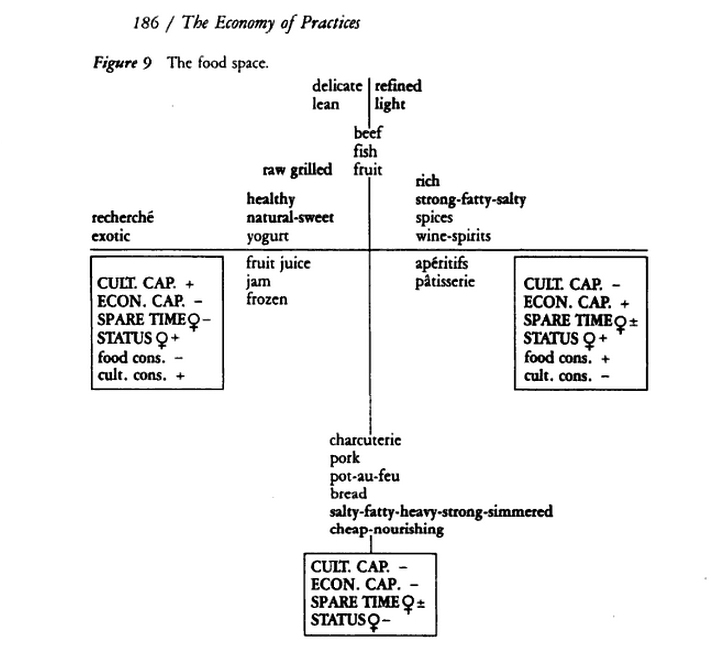

At this time, Italian cuisine could be divided into two categories: the hedonistic and over the top tastes of the upper and middle class, and the meager peasant food of the lower class. Upper class Italians favored French flavors of the day, not only enjoying French haute cuisine whenever they could, but also employing the French language whenever they could. The lower class would find themselves eating nutrient-light heavy meals made up of simple dishes (Lo Weis, Tasting Fascism: Food, Space, and Identity in Italy). This great disparity between the two conjures up Pierre Bordieu’s theory on the “taste of luxury”, the upper classes favoring and enjoying “delicate” and “refined” dishes while the lower class subsist on a paltry diet of “salty-fatty-heavy” foods.

Lower class diets were made up of pasta, cornmeal, and bread alongside legumes, fresh produce, and the occasional meat. Sweets, liquor, and coffee were rare occurrences. Food was there to fill ones belly, and was by no means consumed for pleasure. In opposition to this was the upper class, who ate only for pleasure, for whom food was more about showing off ones status than anything else. The more French the food you ate and the language you used to describe it, they higher your status appeared to be. To the Italian elite, French cuisine became synonymous with luxury and class (Lo Weis, Tasting Fascism: Food, Space, and Identity in Italy).

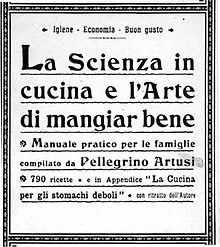

This push into French cuisine and culture, reaching its peak in the nineteenth century, was met with a drive towards Italian culinary nationalism. One man who had a major influence on this movement was Pellegrino Artusi. His book, La scienza in cucina e l’arte di mangiar bene (The science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well), subtitled Manuale pratico per le famiglie (Practical Manual for Families), published 1891, was instrumental in the shift from French to Italian food by the upper and middle classes. This cookbook being released shortly after the Italian unification came at a time when many people were rethinking Italian identity and their personal relationship to it.

This book was unique in many ways, not only was it written for, by, and in Italian, it also highlighted Italy’s culinary diversity and pushed for its celebration rather than suppression. Essentially a compilation of regional dishes around Italy, Artusi promoted Italian nationalism by creating a cohesive Italian cuisine found though common tastes throughout Italy. One example of his efforts towards this was the flexible instructions found in La scienza in cucina. Herbs were often not specified, rather prompting the cook to use what they had regionally. Spices were also added to taste, his ambiguous directions giving the reader space to appropriate the dish to their tastes and region. This showed Italians that any dish throughout Italy could be feasibly made, no matter ones location. His exilation of both French language and flavors from kitchens prompted cooks to find substance and inspiration within their own country’s borders (Lo Weis, Tasting Fascism: Food, Space, and Identity in Italy).

While his work was not explicit nationalist propaganda, his book did create a sense of unification throughout Italy as well as a push towards national pride. Suddenly, both the rich and poor were both eating Italian food, and while the amount and quality of the food both groups consumed were still greatly different, the flavors were the same. There was one less barrier between the two. This relative closeness fostered a sense of oneness throughout the nation, setting the stage for impending fascism that wold sweep Italy.

As Mussolini would later discover, the way to the minds of the Italian people was through the kitchen; if you alter national dogma towards food, everything follows. Artui’s work was an early example of this, his book not only changing culinary tastes throughout Italy, but also the way Italians felt about their own nationality. La scienza in cucina was the foundational building block of both the Italy and the Italian food we know today, showing Italian cooks that they need not look any further than their own doorstep for good food.

Be First to Comment