The onset of fascism in Italy greatly shifted both agricultural and culinary practices throughout the country. Pasta, an age old staple in Italian diets, especially in the south took the biggest hit from Futurists and Fascists alike, seeking to change the diets and minds of their citizens. This core carbohydrate, made of flour and eggs would be criticized and shunned off dinner tables. In its place, rice was suggested to fill Italian bellies.

In the age of Fascism, grain was a hotly contested subject. Wanting most, if not all, food products to be sourced directly from Italy, Mussolini cautioned Italians to be conservative with their wheat usage. Italian grain production was a main focus of the regime, wanting to increase grain production while also not relying on imported flour or other grain products. He wanted Italy to be self sufficient, providing all of its needs from within its borders.While wheat production was not necessarily meager, the amounts of pasta and bread being served on Italian tables was more than internal grain production could keep up with (“Mussolini, Oppressor of Pasta”, David McKenzie, Contemporary Food Lab).

Mussolini saw three solutions to this problem as listed by David McKenzie in his article “Mussolini, Oppressor of Pasta”:

1) Stop eating wheat, or eat less.

2) Produce more wheat.

3) Eat less of everything. (McKenzie)

Trying his hand at the first solution, Mussolini pushed Italians to eat more rice and vegetables, two bountiful products of Italian agriculture. Alongside Mussolini’s efforts were those of the Futurists. This artistic and social movement swept Italy in the years before World War Two. It focused on industrialization and technology, pushing Italy towards a dynamic future. Futurist ideology teamed up with Fascists on many occasions, the issue of wheat being one of them. They felt as though pasta was the food of a lazy and apathetic people, not one of a changing powerful nation of healthy and strong youth. Futurists were staunchly anti-pasta, describing it as “a form of slavery…. It puffs up our cheeks like grotesque masks on a fountain … it nails us to the chair, gorged and stupefied, apoplectic and gasping” (Carol Helstovsky, Garlic and Oil: Food and Politics in Italy, Berg, Oxford, 2004 at 78-9). This campaign raised peoples awareness of the food that they put onto their tables and into their mouths, whether or not is affected the amount of pasta being eaten.

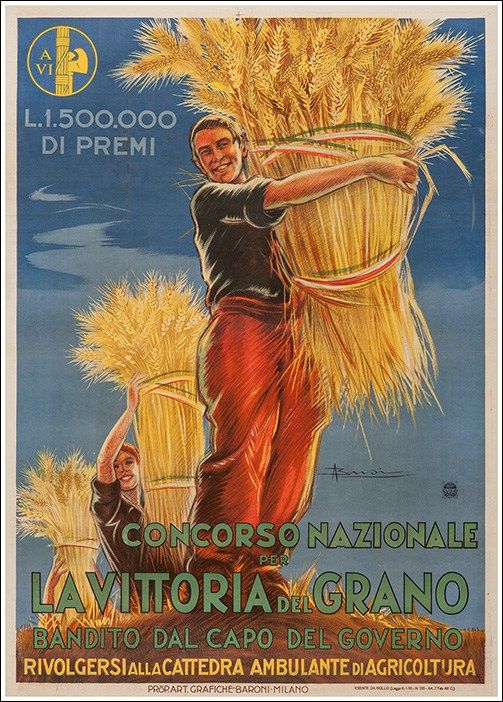

The second solution would take more than a spaghetti smear campaign. Farmland previously used to grow other foods was taken over by wheat farming. Subsidies and incentives were offered to farmers willing to grow wheat. Each year farmers would compete to win the Vittoria del grano (victory of grain), where monetary rewards would be given to the farmers who produced the most bushels of wheat. Propaganda showed women and men smiling in fields shouldering large bundles of grain, no sign of hard work on their brows. Other posters showed young children planting seeds in awaiting Italian soil, farming shoulder to shoulder with their peers in the filed. Other propaganda being circulated at the time was that of Mussolini himself farming. Shirtless, helping bundle wheat, he was the perfect example of an Italian enthusiastically putting in the work for his nation. Other pictures showed him threshing wheat alongside a peasant woman. Agricultural work was highly encouraged, to the point of Italy’s own Fascist leader shouldering the burden, if not just for a photo op (Lo Weis, Tasting Fascism: Food, Space, and Identity in Italy). While there was more wheat being produced, the prices were higher than ever. Heavy tariffs on wheat on top of rising prices in food markets meant that few Italians could afford wheat products.

High prices on wheat combined with unchanging wages meant that Italians were eating less pasta than they were, whether or not that was the result of successful propaganda or not, meaning that the third solution o the list, “eat less of everything” proved to be the most successful (“Mussolini, Oppressor of Pasta”, David McKenzie, Contemporary Food Lab).

In the years following Mussolini’s death, pasta reemerged as a staple on Italian tables. Italy’s industrial boom made pasta production easier and cheaper, and that paired with flour imports meant that Italians could afford to eat pasta again without propaganda urging them against it.

Homemade Pasta

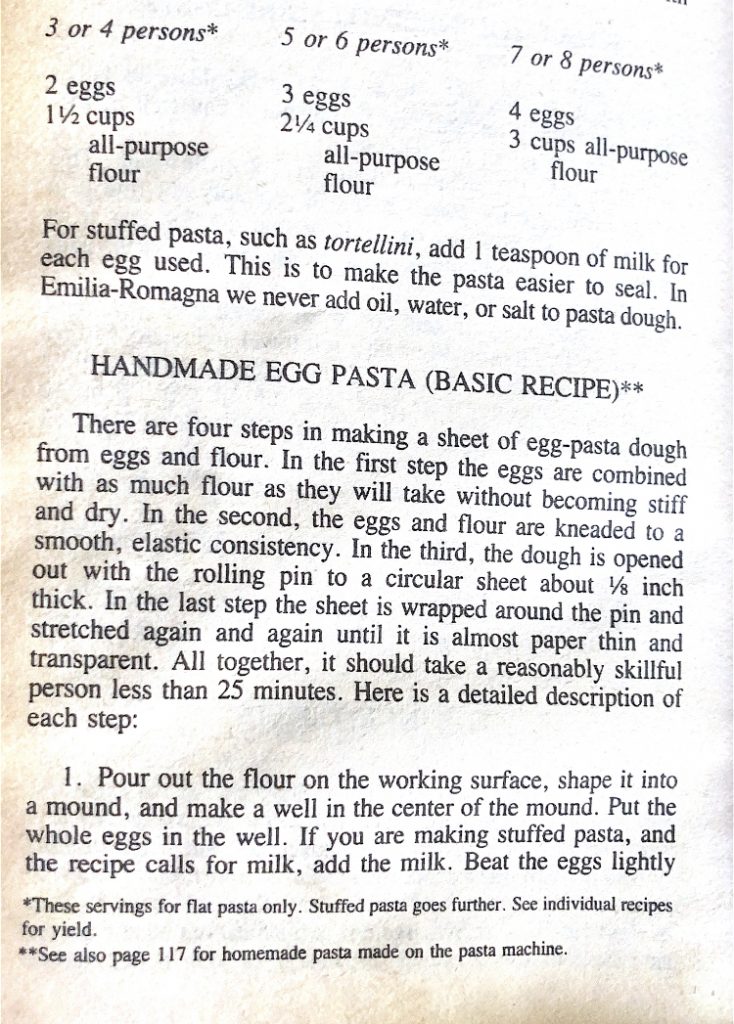

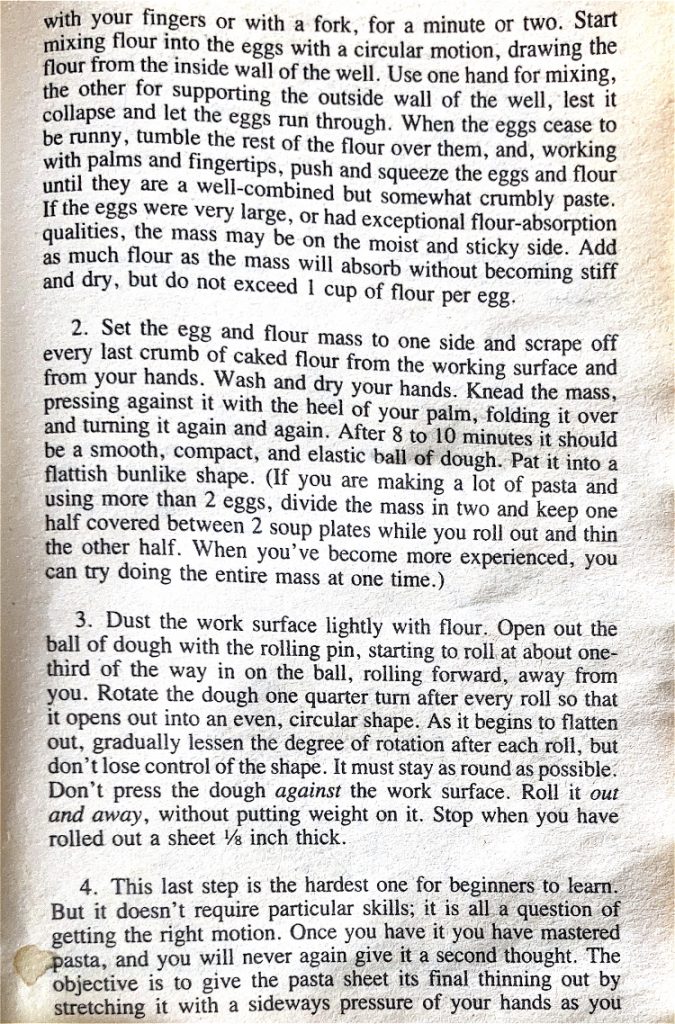

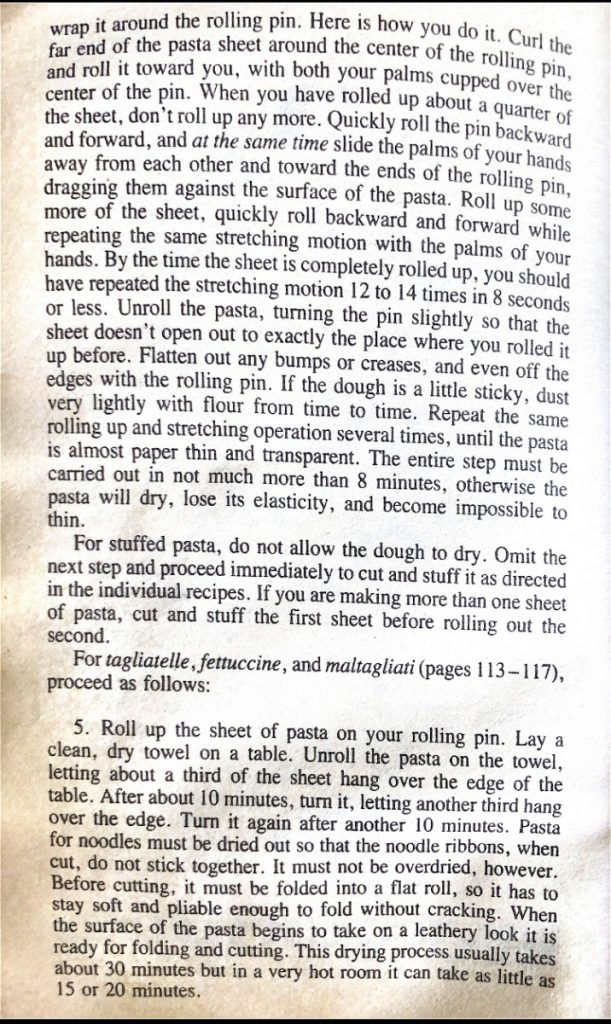

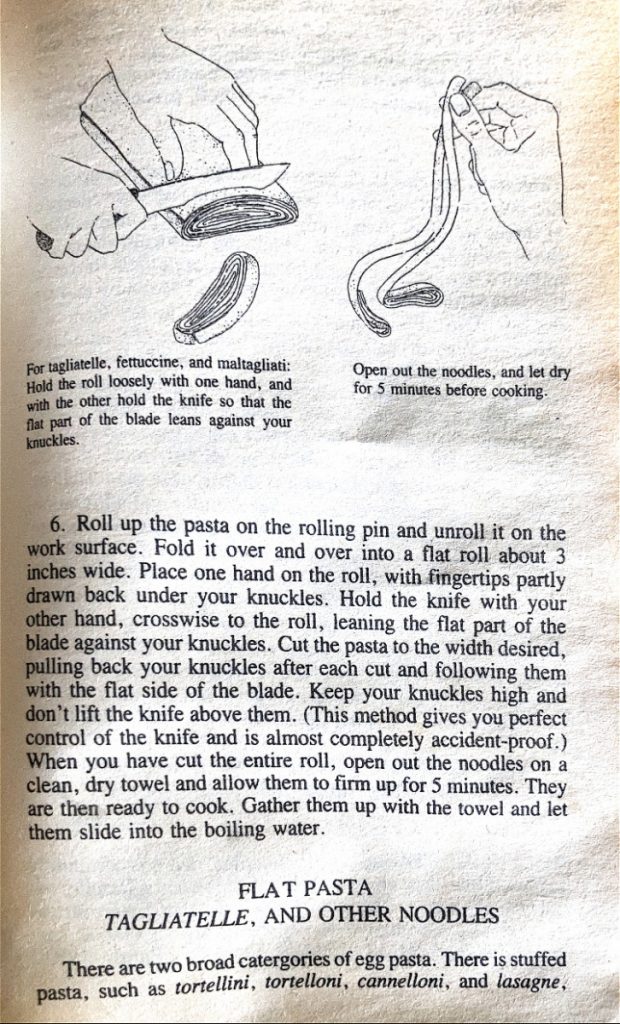

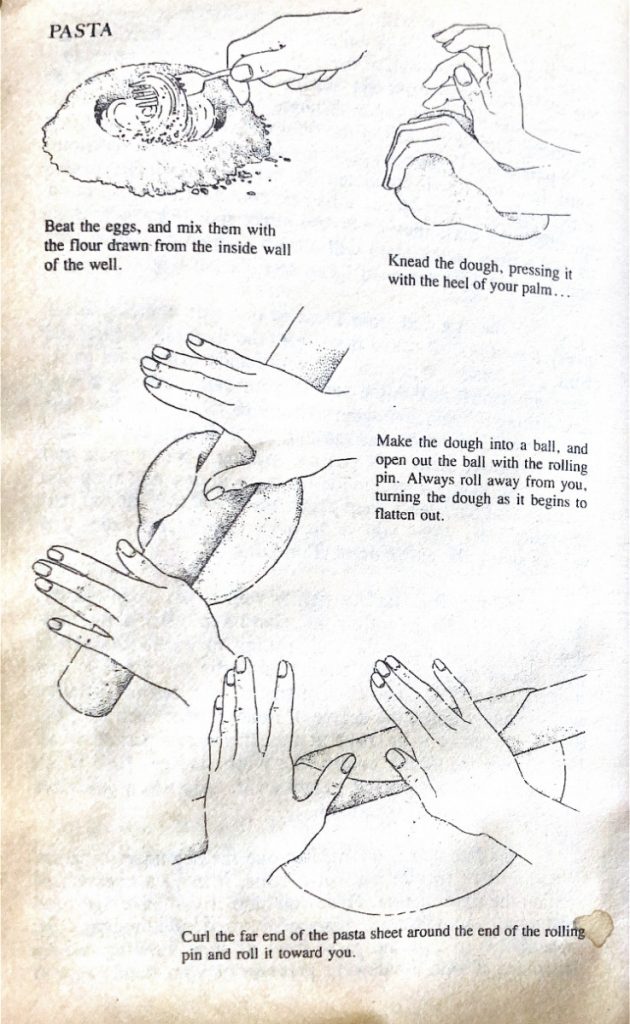

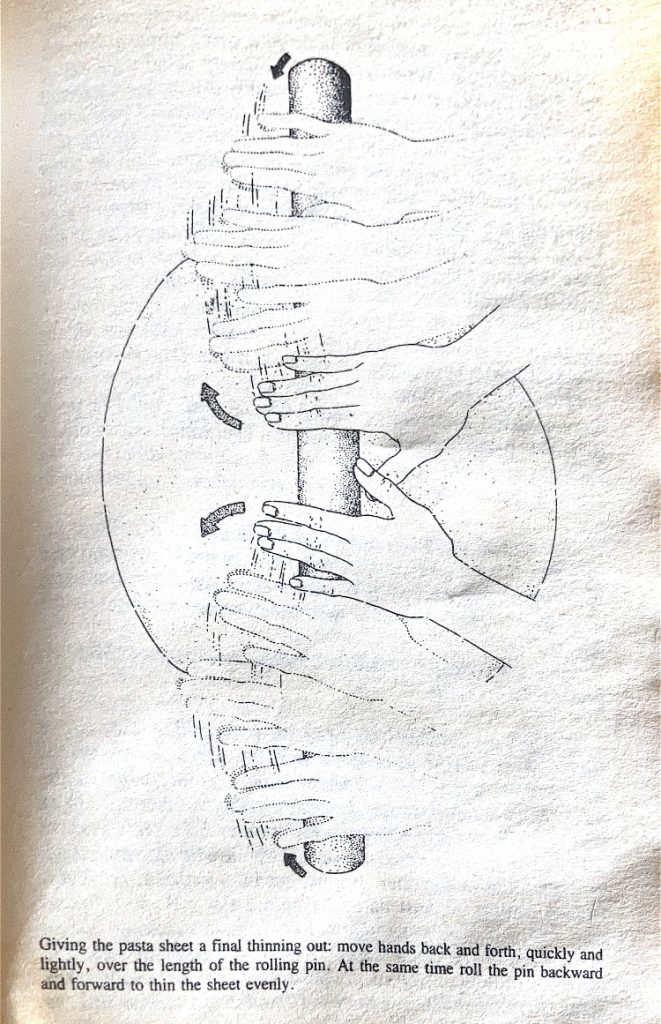

Recipe from The Classic Italian Cookbook, Marcella Haszan 1973

(Sorry I didn’t write out all the instructions, that is way more text than I am willing to transcribe!)

Notes:

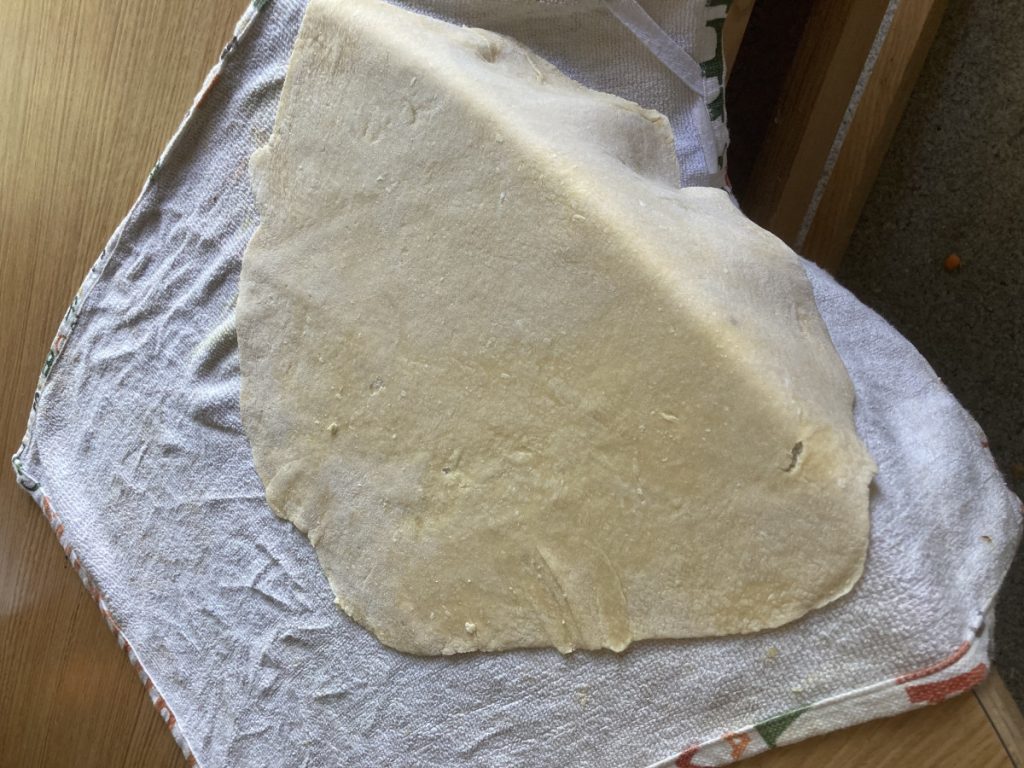

I would air on the side of too wet more than dry with this recipe. I tried this out a couple times and my dough always dried out before I could roll it thin enough. It should be a little sticky as you knead it, add flour if you need to during this step to form the right consistency.

Afterthoughts

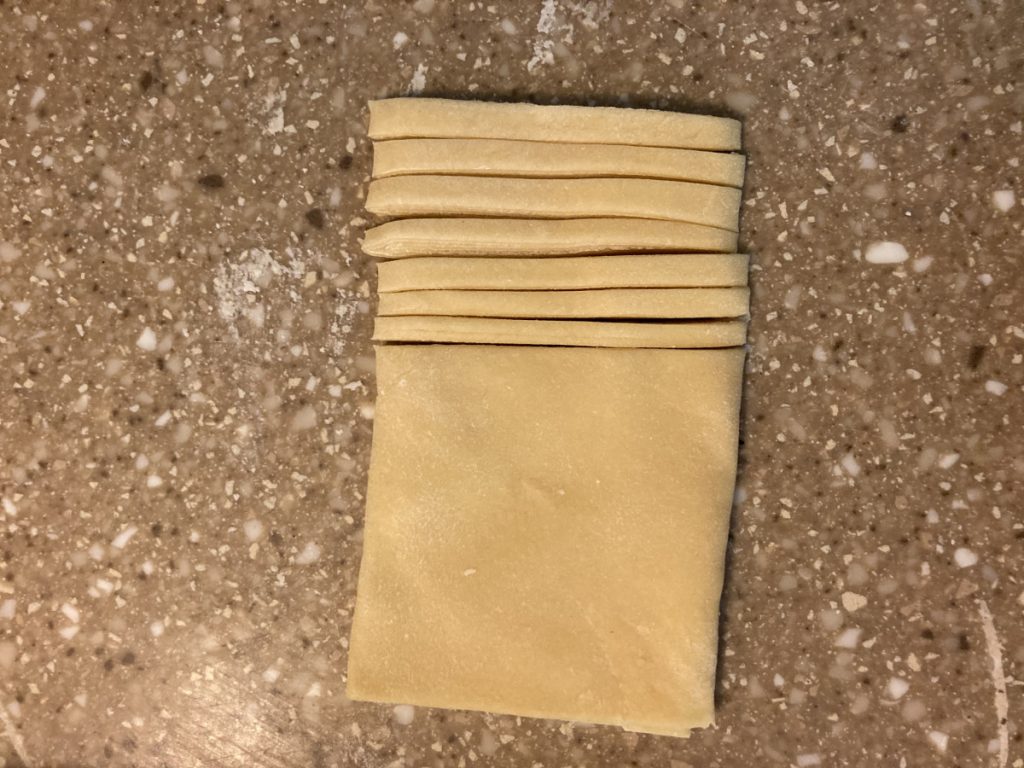

I had a hard time with this pasta. I have made homemade pasta before and thought that this experience would be a breeze. Instead, I found myself on my third try before getting it right. As I said before, the dough gets dry really fast and because it spends no time in the fridge, you have to work quickly if you want it to be able to get it thin enough.

I think the reason I had such a hard time with this particular recipe is because it is all based on intuition. The measurements given are just a starting place, the amount of flour listed is more than enough and should be used sparingly. The instructions for rolling out the dough are very vague but there is also a lot of stress put on the importance of rolling it the correct way. It became clear to me that this recipe and method would be the easiest thing in the world if I was raised making it. In essence, Hazan is trying to prompt the cook to make the confident intuition based decisions that a life long pasta maker would.

As for the taste, this is one of the best I have ever made. The texture is perfect, the rolling technique makes for just the right thickness. The tase is subtle and the perfect support for whatever topping you decide to put on it. Even though the changes are slight between this recipe and others I have made, it really does make a difference.

Be First to Comment