Parasites and Feeding Strategies

Feeding Strategies: Hunter or Gatherer?

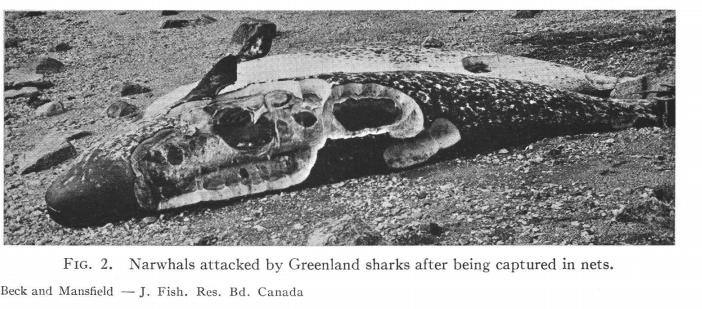

As the speed of ectothermic animals is often dependent on the ambient temperature around them, seabirds and mammals generally have trophic superiority over ectothermic fish in cold regions. This is in contrast to warm water environments, where sharks are able to swim faster and take down endothermic prey. Despite this, the Greenland Shark is rather unique in its ability to hunt mammals (particularly seals) as a cold-water ectotherm (Watanabe et al 2012). In addition to several species of seal, Somniosus microcephalus feeds on mollusks, echinoderms, crustaceans, polychaetes, and many different species of fish, including those of their own species. ( Leclerc et al. 2012)

Surprisingly, despite what observations of burst swimming and their ability to collect warm-blooded prey might suggest, the Greenland Shark is still the slowest moving fish studied as of 2012. With a top recorded mean speed of 0.74 m·s−1 vs a top mean speed of 1.7 m·s−1 for pinnipeds, it is unlikely that S.microcephalus actively hunts seals. The Greenland Shark is also thought to have poor sight due to a common copepod parasite that attaches itself to the shark’s eyes, Ommatokoia elongata (Devine et al 2018). Due to these factors, it’s been suggested that they act as scavengers, or even prey on seals while they are sleeping. (Watanabe et al 2012).

Multiple feeding strategies have been proposed from analyzing food found in the sharks gastrointestinal tracts. One of these strategies is suction feeding, supported by the lack of bite marks on smaller pieces of ingested food. Bites taken from large pieces of food show a characteristic ‘bowl’ shape.

Worse than an Eyelash: Ommatokoita elongata

Like many sharks in the Arctic, many Greenland Sharks are rendered blind or visually impaired by the parasitic copepod Ommatokoita elongata. Approximately 99% of individuals are afflicted with Ommatokoita elongata, where at least one eye is effected.

In order to attach to the shark, females insert a sort of anchor (called the bulla) into the shark’s cornea. From there the parasite hangs freely and feeds on the eye tissue. Occasionally Sharks can be infected not only in both eyes at once, but can have multiple parasites in a single eye at a time (MacNiel et al 2012).

Recent Comments