Header image is a U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service aerial photo of the Prairie Potholes region, which stretches from Iowa to Alberta and is breeding ground for more than 50% of North American waterfowl.

The Farm Bill is one of those subjects to which, once you start pulling a string, you find the whole world attached. That’s because the Farm Bill sets the rules of the game, influencing not only what we eat, but also who grows it, under what conditions, and to some extent, how much it costs. The agribusinesses and lobbyists that have essentially written those rules for our legislators in recent decades deserve the lion’s share of the responsibility for creating the tangle of problems in our food system.

The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide, pg. 199

The good news is that many of the ideas needed to turn the tables and create a healthy food and farming system largely already exist.

My final book for this quarter is a relatively short one, but as I found with each previous reading, it’s dense with information. I would say that The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide by Daniel Imhoff and Christina Badaracco is the most reader-friendly for a general audience other than Farm and Other F Words, and perhaps the one I’d recommend most highly to understand the guidelines, funding, and policies that concretely shape the U.S. agricultural and food systems. Some chapters contain more concentrated policy analysis than others (Chapter 13, “Trade”, was notably difficult for me to wade through), but overall, this book (3rd edition) is a fantastic introduction to one of the most important and gargantuan pieces of federal legislation in the U.S.

So, what is the Farm Bill? It’s an omnibus bill (simultaneously addresses many different issues) passed every five to seven years with three primary focuses: 1) food nutrition programs, 2) income and price supports for commodity crops and other forms of crop insurance, and 3) conservation incentives. It was originally enacted as a temporary measure to provide relief during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, but has evolved into one of the most significant driving factors of land use in the U.S by directing farming and food policy. Although each Farm Bill has a unique name – the most current bill is formally called the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018, although the Imhoff book only covers up to the Agricultural Act of 2014 – all Farm Bills are divided into spending categories called “titles”.

- Title 1: Commodities

- Title 2: Conservation

- Title 3: Trade

- Title 4: Nutrition

- Title 5: Credit

- Title 6: Rural Development

- Title 7: Research, Extension, and Related Matters

- Title 8: Forestry

- Title 9: Energy

- Title 10: Horticulture

- Title 11: Crop Insurance

- Title 12: Miscellaneous

Although each bill authorization (the first phase) by the Senate and House Agriculture Committees determines how taxpayer funds will be allocated, programs with “discretionary funding” have their fates determined during the yearly appropriations phase, where Farm Bill funding priorities are re-evaluated and budgets are revised. Generally, commodity price supports are the only untouchable spending categories in the appropriations process, and often, commodity growers are actually able to lobby for more money through supplemental disaster payments. Programs that broadly serve the public good, including conservation incentives, organic agriculture research funds, renewable energy programs, food assistance, and beginning farmer supports, tend to be the first to have budgets slashed in appropriations. Even mandatory allocated dollars for these programs are at risk under the Changes in Mandatory Program Spending (ChIMPS) process. As if these funding battles weren’t enough, Congress can also demand budget reconciliation in response to a projected deficit, forcing committees to further decrease spending.

As mentioned above, the first Farm Bill was a response to crises in the Great Depression and a cornerstone of FDR’s New Deal agenda. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 is when the first soil and water conservation districts were founded, mostly at the county level, to demonstrate and promote agricultural practices like tillage, cover cropping, and crop rotation for addressing erosion. One of the primary programs enacted by the first Farm Bill was government purchase and stockpiling of surplus commodities (“basic farm products” = wheat, cotton, tobacco, rice, hogs, and milk) during good production years to raise market prices for farmers by contracting supply, and distribute these goods during times of need. This concept was called the “Ever-Normal Granary” by Henry Wallace, secretary of agriculture. It is interesting to note that this earliest set of commodity programs was in part designed to protect small farmers from corporate agribusiness domination. To participate in government subsidy programs, farmers were required to sign contracts agreeing to production control and conservation programs, and also were offered land-use incentives, credit, and crop insurance programs. Hunger relief and school lunch programs were enacted, and funding was set aside for research into plant and animal diseases and new agronomic varieties.

Although every government dollar spent on these extraordinary New Deal reforms generated seven more in the overall economy, many farmers viewed the legislation as shamefully un-American and a threat to free markets. Rather than being paid to reduce the number of acres cultivated or the amount of livestock raised, some farmers chose to meet the subsidy guidelines by plowing under millions of acres of already planted crops, slaughtering millions of young hogs and dumping them into the Missouri River, and pouring millions of gallons of milk out into the streets, rather than selling these products to the government for aiding the hungry. The replacement of food distribution programs using the term “relief” with the Surplus Commodities Corporation appeased powerful farmer coalitions enough to allow surplus commodity distribution, cotton, wheat, and corn prices doubled within three years, and in 1936, the U.S. Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the Agricultural Adjustment programs that limited acreage and set prices.

This legislation also was the virtual end of sharecropping – as subsidies went to landlords, the owners often bought better machinery and reduced their need for farm labor. As the “Green Revolution” of the 1950s-1970s increasingly mechanized and industrialized agricultural production, overproduction increased, leading the emergency price supports of early Farm Bills to gradually become institutionalized. Perhaps the most radical holistic shift in government agricultural policy since the initial 1933 legislation occured in the 1970s under USDA secretary Earl Butz. In response to a 1972 “secret Soviet grain deal” which drove up domestic wheat prices and foreign demand, he decided that America would feed the world. He egged on farmers to “get big or get out”, “adapt or die”, and “farm fencerow to fencerow” with progress measured only in increasing yields at the expense of the environment, public health, or overall economy. Butz introduced defiency payments to boost income, largely emptied America’s strategic grain reserves, and helped usher in the rise of CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations). Riparian buffers, windbreaks, contour terraces, wildland strips, wetlands, and forests were obliterated to maximize production. By the end of his career, Butz also managed to be convicted of tax evasion and earn a reputation for racial and religious insults. By the early 1980s, corporate agribusiness giants were essentially writing Farm Bills for their own benefit.

At the same time as the consolidation, borrowing, and speculation craze of the Butz era, a sustainable agriculture movement arose in the U.S., but struggled to take hold and become self-sustaining as they were not funded by Farm Bill programs and lacked economic safety nets. Despite this uphill battle, organic agriculture managed to persist and grow throughout the decades, becoming a larger market and gaining widespread appeal by the end of the 20th century. And in response to farmers draining wetlands to expand operations, particularly in the Prairie Potholes Region of the Upper Midwest, the Food Security Act of 1985 (often referred to as the Environmental Farm Bill) set aside funds to enroll about 10% of total U.S. farmed acreage in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). This program also came with disincentives called “Swampbuster” and “Sodbuster”, which immediately withdrew federal payments from farmers who drained wetlands or plowed protected grasslands. The Environmental Farm Bill also introduced the National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service.

The “Conservation Era” continued as each successive Farm Bill added conservation programs too numerous and wieldy with acronyms to handily list here. The conservation programs can be broadly divided into the major branches of the USDA, the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Farm Service Agency (FSA), which administer set-aside and easement programs, habitat-building programs, compliance-oriented programs, and stewardship-oriented initiatives.

A major problem with compliance-oriented programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) is ironically that the worst polluters receive the largest payments, especially when it comes to using taxpayer dollars to fund methane digesters and manure lagoons to offset the horrendous environmental and health impacts of CAFOs. In fact, the 2002, 2008, and 2014 Farm Bills actually mandated that 60% of the EQIP budget be allocated to animal agriculture operators with the biggest potential for environmental remediation. These operations are eligible for 70% cost coverage up to $450,000 per owner, an egregious comparison to the cap of $20,000 annually or $80,000 over any six-year period for organic production projects. This expansion just so happened to coincide with the expansion of the Clean Water Act to address CAFO pollution issues – a perfect example of agribusiness lobbies essentially writing legislation for their own benefit.

Despite attempts to return to free market agriculture with the 1996 Farm Bill (“Freedom to Farm”) which decoupled subsidies from specific crops, eliminated the previous set-aside acreage requirements, and shut down the strategic grain reserve, unforseen conditions led to large yields, which led to oversaturated markets. From this failed phasing out of subsidies on, the 2002 Farm Bill made disaster bailouts into normal budget items, and the decoupled payments into permanent direct payments. Although this Farm Bill also promised record spending on conservation programs, appropriations gutted the funds, and four out of five applicants to the programs were turned down. Although automatic payments were eliminated in the 2014 Farm Bill, about 60% of farmers’ insurance premiums, and some claim-related losses, are still taxpayer-funded. Environmentalists and other critics say that prevented plantings payments and other insurance programs incentivize risk in marginal lands, like planting in seasonal wetlands in spring.

What could agriculture look like with far fewer subsidies and direct payments? What could agriculture look like if subsidies were primarily used as a tool to incentivize diversification and the adoption of landscape-scale conservation practices?

The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide, pg. 106

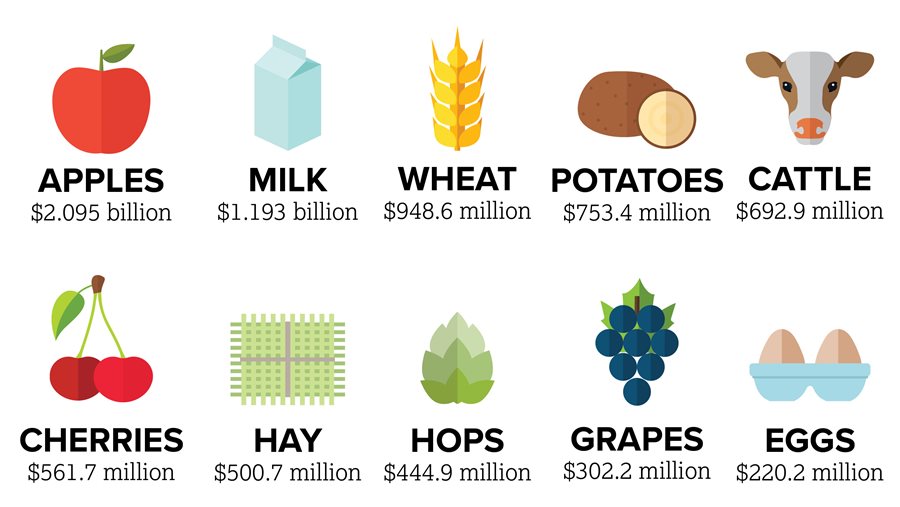

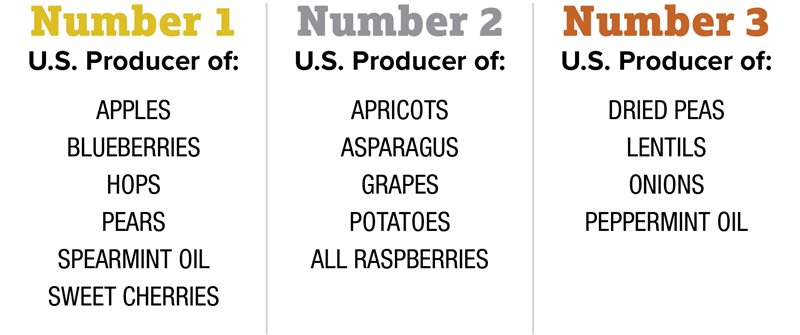

The U.S. agricultural subsidy game is strongly stacked towards commodity crops, leaving out states like Washington, which is the top “specialty crop” producing state after California and Florida but only received 1.5% of total subsidies for produce in 2014. Imhoff states that “it’s often more important to to know who ultimately benefits from policies rather than who gets the money directly” (pg. 81), and from this perspective it becomes clearer that current subsidy policies, which essentially have no payment caps due to legal loopholes and lax enforcement, mainly benefit CAFO operators, corporate mega-farms, input suppliers, and big grain traders.

Policy reform needs to focus on increasing financial and geographical access to in-season fruits and vegetables for consumers, help small farm operations earn fair prices, rewards environmental stewardship, and incentivizes resilient and regenerative farming methods – essentially a Farm Bill that prioritizes holistic community well-being with a vision further into the future. We can fight to realign subsidy programs with public health outcomes, stop EQIP dollars from being allocated for waste management at CAFOs (or any subsidization without social obligation), invest in energy efficiency and integrated energy solutions instead of continuing to double down on corn ethanol production, increase funding for conservation programs and fight to keep their spending off the chopping block during appropriations, add Climate Change, Labor, Urban Agriculture, Animal Husbandry, and Food Waste Reduction titles to the Farm Bill, and invest in shortening food supply chains with infrastructure development (i.e. processing and slaughter facilities, distribution hubs) in local food systems.

One of the biggest challenges to understanding the Farm Bill is its incredible reach and frequent changes. However, that omnibus status also makes it an unusually strong opportunity for organic farmers, sustainable food and ag advocates, and social activists of all types to regularly lobby and organize to promote the necessary wide-ranging reforms for a more resilient and regenerative U.S. food system.

Tuesday 5/24 & Wednesday 5/25

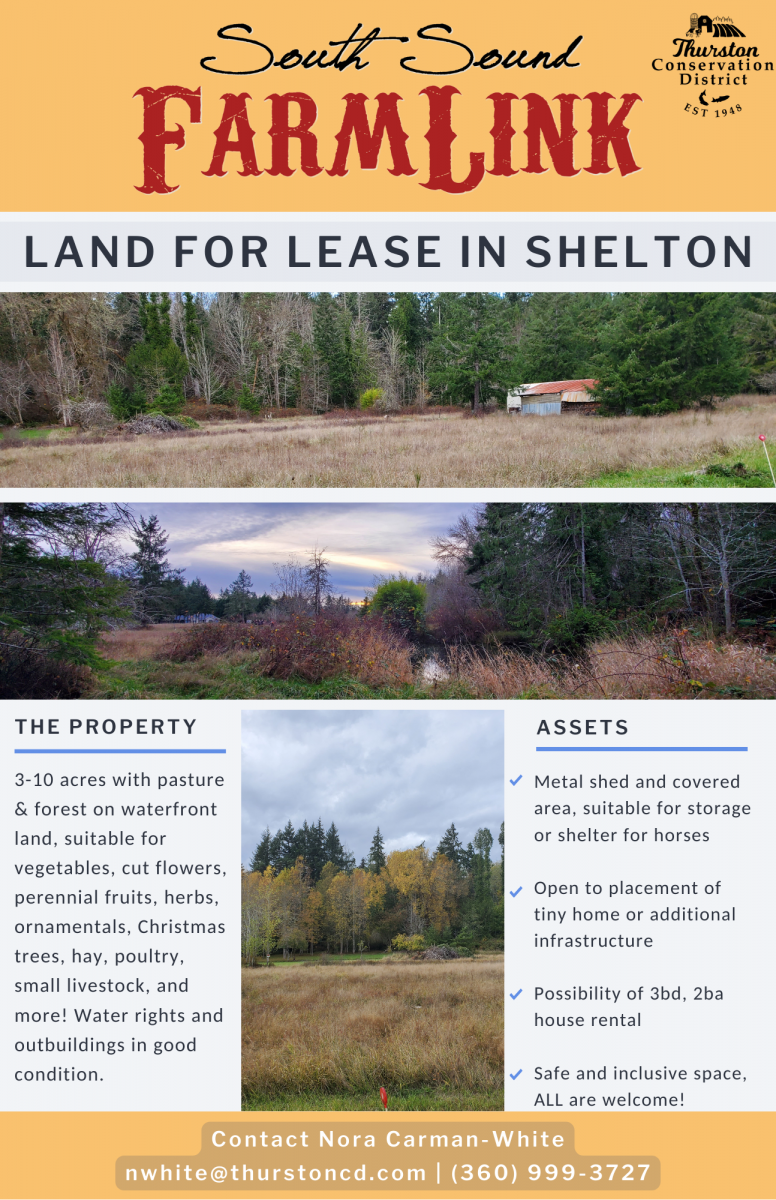

My biggest focus for the week has been making FarmLink land listing flyers. I modeled them off of a real estate flyer template, but it’s a bit more difficult to make one consistent template for land listings themselves with such a diversity of available land offered for lease through the program. I at least was able to set a general color scheme and layout, with flexibility for the different types of operations. Photos and information were provided by the landowners themselves, and I made sure not to include addresses or other potentially indentifying information. This was a bit more difficult with the flyer I made for the pasture listing, as I used Thurston GeoData Center’s Property Map and Information lookup to create a quick aerial overview of the available parcels, but without adjacent road information or including neighboring land.

I also found it challenging to prioritize broadly relevant information in short blurbs for some of the listings – how can I summarize what’s most important to both the landowner and what might be important for a landseeker? Consulting with Nora about additional background about each landowner, the land itself, and thinking overall about the landseeker information I’ve seen in the database emphasized how personal of a decision it is on both sides of the potential match. Some landowners seem fairly hands-off or flexible – they simply want their unused or underutilized property to have a good steward. Others were more specific in their wishes – one specifically hoped that a potential leasee would be interested in using the land as a community garden, and one firmly specified “NO BIGOTS ALLOWED”.

One of the biggest recurring themes I saw in working on the FarmLink program is that landseekers overwhelmingly wish to live on the land and either outright buy or have a lease-to-buy arrangement. Many have farmwork or farm operation experience, and submitted business plans along with their application. Others are a bit too idealist and are unfortunately, unlikely to find a match (hence the reworking of the application into a ideal/acceptable/dealbreaker framework). Few land listings have housing available or possible on site, and if so, often in the form of allowing a trailer/camper/RV. Perhaps once more matches are made, stronger relationships between leasors and lessees are established, and the program gains momentum, more workable arrangements can be found. Land transfer is not a simple or impersonal matter, but I have hope that beginning farmers and landowners in the South Sound can start working together more closely for the future of our region’s agricultural lands.

Thursday 5/26

I had originally planned to table with Kiana at the Olympia Farmer’s Market tomorrow morning, but different plans came up since tomorrow is also my 30th birthday! Fortunately she was completely understanding, and one of the field crew interns will join her at the market. I’m a bit disappointed I have to miss out, but I’m also looking forward to having a short break from school and work to celebrate what everyone keeps telling me is a milestone birthday. Today, as I have several times before, I packed up and printed out everything necessary for tomorrow’s tabling event and put it together so it’s easy to grab and go. It can take longer than you’d think, especially when the printer acts up and there are one or two tables, some chairs, a canopy, or other heavy/awkward supplies needed.

I also took the time to interview on Zoom for an AmeriCorps Food Educator position located in Bellingham. The non-profit farm organization sent me interview questions ahead of time, which was a nice touch which helped me feel more prepared and confident during the interview. I’m still concerned about the feasibility of affording living costs with the living stipend, but I’ve been creative enough to survive off that amount before, and the opportunity would be a fantastic one. Either way, I’m glad I had the opportunity to interview, and we will see if they invite me to continue the application process.

Bibliography

Imhoff, D., & Badaracco, C. (2019). The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide (3rd ed.). Island Press.

National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. (2018, January 9). The Farm Bill- From Seed to Plate [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SHGad3uzV0c&feature=youtu.be

The Farming Problem. (2022). U.S. History. https://www.ushistory.org/us/49c.asp

Thurston County. (2022). Thurston GeoData Center – Property Lookup. Thurston GeoData Center. https://www.geodata.org/quick-parcel-search.html