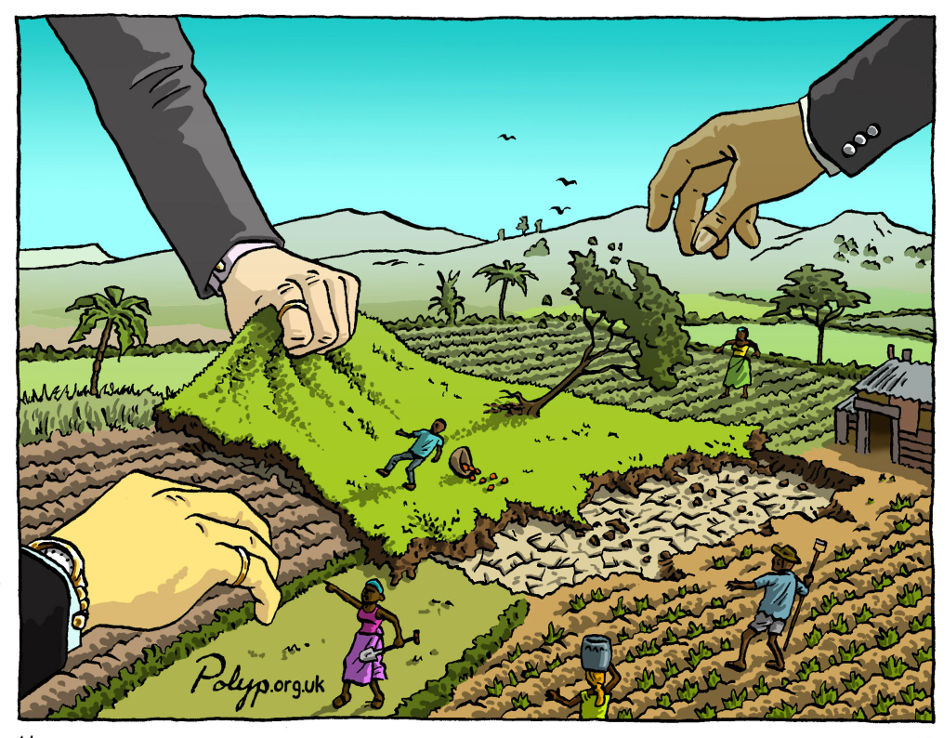

The entire history of colonialism and its post-colonial consequences have played a major role in shaping landscapes, from the creation of large mining complexes to the destruction of vast stretches of forest, to the creation of plantations and the displacement of indigenous people onto marginal and fragile lands. The enormous waste of war has been integral to the process as well. The point here is not to take sides or to make retroactive moral judgements about all the implications of these events. Rather, it is to insist that conservationists recognize that their work is ultimately governed by massive shifts in power and interests that they cannot control but must attempt to understand if their work is to endure. Conservationism without political and historical consciousness cannot hope to be well designed or well positioned.

“Nature’s Matrix”, pg. 85

Did I say last week that I was glad I read Nature’s Matrix later in the quarter? I revisit and challenge that previous claim after finishing the second half of the book with the mental exhaustion of someone revising her final academic statement while working ~30 hours a week on top of this capstone experience and 4 credits of research in the Aquatic Ecology Lab. Honestly, though, despite the density and cross-disciplinary breadth of this book, it has opened many new channels of thought and almost makes me wish I had a few more weeks to weave together the threads of inquiry into rural development, nature resource management, conservation biology, and political ecology I’ve been spinning this quarter. My biggest critique is perhaps that the main arguments become somewhat belabored, but the ultimate message is a vital one that perhaps needs to be driven home repeatedly for the intended audience — conservationists, especially those working in tropical bioregions, must be fully informed of historical and political context in the landscapes they work in, and must consider poor rural farmers as their greatest allies in the fight to protect biodiversity. Nature’s Matrix is also an interesting contrast to Farm (and Other F Words) not only in the geographical scope, but that it makes many similar arguments about disastrous impacts of U.S.-driven rural development policy and the power of grassroots social movements, along with calls for solidarity with the most disenfranchised farmers and agrarian reform.

While emphasizing once again that “the planet was not a clean slate upon which Europe wrote the world’s destiny” (pg. 81), the authors outline how European colonialism harmed the diverse biological systems, including environments and peoples, in the New World through the introduction of domesticated grazing animals (with the exception of llamas and alpacas in the Andes, which had long ago been domesticated by indigenous populations), the plough, disruptions of traditions and governance, and new technological and organizational machineries driven by greed. These new forms of governance across the globe included direct colonial government, private enterprises, treaties, formal, and informal arrangements; often, in succession as in India the British East India Company’s direct governing power was replaced by the British government’s direct colonial rule.

This legacy continued as World War II drew to a close and the Bretton Woods institutions (the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund) were created to promote economic recovery and stability in industrial nations. The pivot from post-war reconstruction to Cold War foreign policy implementation was swift as the US used these institutions, alongside others, as counter-measures against the threat of communism and socialism in the Third World (poorer nations which were neither First World industrial capitalist nor Second World communist). By the 1950’s, the IMF’s general strategy was to intervene in Third World economic crises by offering bail-out loans to stabilize currencies with the condition of accepting massive deflation, simultaneously implementing “Structural Adjustment Programs” (SAPs). The World Bank worked closely with these IMF programs to finance infrastructure investments, attempting wherever it could to use public financing to leverage larger amounts in private capital. Ultimately, the outcome of these interventions relevant to the discussion here was making raw material and agricultural exports available at much cheaper prices to other nations by reducing regulatory pressure on investors, reducing tariffs and other trade barriers, opening mines and running them at full capacity and speed, clearing forests, and converting farmland from local food production to commodity production for foreign markets.

After the Cold War, the justification for and implementation of these foreign policies shifted towards putting more emphasis on eliminating trade barriers, often styled the Washington Consensus. The World Trade Organization (WTO), which carries forward much of the neoliberal program which encourages economic growth without government regulation of business practices or policies to support “public interest” activities, has faced the strongest opposition from environmentalists, labor groups, and small farmer organizations which have suffered the most from these agricultural policies.

The underlying dynamics of expansionist capitalism combined with the specific programmes for growth and development adopted by the ruling powers after World War II would seem to constitute a reasonable foundation for understanding both the ever more rapid use of the world’s resources and the relentless concentration of their use by a minority of the world’s population. Careless habitat degradation and the decline of biodiversity follow the same logic. The problems in a sense are not accidental consequences of economic growth but are the accepted price of a well-developed overarching policy.

pg. 91

Much as the central thesis of The Farm as Natural Habitat is a refusal to accept agricultural lands in the US as an “ecological sacrifice zone” where harmful environmental practices must be concentrated to save the remaining “wild areas”, Nature’s Matrix also recognizes the inherent connection between human welfare and biodiversity conservation on a more global scale, just as it recognizes connections between economic policy and environmental degradation.

Much of the rest of the book is a deep dive into the struggle over the Amazon Rainforest in Brazil, detailing the complex historical, political, and social realities which have lead to poor rural populations either intentionally or unintentionally clearing the way for corporate development and deforestation in the Amazon by being offered land and incentives to cultivate its frontier. The details of the struggles and strategies of Direct Action Land Reform in Brazil, most notably the Landless Workers Movement or the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST), and the ways they have both clashed with and allied with conservationists in the Amazon is well worth reading, if incredibly difficult to summarize here.

(I learned more about the MST’s food sovereignty and land reform efforts through members’ direct viewpoints in an excellent article by Civil Eats: “Brazil’s Landless Workers Persist through Agroecology”.)

The authors use this case study to argue for forming positive links between conservation and the welfare of the poor — using agricultural techniques that preserve hard-won redistributed land, the necessity of democratization of rural countryside as well as national politics in rejecting destructive frontier development, and recognizing and rejecting sources of systematic bias in conservation practice.

One of the most notable of these biases, which is excellently addressed in socio-ecological terms as a misunderstanding of “competitive exclusion vs. overpopulation” (pg. 101), is the lingering implicit and explicit Malthusianism present in many conservationist circles. One of the most notable examples I’ve come across in the past is the Center for Biological Diversity’s Population and Sustainability program. While I certainly can’t condemn the aim of the organization’s work, especially regarding protection of endangered species and advocacy for reproductive justice (albeit one-sided) I’ve always been troubled by their framing of the “population problem”. For a local example, their website frames the “2001 extinction” of the Lake Sammamish kokanee salmon as a simple function of increasing fertility rates (as they seem to do for most species extinctions and habitat loss), rather than more deeply analyzing Seattle’s rapidly expanding urban growth area as a complex function of policy, city planning, and economic conditions, among other factors such as installation of undersized/impassable culverts and improper stormwater management. (Interestingly, Lake Sammamish kokanee are not actually extinct despite the Center for Biological Diversity’s claim, and although they’re still extremely endangered, recent efforts by the Kokanee Work Group partnership have restored the salmon to creeks they’d previously been extirpated from).

The authors of Nature’s Matrix take a much different approach towards addressing issues of personal agency and systematic change in biodiversity conservation and resource consumption by concluding that agro-ecological principles “are most likely to be enacted by small farmers with land titles — a product of grass roots social movements” (pg. 133). Rather than treating poor rural farmers, or even humans in general, as the enemy of the rest of biological life, they make a rigorous argument rooted in history, ecology, economics, and sociology that recognizes the fate of nature as the fate of the people who depend on it, and vice versa.

Over and over again throughout my studies, I find the point that regional context is essential to understanding the issue at hand. I look forward in the next two weeks to studying more local agricultural policy and history, and exploring food sovereignty and rural development efforts in the US, Washington State, and Thurston County.

Tuesday 5/17

“The District plans to use the site to:

• Support beginning farmers, including urban and backyard farmers, with education and resources with which to manage their farmland and agricultural businesses.

• Serve existing producers with resources and support to manage and develop their farm operations.

• Provide site-specific education opportunities with classes and workshops for children and adults.

• Operate as a ‘Conservation Hub’ where other partners may meet, network, work, host events, share resources, and collaborate. And to serve as a one-stop-shop for Thurston County producers.”

Most of today’s time at the office was spent in a staff meeting — this time over Zoom. I’d become quite spoiled by the other two staff meetings/site tours I’ve attended (one at Mt. Capra Goat Farm and the other at The Give Back Garden). After the meeting, I debriefed with Nora and Kiana a little about Prairie Appreciation Day. We realized that it was my last big event planned, and they asked me what my goals were for my final few weeks of the internship. We agreed to meet tomorrow more intentionally to discuss that question, so I spent the afternoon finishing up the Teens in Thurston logo and getting feedback from Sam. I wish I had the tools and skills to make a better quality version, but I think it will look great on a sweatshirt and on flyers for next year’s program!

TCD also just put out a Request for Proposals (RFP) for a property to accomodate a new Conservation & Education Center (CEC). This is a huge and exciting project, and I look forward to the CD finding a new home that’s much better suited to its new direction and the community.

Wednesday 5/18

This morning I sat down with Nora and Kiana to talk about goals, projects, and questions for the next two weeks. I like to finish what I started — on my personal to-do list I added “finish organizing the outreach and education shelves/aisles in the storeroom”. Most of the other things are social media or design related, like finishing two more wildfire awareness month posts, writing up something about TnT’s volunteer outing at Prairie Appreciation Day for next month’s TCD newsletter, and updating the TnT outreach materials for next school year. I was curious to learn more about about internal organizing and tracking (i.e. participation in Technical Assistance/Voluntary Stewardship) so I got to see more Smartsheet functionality than I’d already been introduced to (the outreach/education dashboard tracks volunteers and event attendees, for example).

One of the two lingering big projects that I’ll focus on are making a land listing template for FarmLink – kind of a real estate flyer style preview with photos of and essential facts about available land for those seeking it. In addition to the template, I’ll actually draw up flyers for the land owners actively enrolled in the program at this time. Hopefully this will be a more effective tool for making matches.

We also sat down and brainstormed about creating a new website map proposal that fits with the 5-year Strategic Plan and the board’s input on website focus/resources. We looked at other Washington conservation district websites, including Whatcom CD’s recently re-designed site, to get a better sense of what works well and what doesn’t. There are a few pages in particular that have by far the highest number of traffic- namely the soil testing and equipment rental information pages.

Finally, I finished up a wildfire awareness social media post about outdoor burning rules. I may need to make some small edits, but I think I’m starting to get the hang of this design thing! Canva makes it quite fun and straight-forward, but it takes more time than I would’ve thought to make something I feel good about sharing.

Thursday 5/19

I got final approval from Sam on the TnT logo today, and I sent him some simple mock-ups of black and white versions of the logo on different colored backgrounds to help make the decision of what to order for the sweatshirts. Nora and I both personally voted for dark green sweatshirts with a white logo, but we’ll see what he decides! Most importantly, I hope all the volunteers like the design. If we’d had more time, I would’ve liked to come up with a few different versions and have them vote on their favorite. I also finished a TnT outreach flyer for next school year, modifying the design from last year’s outreach flyer and adding a photo of volunteers from a recent event as well as the new logo.

Side celebration: today I saw my name listed on Evergreen’s graduation page on the website. I appreciate being first in alphabetical order if for no other reason than getting a nice screenshot! I’m still amazed that I’m so close to accomplishing this degree, and grateful for all the support and guidance along the way. It feels unreal still that I not only am graduating from college, but did the majority of it during a global pandemic and managed to have several internship experiences, a capstone scientific research project, help start a co-curricular community garden on campus, and make a few friends along the way. Although the immediate future is uncertain, I’ll have a degree — and celebrating that is enough for now!

Bibliography

Center for Biological Diversity. (2022). Tackling the Population Problem. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/population_and_sustainability/population/

Forsetto, R. (2020, October 7). Brazil’s Landless Workers Persist through Agroecology. Civil Eats. https://civileats.com/2020/09/30/brazils-landless-workers-persist-through-agroecology/

La Via Campesina. (n.d.). La Via Campesina | International Peasants’ Movement. Via Campesina English. https://viacampesina.org/en/

Perfecto, I., Vandermeer, J., & Wright, A. (2019). Nature’s Matrix: Linking Agriculture, Biodiversity Conservation and Food Sovereignty (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Wilson, C. (2021, December 1). Kokanee salmon make a comeback in Zackuse Creek. Issaquah Reporter. https://www.issaquahreporter.com/news/kokanee-salmon-make-a-comeback-in-zackuse-creek/