This story fits well into the organic mythology in the morals that it offers: respect for the natural order as revealed particularly by the wilderness brings economic growth to those who are not fixated on short-term gains; true science goes out from the laboratory and studies the ecological context, observing rather than trying to dominate; variety is more productive than monoculture; industrial products bring disease and waste.

Philip Conford, “The Origins of the Organic Movement”

I started this week feeling exhausted, depressed, and all but completely burned out–physically and mentally. I’m closing my third year at Evergreen, about to graduate with my dual Bachelor’s in Science and Arts, and still feel as if I haven’t done enough or been able to accomplish all I wanted to while here. Despite this amazing experience as a community outreach intern, having two jobs including one that’s public-facing on campus, and doing research in Carri’s lab this quarter alone, I feel as if I should somehow stretch my hours supernaturally to help with the community garden more, to get involved with SCARF, invest my time into helping rebuild a vibrant campus for next year’s students and beyond. At the same time I can’t help but mourn my lost opportunities, having gone back to college in Fall 2019 with no idea what was to come. I remember last year in Terroir/Meroir, there was a day when we ended up discussing Saturn returns, so here I am two weeks shy of my 30th birthday in the throes of it. My own hangups around interpersonal connection and physical ailments aside, I must refuse despair and be proud of myself, my fellow students and colleagues, and all that we’ve accomplished despite the odds. The point is to carry what I’ve learned at Evergreen forward to my next steps. I feel hopeful and resolved when I remind myself of who I am and the people who’ve helped me get here.

This week I read the first half of Nature’s Matrix by Ivette Perfecto, John Vandermeer, and Angus Wright, and it helped me synthesize much of what I’ve learned in my classes the last three years. The book is written more for an academic and scientific audience than any of my other readings this quarter (with the possible exception of some chapters in The Farm as Natural Habitat), but I was pleasantly surprised and challenged by its contents. It primarily focuses on the tropics (especially in Central and South America), which provides a broader social and geopolitical context to conservation and agriculture. An argument is quickly established: agroecosystems are an important part of the natural world and biodiversity conservation. Whether these systems are beneficial or detrimental depends on the type of agricultural production, which is also a determinant of what kind of biodiversity the ecosystem contains.

To understand the particulars of the authors’ ecological argument, an understanding of the metapopulation theory (a “population of populations”) is necessary. Appropriately for synthesizing my Evergreen educational journey, I took a program called Ecological Dynamics in spring 2020, which focused on population ecology and quantitative methods for analyzing metapopulations, equilibrium theory of island geography, and source-sink dynamics. All are relevant here, but essentially, metapopulation theory states that a species will become totally extinct in a fragmented habitat once immigration or colonization rates fall below the death or emigration rates. If we consider salamanders, for example, animals whose migratory routes are frequently made impassable by roads, they may disappear entirely from a landscape if their ability to travel between suitable habitats (one patch of water to another) is interrupted to the point they’re unable to escape destroyed habitat and reproduce sufficiently to replace those animals lost. This of course applies to plants as well, depending on their ability to disperse. When thinking of a landscape mosaic, the habitat patches that make up a region, we should consider that local extinction rates are a function of the patch size. The basic question we should ask is “What is the probability of migration from fragment to fragment?”

Therefore, the basic idea presented in Nature’s Matrix is that while local extinction is an important force in evolutionary dynamics, and therefore frustrating if not impossible to completely avoid in conservation projects, it is more effective and actionable to protect populations’ migration potential between patches of suitable, high-quality habitat, reducing regional and global extinctions. This is where the type of agricultural production in each cultivated patch becomes crucial, necessitating conservationists to examine the socio-political aspects of this “agricultural matrix”.

Chapter 3 of Nature’s Matrix ambitiously summarizes the history of modern agriculture from traditional migratory “slash and burn” farming that operates on production-fallow cycles, which depend heavily on land tenure arrangements (being able to return to a previously cultivated piece of land which has lain fallow for several years). These methods, while specific to region and culture, share many characteristics, including being steeped in tradition, yet flexible and innovative. The rise of modern agriculture began during European settlement of the Americas–as discussed a few weeks ago when I read Farm and Other F Words by Sarah K. Mock. This transformation of land use and economy in Europe was driven by a demand to produce more food on less land with less labor, and American plantations formed models for this new economic enterprise.

An incredibly interesting observation made in the book is that a major cornerstone of European domination of the world economy was the acquistion of soil fertility by seizing new territory. The authors posit that this wealth of productive fertile soils was just as, if not more important to European accumulation of wealth than other natural resources or precious minerals. The dominance of the industrial agricultural model took off after World War II — despite the Great Depression, caused at least in part by a crisis of overproduction — and alongside the burgeoning synthetic fertilizer industry, chemical pesticides emerged on the marketplace, a war metaphor replacing a health metaphor for pest management on the farm. Globally, the Green Revolution offered technological “solutions” to impoverished countries’ social, economic, and political problems of hunger. As is an incredibly frequent pattern throughout world history, the Green Revolution’s export of industrial agricultural production was largely driven by the fear of land reform and wealth redistribution. A divide between the practice of farming and the business of agriculture was made.

A major point to state right away is that increased management intensification on a landscape is negatively associated with biodiversity. Within the modernized agribusiness model, the broad goals are more frequent use of the same area of land (decreasing the time of fallow periods) and increased specialization of productive species (resulting in loss of plant biodiversity, usually in pursuit of higher yields and ease of mechanization). Further complicating matters is the “pesticide treadmill” mechanism outlined in the 1978 book The Pesticide Conspiracy by Robert Van Den Bosch, where after pesticide application, there’s a resurgence of pests, which then evolve resistance to pesticides, resulting in more application, and a secondary pest outbreak. The authors of Nature’s Matrix posit a similar “fertilizer treadmill” mechanism as normal nutrient cycling in soils is disrupted through repeated artificial input of synthetic fertilizers.

Moving on to alternative methods of production which could offer conservation solutions and protect the landscape matrix, the authors outline three major models from which to draw: 1) traditional/Indigenous agroecosystems, 2) extant organic farms within a larger landscape of conventional/industrial farms, and 3) “natural systems” agriculture which is based on ecological dynamics of local ecosystems. In analyzing the benefits, drawbacks, and specificities of each, they are careful to emphasize that any applications to modern systems from traditional models should be localized and site-specific. They also point out that not all traditional agroecosystems are or were sustainable, avoiding tropes of over-simplification or ahistorical analysis of Indigenous culture and practices. They also have excellent reflections on the power and importance of equal partnerships between ecologists and traditional farmers, highlighting Cuba’s transition from industrial to sustainable agriculture after the collapse of the Soviet Union as a model. As for organic farming, the authors analyze the potential of organic agricultural yields matching those of industrial yields, but treat with caution the tendency of growth and consolidation creeping into the organic sector. As they also point out earlier in the chapter, the biggest barrier to transitioning to any of these models is operating within the political and economic assumptions that come along with the dominant social form — commodity production within modern capitalism.

I honestly can’t believe these are only the first three chapters of a six-chapter book! I’m glad that I saved it for later in the quarter, because other books were able to give a broader context for the incredible span of disciplines and amount of dense information packed in Nature’s Matrix. I’m appreciating the more global view of agricultural production, and how I’m being challenged by rigorous cross-disciplinary academic arguments and insightful observations on both rural development and conservation biology. The next chapters are more socially focused and contain case studies in the tropics, and I look forward to diving into them for next week.

Tuesday 5/10 & Wednesday 5/11

This week was fairly slow, as Kiana was working remotely and Nora took a day off for sheep shearing. I did final prep for Prairie Appreciation Day by confirming details with Angela, ordering lunch for pickup, coordinating with Sam and Nora, and also helped out Kiana (who will be tabling for TCD, separately from our TnT event) by packing up everything she needs (canopy, table, displays, handouts, pens, etc.) and printing/cutting out some postcards for Plant Sale pre-order notifications. This reminded me that another big project I’d like to at least make a dent in before the end of the quarter is cleaning and organizing the education and outreach areas of the storeroom. I made some good progress getting rid of outdated materials and organizing the ones left at the beginning of the quarter, but there’s been a few events since, and both very large and very small items are still kind of strewn everywhere.

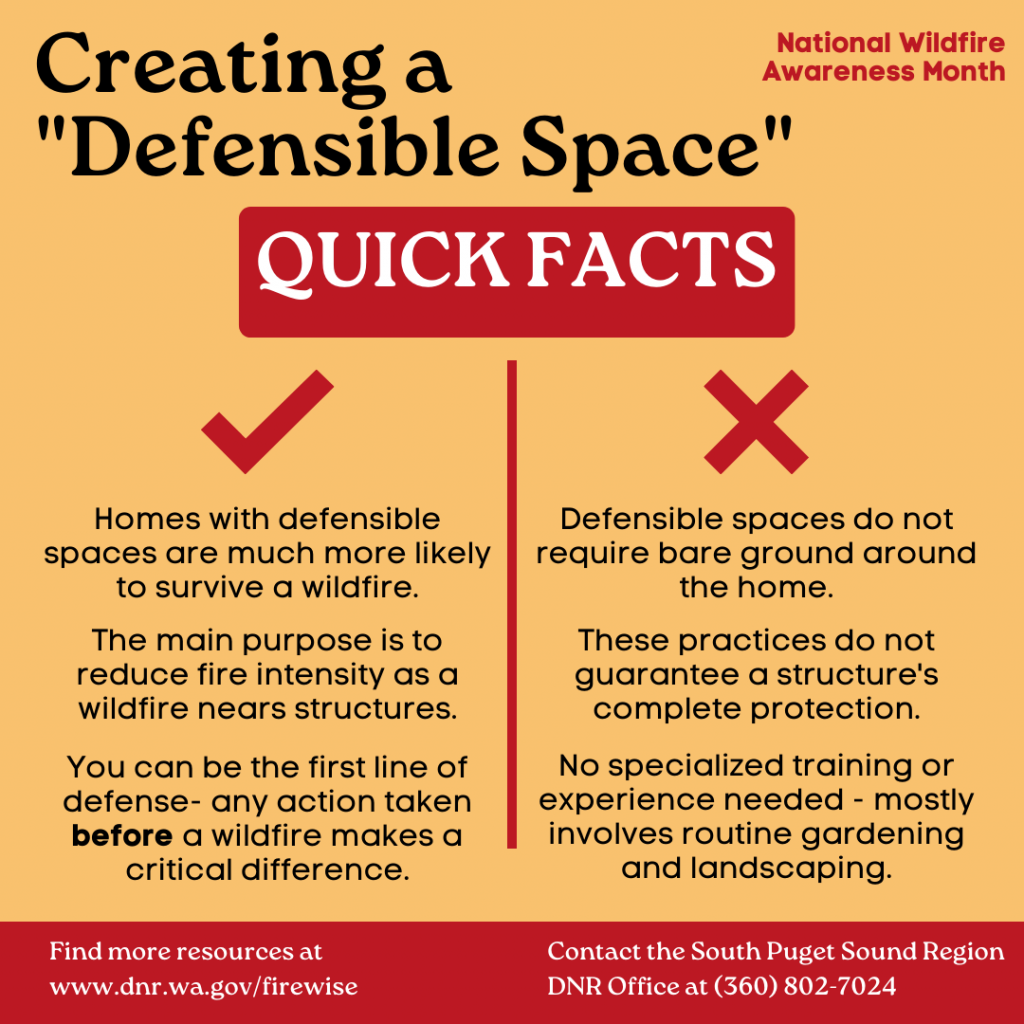

My other project is working on a series of social media posts for National Wildfire Awareness Month using materials from the Washington State Department of Natural Resources’ Firewise USA guide. This is my first one, and I’m planning to make one about outdoor burning rules/wildfire prevention and another about wildfire preparedness with livestock. Turns out that designing is quite fun!

Thursday 5/12

Today I was invited to an interview for an AmeriCorps Food Educator position with Common Threads Farm in Bellingham! I’d nearly forgotten about my application in the hectic pace of the last few weeks, so it was a pleasant “surprise”. There are three positions available, and I’m most interested in the Community-Based Food Educator one, which primarily leads after-school and school break programs that involve gardening and/or cooking with kids of all ages at community gardens and affordable housing complexes. To be honest, I have mixed feelings about serving in AmeriCorps for a year vs. finding work with full pay and benefits. However, this would be a wonderfully fulfilling opportunity to give back to a community where I once experienced hunger myself.

Saturday 5/14

Prairie Appreciation Day was a great success! While only three TnT volunteers attended, they were a lot of fun to hang out with and we enjoyed some warm sunny weather (in contrast to the cold, rainy, windy forecast). Angela, the volunteer coordinator at CNLM, was kind enough to give us all a short walking tour of Glacial Heritage Preserve and talk about the restoration history of the land. The TnT volunteers had great questions and it was fascinating to see and learn about an area of Salish Sea prairie that I’d never visited before. While reading Nature’s Matrix this week and revisiting what I learned in the Ecological Dynamics program spring 2020, which immediately followed my restoration ecology internship at JBLM during winter 2020, I thought often of the fragmented South Sound prairies and the lack of habitat connectivity between them. This is perhaps why Taylor’s checkerspot butterfly is locally extinct at Glacial Heritage despite such successful habitat restoration efforts — there’s no immigration as the next nearest population would have to cross what amounts to a barren wasteland, for them. This prairie is nothing short of a restoration triumph, however, as Angela told us 25 years ago, nearly the entire preserve was a thicket of five-foot-tall scotch broom. As you can see, it’s now a breathtaking landscape of prairie flowers. If you’re interested in reading more about Camas prairies, you can check out my Week 5 post.

Addie, RiRi, Leila, Nora, Sam, and I spent a few hours pulling scotch broom (very small ones!) at a site that hasn’t been burned yet. It was nice to chat with the volunteers and get to know them a little bit better, as I’d met them a few times at previous events. They’re all juniors at Olympia High School, I was impressed by how informed about and involved in political and environmental issues they all are. They told us that they’re excited for next year’s TnT events and are trying to get a lot of their friends to join as well. I got to chat with them a bit more about Camas cultivation which was a fun opportunity to pass along what I’ve been researching and learning about. After broom pulling, we enjoyed some pizza for lunch while sitting in the grass near CNLM’s buildings, then parted ways to check out the different booths set up around the preserve before the kids’ parents came to pick them up.

Before I left with Sam, I got to talk with a few different folks — I ran into Carissa, the sheep farmer I met a few weeks ago at the Violet Prairie Plant ID walk, who also works for Ecostudies Institute, and also saw Paris, one of my research group partners from the last two quarters, plus Ashley Lewis and Sarah Williams! I was grateful for the opportunity to connect and reconnect, introduce Sarah to Kiana and Sam, and be a part of teaching others about the beauty of Salish Sea Prairies.

Bibliography

Dee, R. (2008). Conservation Buffers – Biodiversity. USDA National Agroforestry Center. https://www.fs.usda.gov/nac/buffers/guidelines/2_biodiversity/introduction.html

Perfecto, I., Vandermeer, J., & Wright, A. (2019). Nature’s Matrix: Linking Agriculture, Biodiversity Conservation and Food Sovereignty (2nd ed.). Routledge.