The evidence of a strong tradition of collective farming that has succeeded socially and economically in America, particularly as organized by communities of color, is incredibly hopeful… Independent family farms have overwhelmingly proved themselves incapable of meeting the challenges of the past, let alone those of a hotter, dryer, and much less certain future. But collective-farm alternatives offer a blueprint to something fundamentally different, not a small family farm, but a big team farm.

Sarah K. Mock, “Farm (and Other F Words)”, pg. 208-209

I want to start this week with intention. Nearly halfway through the quarter, I’m learning a lot about the ins and outs of daily outreach work and event planning, but I also feel the looming fact that my time at TCD, and Evergreen, is coming to a close very soon. A few weeks in, I realize that 1) I want to get involved with South Sound FarmLink, and 2) learn more about the grant writing process, especially for Voluntary Stewardship Program technical projects. In my work with the district and in conversations with friends these seem to be some of the major issues in our region (and likely beyond): 1) it’s almost impossible to find and secure land to begin farming on if you’re not already wealthy, and 2) for those that already have land and desire to improve their stewardship of it, they may need help obtaining available money for improvements.

I read The Uncommon Knowledge of Elinor Ostrom by Erik Nordman this week, which I’m glad I read before diving into the dense but essential source Governing The Commons by Elinor Ostrom. Nordman’s book weaves together Ostrom’s biography and her research on the political economy of common-pool resources–showing that regular people have figured out ways to sustainably self-manage commons without the intervention of the market or the state. Nordman also includes examples of expansion on her theories by colleagues and the work of some of her collaborators. Ultimately the book’s focus is on what lessons we can learn from her design principles (included below) when tackling some of the biggest resource management issues of the 21st century.

Ostrom’s Eight Design Principles for Managing a Commons

(Nordman, pg. 65)

- The physical and social boundaries are clearly defined.

- Locally tailored rules define resource access and consumption.

- Individuals who are most affected by the rules can participate in rule making.

- Resource monitors are accountable to resource users.

- Graduated penalties can be imposed on rule breakers.

- Conflict management institutions are accessible.

- Authorities recognize a right to self-organize.

- Complex systems are organized into layers of nested governance.

This excellent book helped me step back and reframe my thinking around natural resource management, the idea of a commons and democratic governance, interdisciplinary collaboration in research, and community problem-solving more generally. Most pertinent to my learning this quarter were Chapters 5 “Institutions for Collaborative Forest Management” and 7 “Voluntary Environmental Programs”. Reading about the influence of Dr. Margaret A. McKean’s research, specifically her 1982 conference paper The Japanese Experience with Scarcity: Management of Traditional Common Lands, on Ostrom’s work and their resulting collaboration, was thrilling. Studying iriai (“common access” lands) and agricultural practices on satoyama landscapes last spring was one of the most intriguing parts of my “Chain Reactions” ILC, and I’m glad to see my interest come full circle in a way.

Some basic definitions and ideas I took away:

- The technical definition of a common-pool resource is a resource which is subtractable and non-exclusive.

- An institution is the set of formal and informal rules developed by a community to govern commons.

- Ownership in a commons is defined by the rights to access a resource, i.e. the rights to access an area or harvest a material such as firewood. The strength of these rights is also called “tenure”.

- There is no “one size fits all” solution for successful common-pool resource management.

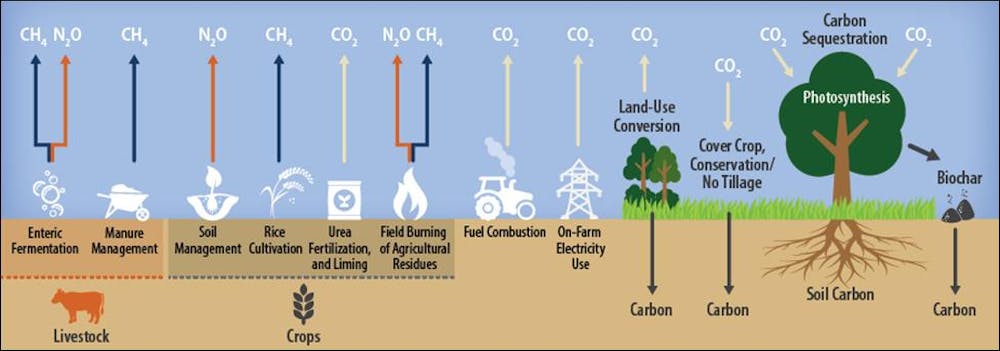

Now back to Sarah K. Mock’s book. Chapter 7, in which she (as I wrote last week) highlights the similarities between commonly-held lands in pre-Columbian North America and those in Europe prior to The Enclosure Acts, also summarizes Lin Ostrom’s challenges to The Tragedy of the Commons: “the idea that when a resource is held collectively, rational economic actors will inevitably arrive at the conclusion that whatever you don’t use, someone else will, so you might as well use as much as you can, for as long as you can” (pg. 177). Mock also points out that the argument that private property rights are needed to “protect” natural resources is also a post-facto justification for the violent dispossesion of Indigenous and African people, cordoning off the American commons for personal gain. Chapter 8 outlines a history we all should’ve learned from the beginning, that of the first farmers on this continent. While generalizing the hundreds, if not thousands, of Indigenous cultures and groups is inaccurate and ahistorical, the European and Euro-American efforts to wipe out these cultures and their histories leaves us in the present with an incomplete picture. However, it is clear from Indigenous histories, research, and the accounts of early settlers themselves, that broad similarities regarding tribal property and land tenure exist. Almost universally, collective management of land commons, mostly in proto-agricultural production (i.e. prescribed burning of prairies to cultivate wild food sources), was practiced. However, consistent with what I’ve learned from Ostrom’s design principles, language, climate, geography, and circumstances gave rise to myriad different institutions within tribes which regulated land and resource use. Diverse food sources, geographically-appropriate cultivation systems, and production of surplus food and fiber for trade and storage made for resilient, abundant food systems.

Following in the footsteps of these original “American” farmers, other marginalized communities have a strong tradition of collective farming. Citing a multitude of examples from Monica M. White’s Freedom Farmers (2018), Mock briefly tells the stories of Black communities in America using food and farming both as a means of resistance and survival. She rightly points out that “When Europeans forcibly brought enslaved Africans to America, it represented the first arrival of highly skilled farmers from across the sea” (pg. 195). My own attempt to summarize Mock’s summary will be reductive and inadequate, so I’m hoping to simply read White’s book for a fuller picture of organizations like the Colored Farmer’s Alliance (CFA) and Fannie Lou Hamer’s Freedom Farms Cooperate.

In the 1930s and again in the ‘60s, The National Resource Conservation Service came in and put in elk and deer-proof fences. They said you need to put fences around your fields so you can keep out all the animals that are going to eat your crops. My grandpa’s response was: “We’re farmers. When we plant corn, we don’t plant just for us, we plant for the environment around us too. If the deer are coming, it’s because they’re hungry. So, that means, I need to plant more.” We’re adjusting to our environment rather than trying to keep everything out. So, this idea of a fence is just antithetical to the way we view the world.

A-dae Romero-Briones (Cochiti/Kiowa), Director of Programs: Agriculture and Food Systems for the First Nations Development Institute, in an interview for Bioneers

Tuesday 4/19

This morning I got up extra early to help out with South Sound Regional Envirothon at Priest Point Park. Thurston CD coordinated the event along with Mason and Pierce Conservation Districts, and I got to talk to someone from Pacific CD who attended to see how the event was run and try to organize something like it next year. My main role was test proctor at the wildlife exam station, which I got to do with Yan, TCD’s accountant who volunteered for the event and I haven’t gotten to talk to much yet! It was really nice getting to talk with her while directing each team and grading all of their tests. The day was a bit of a blur as I helped with set up and tear down as well, but it went very smoothly and everyone seemed to have a great time. Stadium High School from Tacoma was the overall 1st place winner, but winners from each county are eligible for the state competition. I hope that some of the teams get to go and compete!

Wednesday 4/20

I worked on my ag plastic recycling project from home today, drafting a resource guide with what I’ve found so far. I included a photo of it above, without any of the contact information we’ll include later. I also reached out to Angela from CNLM to start planning for TnT’s participation in Prairie Appreciation Day on May 14th. While many of the activities are already planned, I need to get a better idea of the timeframe, plan transportation and lunches, find out what we need to bring, and make a flyer to send out to the group so they can RSVP.

Thursday 4/21

Today was a day of (relative) rest for me. I didn’t work on anything official for TCD as I spent extra hours this week on Envirothon and will be helping out with the TnT Earth Day event on Saturday. However earlier this week I connected with Alice from Thurston Climate Action Team’s Food and Agriculture Action Group to find out what they were working on, and tonight I attended the group’s monthly meeting. They’re mainly focusing on an outreach plan for composting education and modeling a curbside compost pickup proposal after Seattle’s program. Also they’re in the “waiting” phase of how to best support Haki Farmers Collective in a potential partnership with City of Lacey to develop a public food forest. Serendipitiously, Alice had connected with Nora a few months ago to talk about FarmLink and find ways to work together on an incentive program for young aspiring regenerative farmers, but that idea has been on the backburner for some time. I set up a time to talk on the phone with Alice next week and I’ll reconnect with Nora about it before then. What a lovely and surprising outcome!

In fact, a lot of things are falling into place for me this week–what I want to focus on not only in the remainder of this quarter, but beyond, into grad school and a career. The more I start conversations, see where I can help with good work being done in the community, and delve into both ugly truths and practical, hopeful solutions, I am finding my path and hopefully leaving things even just a little better than when I found them.

Saturday 4/23

For Earth Day, TnT went to Black Lake Meadows with Aimee from Pacific Shellfish Institute for a trash clean-up. It was a beautiful day and a solid group showed up for the event. We picked up an incredible amount of trash, especially in the wetland area (I’m glad that studying stream ecology for the last few years has made me always keep a pair of wading boots in my car). It reminded me of the last time I volunteered to clean up trash–there’s always a pleasant attitude in groups of people that choose to spend their free time collecting old chip bags and cigarette butts. We kept data sheets as well, which were hard to keep up with due to how much trash we found!

Bibliography

Mangan, A. (2021, November 10). Decolonizing Regenerative Agriculture: An Indigenous Perspective. Bioneers. https://bioneers.org/decolonizing-regenerative-agriculture-indigenous-perspective/

Mock, S. K. (2021). Farm (and Other F Words): The Rise and Fall of the Small Family Farm. New Degree Press.

Nordman, E. (2021). The Uncommon Knowledge of Elinor Ostrom: Essential Lessons for Collective Action. Island Press.

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Puget Sound Agrarian Commons. (2022, April 14). Agrarian Trust. https://www.agrariantrust.org/commons/puget-sound-washington-agrarian-commons/